by Sue Udry

National Lawyers Guild Review

Summer 2016

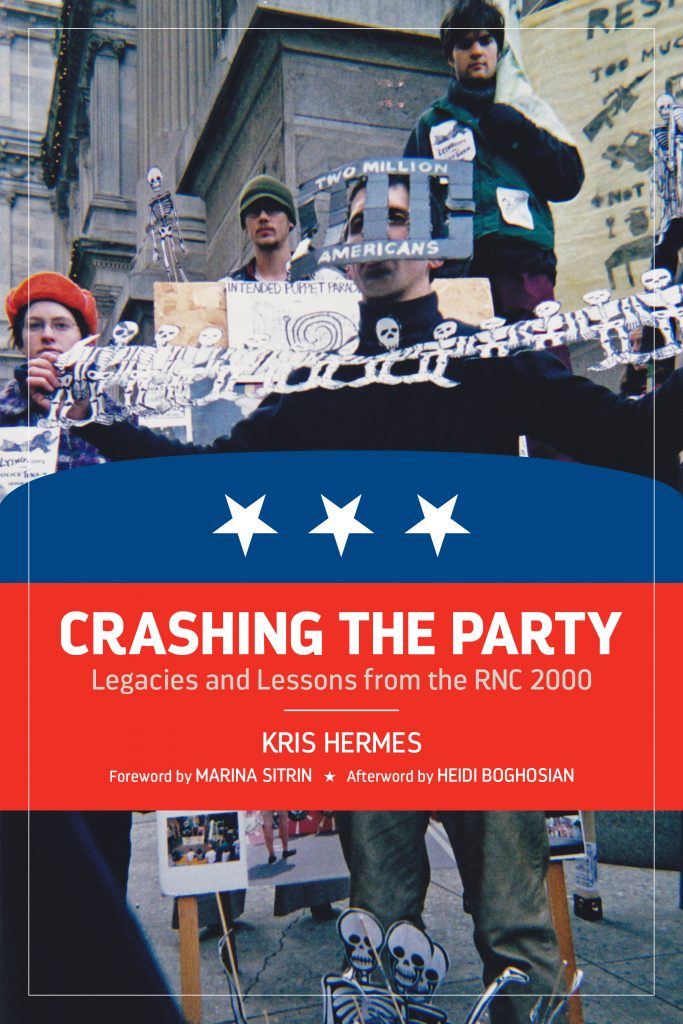

We knew exactly what would happen last July at the Republican and Democratic national conventions. City governments would make plans to restrict protests. Police departments would purchase riot gear, less-than lethal weapons, and other special equipment. Insurance policies would quietly be bought. Some assortment of federal, state and local police would in¿ltrate activist spaces, lurk on listserves, and stalk social media. In the mass media, a narrative would be crafted about dangerous protesters and outside agitators intent on crashing the parties.

Once the protests began, there would be agents

provocateur, mass arrests, preemptive arrests, false arrests, police

violence, abuse in jails, scapegoating of “ringleaders” and all manner

of repression. That’s exactly what happened at the RNC in Philadelphia

in 2000. Kris Hermes was there as a social justice activist and member

of the R2K legal collective. Hermes has written about his experience in Crashing the Party.

He documents how the people fought back using jail solidarity, court

solidarity, and democratically-run legal collectives that engaged

activists in the legal process to ensure political goals were not

subverted.

Hermes walks us through the events that

transpired—the preemptive raids, mass arrests, surveillance and

in¿ltration, aggressive prosecutions—and analyzes the ¿ghtback: What

worked, what didn’t, and why. What comes through most clearly is the

power of legal collectives to protect not only the rights of activists,

but their political goals and their desire to act in solidarity with

each other in opposition the state. Legal workers and legal collectives,

rather than lawyers primarily obligated to the best interest of their

individual clients, are best positioned to “empower activists to take

control of their own [collective] legal predicament.”1

August 1, 2000 was a day of action against the criminal justice system. Police responded to the protests with violence and mass arrests, and by the end of the day 420 people were in jail. While most of the arrestees were detained during the protests, 75 never even got the chance to exercise their First Amendment rights that day.

Sue Udry is a legal

worker member of the NLG, and serves on the board of the DC Chapter. She

is the executive director of the Bill of Rights Defense Committee/

Defending Dissent Foundation.

Preemptive raids on activist spaces are a favorite tool of the state because they allow it to smother the message in the cradle and minimize the impact of protests by feeding the “dangerous protester” narrative, depriving activists of art, Àyers, and other tools of dissent and locking some of the leading voices away from the streets at a crucial time. Using those metrics, authorities in Philadelphia hit one out of the park.

Almost two weeks before the protests began, the city raided and temporarily shut down the Spiral Q Puppet Theater using the authority of the Department of Licenses and Inspection. The raid disrupted workshops with single moms and teenagers that were in progress that afternoon, sowing fear and forcing the removal of puppets, signs and banners. Then, on August 1, a 120-year-old Victorian trolley and bus barn serving as a puppet warehouse was surrounded by Philadelphia police. Activists in side refused to let police in without a warrant.

More than two

dozen police cruisers lined the avenue and scores of cops… surrounded

the warehouse. At least three helicopters hovered loudly above. A

handful of cops were on the roof and many had formed a barricade to

prevent people from approaching the building . . . . The city had staged

an elaborate drama full of hysteria and allegations to justify what it

was about to do.2

Police began using chainsaws to get into the building, but when a search warrant was obtained, the activists inside agreed to come out (but not with -out setting conditions, including that their lawyer be allowed to accompany police on their search of the building and that they have access to the media).

The search warrant was kept under seal for 30 days, allowing the city to conceal the fact that Pennsylvania State Police had ifiltrated the warehouse and that the “evidence” of illegal activity was based on the red-baiting of a right-wing think tank.

The

raid accomplished its goals: garbage trucks carted away “puppets,

signs, banners, leaÀets, and other political props,” along with personal

property including backpacks, clothing, identification, and the

equipment used to make the props like tools, paint, a sewing machine.

Deprived

of the visuals designed to convey their political message, protesters

had dif¿culty rebutting the City’s charge that they had no political

message and were just in town to make trouble.Seventy five people who

were present at the warehouse that day were arrested, jailed, and

zealously prosecuted, each charged with several misdemeanors and hefty

bails of $10,000 to $15,000.

Hermes takes us inside the jail with the over 400 people arrested on August 1 as they implemented a jail solidarity action. Activists spent their long hours of confinement, beginning while in the police buses, in spokes councils, discussing what jail solidarity would look like, making plans to engage in non-cooperation including refusing to identify themselves or be fingerprinted, refusing to move under their own power, locking arms and even stripping naked. Jailers responded with tactics of their own: using excessive force, denying needed medical attention and prescription drugs and other necessities, and sexual abuse and harassment.

Those tactics were met with further non-cooperation. On the outside, rallies, vigils and press conferences were organized, and R2K reached out to the faith community to secure its support. By August 6, about 150 arrestees began a hunger strike, but the city was unmoved, refusing to negotiate, demanding excessively high bails, denying access to lawyers, and delaying arraignments.

Many of those arrested on misdemeanor charges were detained for two weeks, some spent time in solitary confinement. They paid excessive bails and charges were not reduced. But, Hermes argues, the campaign “gained the support and solidarity of countless people in Philadelphia, across the country, and around the world.”3

He also notes that the goal of this solidarity action (unlike at the DC IMF/World Bank protests) was to include those people charged with felonies. Hermes and other activists assert that the refusal of those charged with misdemeanors to sever ties with those charged with felonies led to reduced felony bails.

Once the last arrestee was out of jail, the long-haul work began. Hermes detailed the excellent work of the R2K legal collective in keeping arrestees and their supporters informed, organizing meetings in several cities, promoting solidarity and a political trial strategy, and winning. In the end, 300 people were charged with misdemeanors, 43 with felonies. Out of those, 106 took plea bargains and 237 went to trial. Thirteen people were convicted of misdemeanors, one person took a felony plea bargain, but there was not one felony trial conviction, and none of those convicted were sentenced to jail.

This was an amazing outcome, particularly considering the city’s aggressive prosecution of the protesters. R2K Legal’s true forte was public relations. Hermes notes a “discernable shift in public opinion” as the collective publicized the string of dismissals and acquittals, and the extensive ifiltration that the legal process exposed.

Coverage of the trials and the sham of the preemptive arrests was not limited to Philadelphia. The regional and national press picked up the story. R2K ensured that the mass arrests, designed to quiet protests and enhance the city’s image, back¿red.

By all accounts, the court solidarity and political trial strategy had been wildly successful. Combining resistance, theatrics, and repeated legal victories with an effective PR campaign did more than vindicate the hundreds of defendants. It also served to embarrass the city for its role in silencing dissent.

Most important to the R2K Legal Collective and all of the RNC defendants, however, was safeguarding those accused of felonies.4

As

the criminal cases wended their way through the courts, R2K Legal began

to develop a civil litigation strategy, drafting a proposal laying out

the “structural relationship between activists, attorneys, and the R2K

Legal Collective” that would give more power to activists. By January

2001, R2K Legal had launched a months-long process involving meetings

with activists in various cities to discuss strategies and hammer out an

agreement on how civil suit costs, labor, and monetary awards would be

divided. Activists were adamant that their political demands for

injunctive relief would be included in the lawsuit, and that any money

won would be pai

d out to activist groups rather than to individual

activists. On August 1, 2001, a year after the raid on the puppet

warehouse, a civil suit was ¿led demanding damages and injunctive relief

including “better safeguards against surveillance and infiltration, and

stricter enforcement of habeas rights and timely arraignments.”5

A month later, R2K Legal and the rest of Philadelphia learned about an insurance policy the city had bought prior to the convention to protect police from liability for “things like false arrest, wrongful detention or imprisonment, malicious prosecution, assault and battery, discrimination, humiliation, violation of civil rights.”6

That insurance policy allowed the city to hire a high-powered law ¿rm to defend them in civil suits, turning the “slam dunk” puppet warehouse lawsuit into a vehicle for the city to harass activists and activist groups with numerous and wide-ranging subpoenas and depositions.

The city’s strategy drained the time and resources of R2K Legal, the activists and their lawyers, whose priority still remained the ongoing felony trials. The city’s strategy also brought the other half-dozen or so civil suits to heel. A gag order on all the settlements means that we don’t know the dates on which they were settled or the terms, but over the spring and summer of 2001 they all appear to have been settled. Luckily a transcript from a closed hearing in the puppet warehouse case was inadvertently filed as a public document.

The Philadelphia Daily News reported that an award of $72,000 would be paid out of the city’s insurance policy.7

While

the civil litigation strategy didn’t get the results desired or

expected, the work R2K Legal did to create a framework to empower

activists and elevate their political priorities was groundbreaking.

What

to make, then, of the Philadelphia experience? Arguably, it is in the

realm between the legal world and the world of political organizing

where, when boundaries are pushed, unexpected results can occur. The

successes of R2K Legal came from a combination of legal and political

strategies developed by activists and defendants.8

There was a brief renaissance of legal collectives in the early 2000s, but too many were short-lived, organized around a single event, or, for whatever reason, just unable to survive. These groups were democratic. They sought to empower activists and ensure that political goals would not be undermined by police and legal processes. The demise of so many of them has created a vacuum—just as the powers of the state have ascended in the post-9/11 era.

How will legal workers collaborate with political comrades and attorneys to develop creative means of keeping dissent alive and thriving in the new era of increased state surveillance and disruption?

It’s a crucial question for the National Lawyers Guild—one Hermes, by sharing instructive stories from a past struggle, helps to answer.