by Kurt Wilcken

Daily Kos

July 21st, 2013

Back in the 1980s, writer John Shirley was on the cutting edge of the Cyberpunk movement in science fiction. Athough Cyberpunk has faded and its tropes and memes cut up and assimilated into the SF Mainstream, Shirley continues to write raw and imaginative fiction.

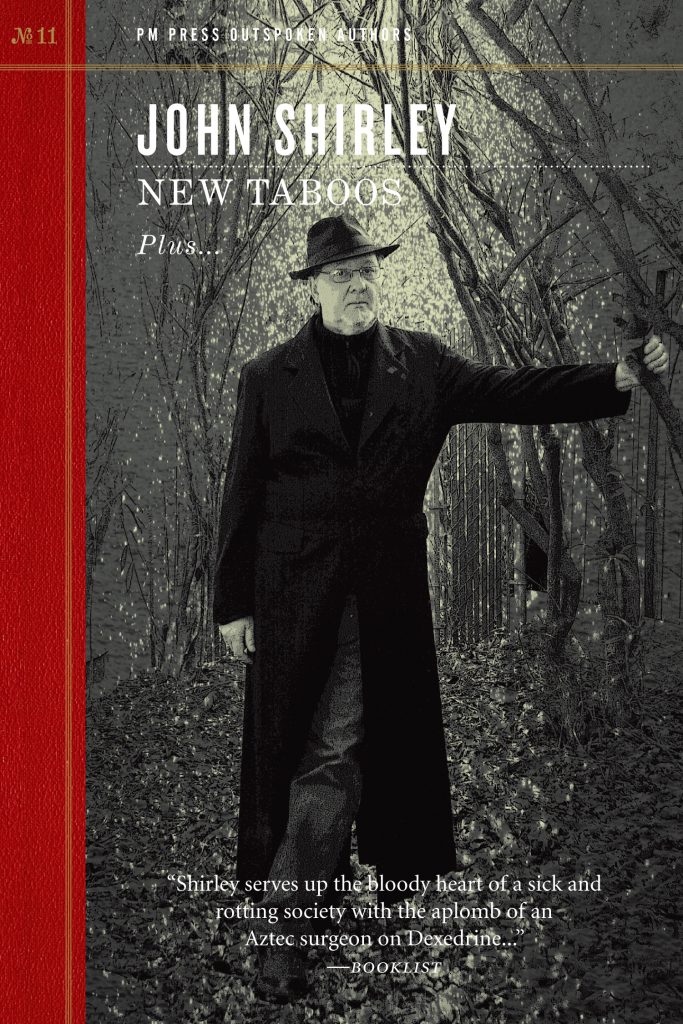

Several months ago, I reviewed his most recent novel, Everything Is Broken, a cautionary tale about why having a government small enough to drown in a bathtub is of little help when the water gets really deep. I recently received another book by Shirley titled New Taboos.

New Taboos is part of the “Outspoken Authors” series published by PM Press, presenting material from some notable literary voices. The book is a collection containing a novella, a couple essays and an interview with John Shirley.

“A State of Imprisonment” is a novella which extrapolates the current trend toward privately-run, for-profit prisons to its logical conclusion. It’s set in the near future, where nearly the entire state of Arizona has been converted into a maximum security prison run by a large company. (To be fair, only 80% of the state has been converted into the prison; the Grand Canyon, presumably, has been set aside for the tourists).

The prison is run on the cheap, to maximize profits, and the company gets paid by the prisoner, so they subcontract out to house delinquent debtors as well as political prisoners from other countries. They also use every means possible to extend each prisoner’s sentence. As a private entity, the business has very little government oversight. What happens behind the walls stays behind the walls. And if any prisoner tries to escape, he has to face the Worm: crawling robot drones that locate and terminate fleeing prisoners.

Faye Adullah is a reporter for a major internet news service who wrangles permission to do a story on Arizona Statewide Prison. Statewide does not particularly like transparency and obstructs her in every way possible, but Faye is determined to get her story.

In the middle of the carefully-choreographed tour, something unexpectedly goes wrong. The power goes out, and Faye finds one of the prisoners at her side urging her to come with him. He has arranged the blackout — the prison was built on the cheap, so it is not that difficult to overload the electrical system if you know how — so that he can get Faye away from her minders and show her what really goes down at the prison.

Faye gets a bigger story than she imagined, but it’s a story that Statewide will never let her publish. She quickly finds herself a prisoner on fabricated charges, with her only avenues for justice in the hands of a corporation with a strong profit motive to keep her locked up forever.

Accompanying the novella are two essays. “New Taboos”, from which the collection takes its title, discusses the idea of the taboo, not as an arbitrary prohibition, but as an expression of societal values. We saw something like this just recently with Paula Deen’s adventures in ill-advised remarks, but Shirley takes it further.

What if the phrase “Obscene Profits” were not just a figure of speech? What if the practice of amassing huge profits while exploiting one’s employees, or while contaminating the environment, or while lying to the public, was actually regarded as revolting, and the people who engaged in such practices were shunned as pariahs?

On the adult scale, we have laws againt some of these social transgressions, but much of the time they’re unenforceable. Taboos — if we really integrate them into our society — enforce themselves, for the majority of people. If the taboos are deeply ingrained enough, we don’t need the laws.

In Shirley’s view, these taboos would only be a stage; an artificial but necessary framework until we deveolped as a society and as a culture so that such rules would not longer be needed. I’m not sure how these taboos would be instituted, nor how well they would work if they were, but here he is more thinking aloud than formulating a plan. And his modest proposal suggests a different way of looking at some of our society’s faults.

“Why We Need Forty Years of Hell” is a TEDx address John Shirley delivered in 2011 offering a grimly optimistic view of the next few decades. Optimistic, because he believes things will get better… eventually; grim because he is convinced that the only way people will make things better is when — not if — things get so bad that we are forced to clean up our act.

He touches on several aspects of the future which are already on top of us now: climate change, ecological damage, crises in food production, the social ramifications of the widening gap between rich and poor, and the dark side of technology. It’s all interconnected, and that indeed is the lesson we need to learn.

We’ll have astounding technological advancements against a backdrop of grievous social inequity and quite possibly increasing barbarity, for a period, until we are forced by waves of crises to come to terms with the consequences of developing a civilization blindly. Wars, plagues, radical separation of privileges, famines due to climate change and other environmental consequences, will force humanity to accept Buckminster Fuller’s “Spaceship Earth” concept as very real.

In the end, he feels that humanity will eventually achieve the kind of rational, integrated approach to society, the environment and each other that we need; but only after harsh experience hammers in the understanding that “we can’t treat Spaceship Earth as a party cruise ship.”

Rounding out the volume is an interview with Shirley, touching on many facets of his varied career. He talks about cyberpunk and writing, doing lyrics for Blue Öyster Cult and the screenplay for The Crow, being attacked by wild monkeys, and about his politics. He describes how seeing pictures of the My Lai massacre as a boy radicalized him and how, although a lifetime of experience has tempered his views, he still has a socialist streak in him. He strongly dislikes the Tea Party Movement and the Neo-Randites, which comes out strongly in his novel Everything is Broken.

The interview is a bit disjointed and reads like the interviewer submitted a list of questions rather than engaged Shirley in a conversation. I’ve conducted interviews that way too, so I suppose I shouldn’t criticize; and the interview does allow Shirley to comment on a wide variety of subjects. Still, I would have liked to see the interviewer follow up on some of the questions and allow Shirley to expand upon his answers.

New Taboos is a slim volume offering an intriguing sampling of John Shirley’s writing and ideas. It’s worth a read.

Now I need to tackle his A Song Called Youth Trilogy.