By Diane Lefer

LA Progressive

December 4th, 2015

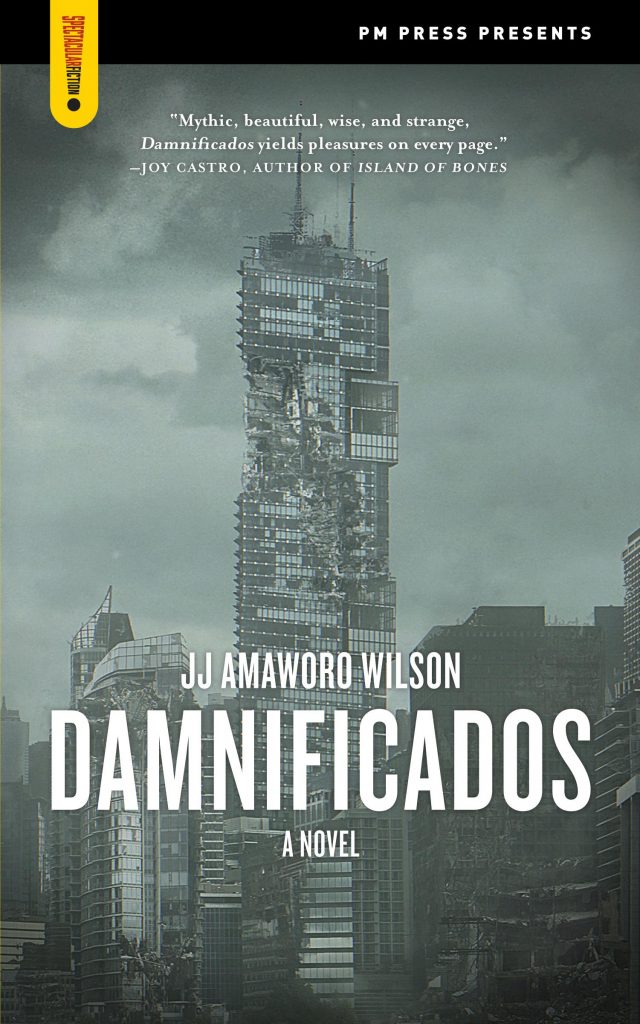

I‘ve never met JJ Amaworo Wilson (though I hope to remedy that soon) but when he contacted me, hoping I would read and comment on his work, I said yes. His publisher is known for radical and stimulating fiction, the author’s website intrigued me and so did the premise of his novel, Damnificados.

So here’s the advance word on some extraordinary fiction. Welcome to a world of two-headed wolves where people go to war over trash and thousands of the desperate move into an unfinished skyscraper tower built on a base of compacted garbage. The squatters learn “how to build a community from this upright tomb” in defiance of the most violent, ruthless, politically connected family imaginable. The Torres family, with control of the Army, the police, and the government, continues to lay claim to the Tower.

Welcome to a world of two-headed wolves where people go to war over trash and thousands of the desperate move into an unfinished skyscraper tower built on a base of compacted garbage.

Wilson, born in Germany to an English father and Nigerian mother, has worked and traveled throughout the world, extensively in Latin America, and his novel’s setting has a Latin American feel. Which is appropriate: though it takes place in an imaginary and globalized space, Wilson was inspired by the real-life occupation of the Tower of David in the financial district of Caracas, Venezuela. In 2007, more than two thousand of the city’s damnificados, or homeless, moved into the shell of a luxury building after financing fell through and construction stopped. The squatters were led by a controversial figure–a reformed criminal who may or may not have been truly reformed. The site inspired scenes in the TV show Homeland where it was, of course, portrayed as a frighteningly violent place. Wilson sees it differently.

Though the term damnificado has its particular meaning in Caracas, I am struck by the word’s resonance. Obviously, English-speakers see damned while the Spanish word can be translated as victim or survivor or the meaning I like best: damaged–in the sense of being an injured party, someone entitled to seek recompense or redress. Today’s global poor are indeed the survivors of the violence of global economic crime. Where, how can they seek redress?

Wilson’s damnificados emerge from “cardboard cities” and hillside shanty towns where “ramshackle houses crowd together, climb upon one another as if for comfort.” Some of the damnificados have “wrapped their faces in cloths, like lepers, only eyes visible, and their steps are padded as a panther’s because many have no heels to walk in, just rags binding their feet or shoes with worn rubber soles. And others move barefoot, hunched and furtive, two by two, shifting in the shadows for safety.”

They are led—though he would prefer the community remain leadership—by Nacho Morales, who heaves his wasted body through the days on bandaged crutches. Born only to be abandoned on a river bank, swaddled in rags, he has the good fortune to be found by a storytelling schoolteacher. Unable to run or fight, he’s also lucky to have a big brother Emil with a knack for showing up in the nick of time. Nacho becomes a voracious reader and a linguist as “languages stick to him like mud to a boy’s knee.” And there are many languages in the world of the novel. Characters speak Spanish, Portuguese, German, Arabic, Italian, Creole, Latvian, Tagalog, French, Gujarati and more. The Tower is a veritable Tower of Babel. The squatters may not always use politically correct speech: the giant hero is referred to always as simply The Chinaman. But unlike what happens in the Scriptural Tower of Babel, the squatters aren’t confused and confounded by difference. They cooperate.

Brazilian novelist Jorge Amado surely put many nationalities in the streets of Bahia, but he was celebrating the mixing of races and cultures while Wilson’s take on diversity seems to me to reflect the globalization of poverty and oppression. And like Amado, when Wilson’s narrative enters mythic territory, this isn’t so much magic realism–reporting supernatural occurrences as if factually true–as the recognition that gossip, exaggeration, and legend are part of history, too.

Turning contemporary realities to legend takes a talent as rare and special as JJ Amaworo Wilson’s. Through his narrative rich in danger, adventure, humor, romance, and risk, he can raise essential questions without succumbing to earnestness or didacticism. How can the damnificados of the earth assert their dignity and take control of their own destinies? Where do you turn when all the forces of so-called law and order are the oppressors and assassins. How can anyone live nonviolently in a violent world which is always ready to dispossess human beings of their homes, those they love, and their lives? Damnificados takes us to the limits of the possible.

When Nacho starts teaching the adults and then the children in the Tower, the priest who’s taken up residence warns him literacy leads to revolution. When people read about their rights, they learn they’ve been exploited throughout history. Then: “If the government comes for us, we’ll all be dead.”

Nacho replies “someone always survives. There’s always some poor wretch who gets out alive and spreads the word.”

Which reminds me of a story I heard decades ago from the great Nigerian writer Chinua Achebe. I expect the author of Damnificados knows it too and I hope he’ll forgive me if my memory causes me to retell it wrong. A lion has a rabbit in its jaws, and the rabbit begs for just a minute more of life to say its prayers. The lion releases it and the rabbit, instead of praying, lies on its back in the dirt and thrashes about raising dust. “What good did that do you?” the lion asks. And the rabbit says, “Anyone passing by this road will know a great struggle happened here.”

Thank you, JJ Amaworo Wilson for your eloquent fiction that entertains even as it advances the very necessary struggle of our much-afflicted world.