By Ron Jacobs

Dissident Voice

October 9th, 2010

In recent weeks, articles have appeared in various media outlets detailing recent surveillance activities of the FBI and other law enforcement agencies. According to these reports. much of this surveillance was focused on antiwar and peace groups. Then, on September 24, 2010 several homes and offices in Minneapolis/St. Paul, Chicago and North Carolina were raided by the FBI. Subpoenas to appear at a grand jury investigation were issued to several activists. The reason provided for the raids was that some individuals were suspected of providing “material support to terrorists.” These raids and recent revelations have been met with protest and, in some quarters, shock-as if the United States government were somehow above such police state intimidation and practices.

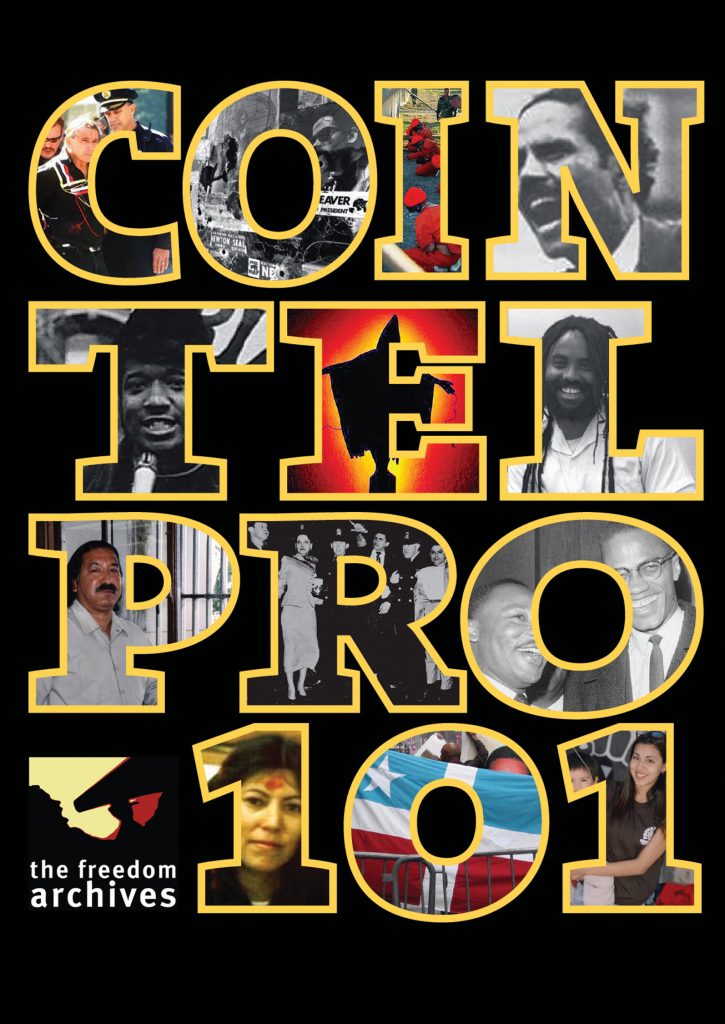

On October 10, 2010 at the Mission Cultural Center of Latino Studies in San Francisco, the Freedom Archives will premier its latest documentary. Titled Cointelpro 101, this hour-long film makes it quite clear that the US government is certainly not above such practices and that, furthermore, it has a long history of them. For those who don’t know, Cointelpro was the abbreviated name for the intelligence and counterinsurgency operation waged against a multitude of organizations and individuals deemed threats to national security during the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s by the FBI and other US law enforcement and intelligence agencies. Short for counterintelligence, Cointelpro involved the use of a multitude of methods up to and including murder in its crusade to neutralize any and all left opposition to the status quo in the United States. From Martin Luther King, Jr. to the Weather Underground Organization, any one considered an enemy of the US national security state because of their opposition to the US war in Vietnam or their support for the self-determination of people of color in the United States was a potential target of the Cointelpro program.

Cointelpro 101 opens with the April 1971 break-in by antiwar activists at the federal offices in Media, Pennsylvania. The activists were searching for Selective service files to destroy when they came upon files labeled Cointelpro. After a quick perusal of the file’s contents, they removed as many as they could find from the office, made copies and released them to the press. The program was unknown to the broader public at the time and the files proved a revelation to the country. Many politicians were offended and, after the 1972 discovery of the Plumbers unit run by G. Gordon Liddy under the direction of the Nixon White House and the subsequent months of Congressional hearings around Watergate, Senator Frank Church called for hearings to investigate the Cointelpro program.

As the history related in the film makes clear, Cointelpro’s stretch was broad. Beginning in the 1950s with a focus on the Puerto Rican independence movement and continuing through the 1960s and into the 1970s when much of its focus had shifted to the black liberation, Chicano liberation and American Indian movement, the program racked up a number of assassinations, false imprisonments and ruined lives. No government official was ever punished for actions taken under the program’s auspices. The film details this history through the artful use of still photos and moving images of the period covered. Films of police attacks and protests; still photos of revolutionary leaders and police murders graphically remind the viewer of Washington’s willingness to do whatever it takes to maintain its control. Organizers who began their political activity during the time of Cointelpro discuss the effect the program had on them and the organizations and individuals they worked with. Indeed, several of the interviewees were themselves targets and spent years in prison (some on charges that were false, as in the case of Geronimo ji-Jaga Pratt) or on the run. One of the interviewees, Wesley Swearingen, is a former FBI agent who was involved in Cointelpro operations in Los Angeles and elsewhere and later published a book exposing his knowledge. His recollections reveal the nature of the war the FBI was fighting.

Former Black Panther member Kathleen Cleaver states toward the end of the film that Cointelpro represented the efforts of a political police force making the decision as to what is allowed politically and what is not. Anything outside the parameters set by this force was fair game. Nothing that was done by government officials or private groups and individuals acting on the government’s behalf was perceived as wrong or illegal. As Attorney Bob Boyle makes clear in his final statement in the film, Cointelpro is alive and well. The only difference now is that most of what was illegal for the government to do during Cointelpro’s official existence is now legal. The PATRIOT Act and other laws associated with the creation of the Department of Homeland Security have insured this. The September 24, 2010 raids mentioned above are but the most recent proof of it.

Cointelpro 101 is a well made and appealing primer on the history of the US police state. Produced, written and directed by individuals who have themselves been the target of tactics documented in the film, it has an authenticity and immediacy that pulls the viewer in. Although too short to cover the history in as full detail as some may desire, the film’s intelligence and conscientious presentation of the historical narrative makes it a film that the student, the citizen and the activist can all appreciate.