By Henrietta Cullinan

Peace News

October 2015- November 2015

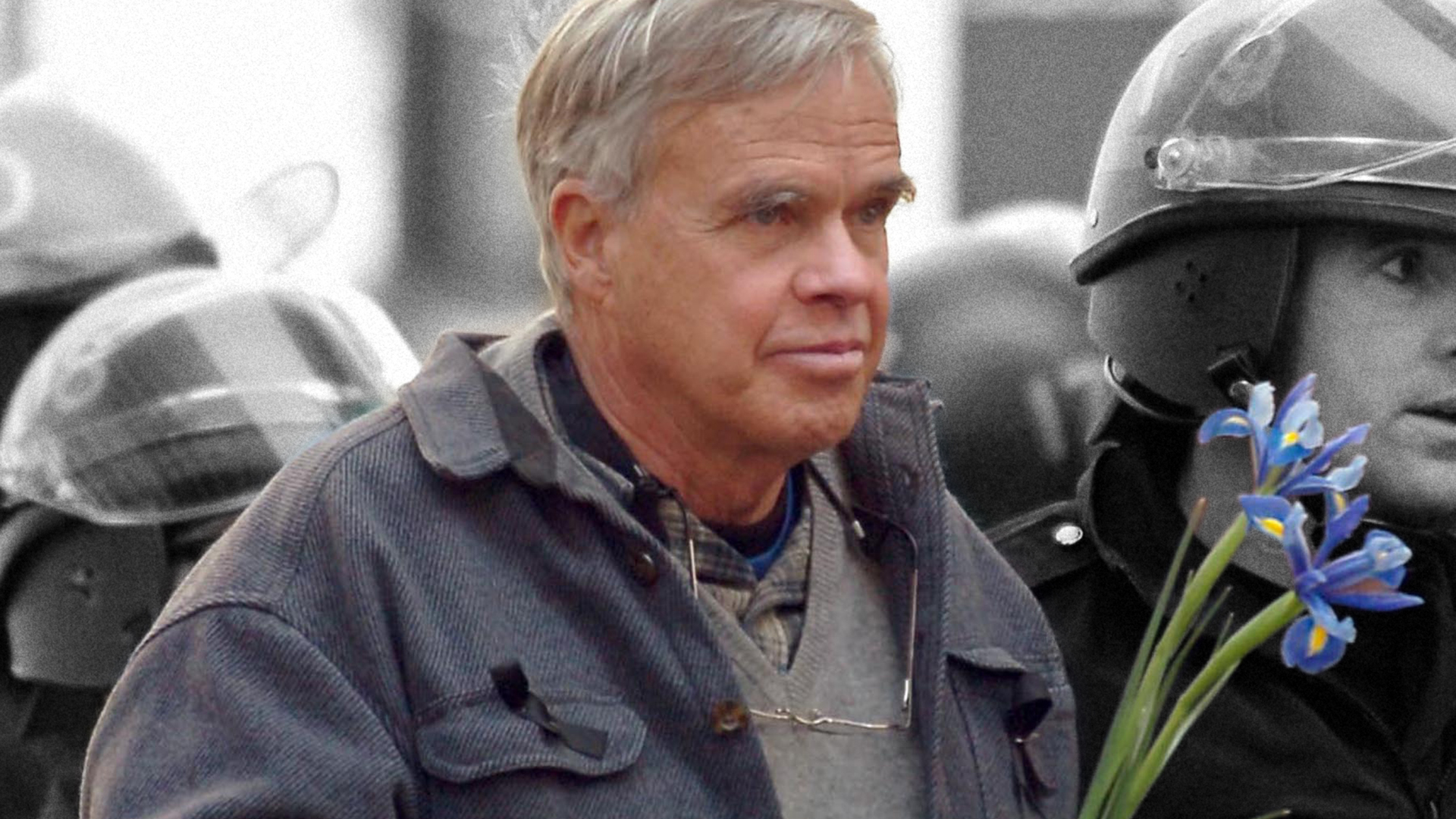

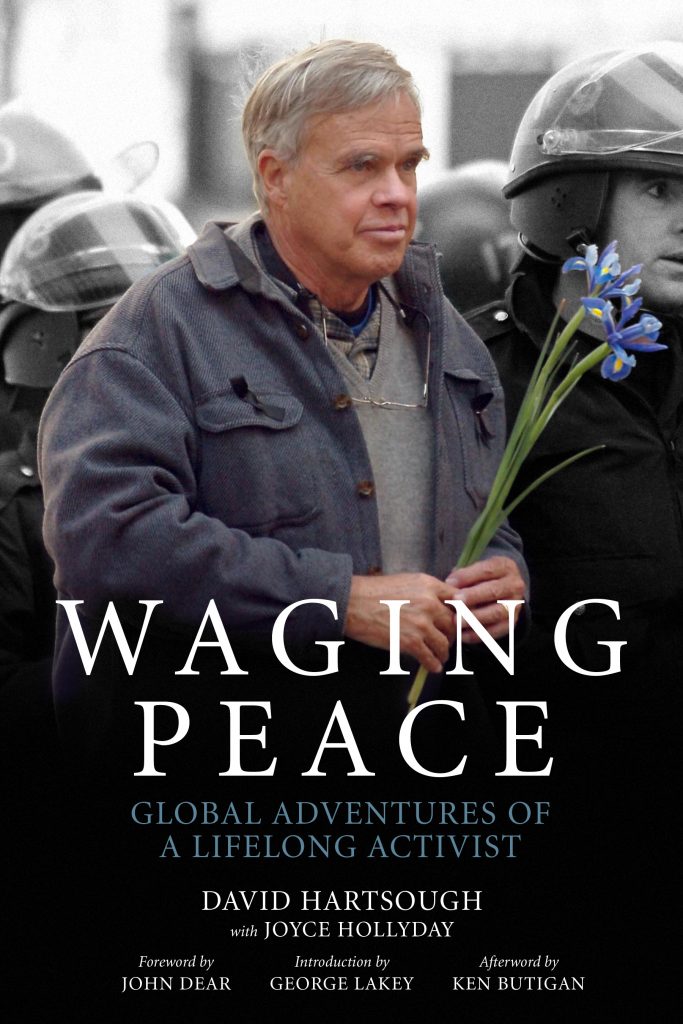

The front cover of this book – a portrait of the author holding an iris in both hands whilst hemmed in by riot police – shows a kind, thoughtful-looking man, who one can well imagine meeting on a peaceful protest here in Britain. However, this image belies the book’s central message: if I believe that my life is no more important than anyone else’s, then I need to be prepared to put my own life in danger.

Several examples are provided by the ‘spiritual giants’ the author has met during his life as a committed peace worker. Thus Hartsough recalls a summer of organising with Brian Willson, a Vietnam veteran who, during protests in California, lay on the railway line in front of a train carrying munitions bound for Central America. Horrifically, the train did not stop and rolled over his body, inflicting life-threatening injuries. Willson had stated: ‘We are not worth more. They are not worth less’.

In another example, this time from Mexico, Hartsough accompanies a priest back to his village which has been occupied by the military. Padre Joel says: ‘My life is life only if I am willing to hand it over.’

Hartsough voices the hope that he too can show this courage, later quoting an even harsher judgement by Daniel Berrigan: ‘We have assumed the name of peacemakers, but we have been, by and large, unwilling to pay any significant price.’

During the course of the book, we learn about the author’s own part in daring protests, such as the 1972 ‘People’s Blockade’ that attempted to obstruct the passage of the Vietnam-bound USS Nitro with a fleet of canoes. There are also powerful first-hand accounts of nonviolent direct action taken by groups under threat in places including Central America and the Philippines. And Hartsough also records being present at a number of remarkable historical events. For example, in Russia, when the people encircled the ‘White House’ to protect their democratically-elected government from a military coup.

I greatly appreciated reading the author’s accounts of the peace delegations he has led to conflict zones all over the world. The delegates were not always welcomed, and sometimes their lives, and the lives of the groups they visited, were threatened. But I also found encouraging the importance he gives to the smaller kinds of actions that one might think make hardly any difference.

For example, Hartsough stresses the importance of enabling the old and frail to protest, and recalls accompanying his own parents, even to the point of being arrested with them. These well-told stories will help motivate contemporary peace activists – especially since even now, at 74, Hartsough himself keeps up the pace, protesting at drone bases.

Incorporating some of the author’s own sentencing statements, some practical methods for action planning, and his ‘Ten Lessons’ of peacemaking, this book is a valuable resource as well as a radical and powerful testament to the effectiveness of committed nonviolent peace work.