By Ken Butigan

Waging NonViolence

November 12th, 2014

Years ago, my friend Anne Symens-Bucher would regularly punctuate our organizing meetings with a wistful cry, “I just want to live an ordinary life!” Anne ate, drank and slept activism over the decade she headed up the Nevada Desert Experience, a long-term campaign to end nuclear testing at the Nevada Test Site. After a grueling conference call, a mountainous fundraising mailing, or days spent at the edge of the sprawling test site in 100-degree weather, she and I would take a deep breath and wonder aloud how we could live the ordinary, nonviolent life without running ourselves into the ground.

What we didn’t mean was: “How do we hold on to our radical ideals but also retreat into a middle-class cocoon?” No, it was something like: “How can we stay the course but not give up doing all the ordinary things that everyone else usually does in this one-and-only life?” Somewhere in this question was the desire to not let who we are — in our plain old, down-to-earth ordinariness — get swallowed up by the blurring glare of the 24/7 activist fast lane.

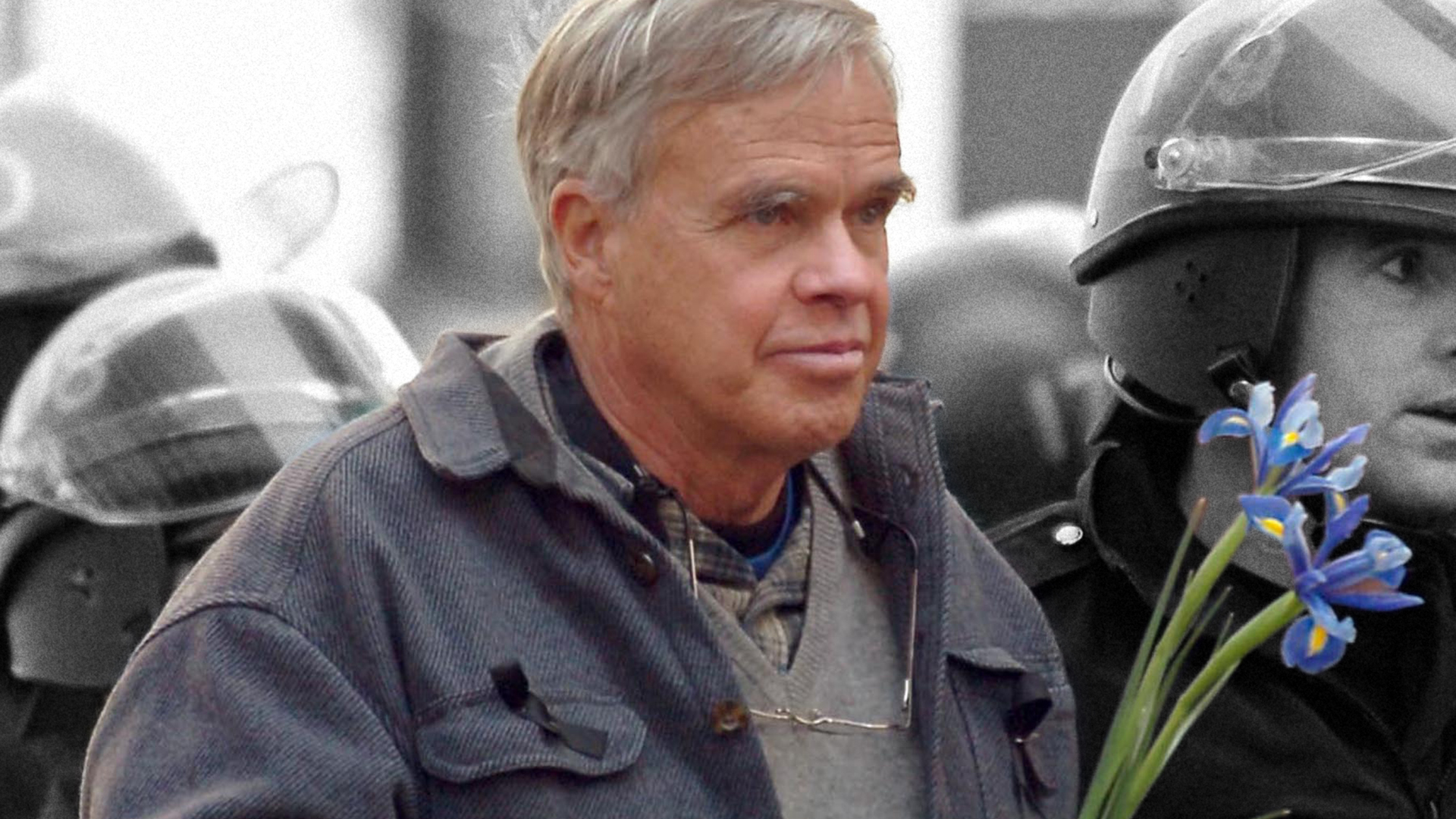

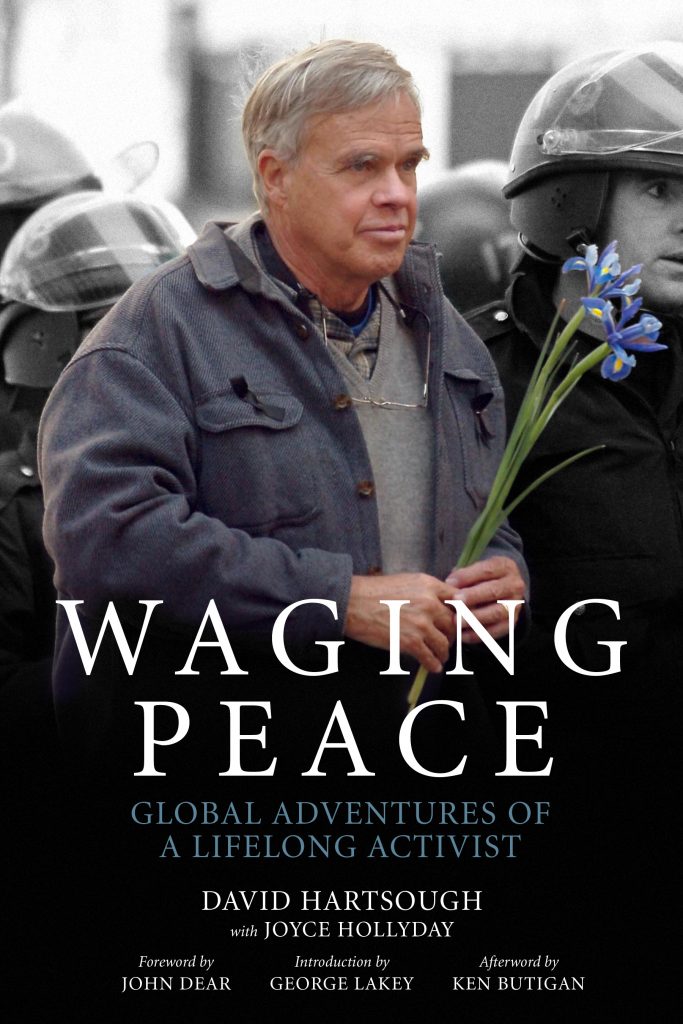

These ruminations came back to me as I plunged into the pages of David Hartsough’s new memoir, “Waging Peace: Global Adventures of a Lifelong Activist.” David has been a friend for 30 years, and over that time I’ve rarely seen him pass up a chance to jump into the latest fray with both feet — something he’d been doing long before we met, as his book attests. For nearly six decades he’s been organizing for nonviolent change — with virtually every campaign, eventually getting tangled up with one risky nonviolent action after another. Therefore one might be tempted to surmise that David is yet another frantic activist on the perennial edge of burnout. Just reading his book, with its relentless kaleidoscope of civil resistance on many continents, can be dizzying — what must it have been like to live it? If anyone would qualify for not living the ordinary life, it would seem to be David Hartsough.

As I finished his 250-page account, however, I drew a much different conclusion. I found myself thinking that maybe David has figured it out — maybe he’s been living the ordinary life all along.

Which is not to downplay the Technicolor drama of his journey. Since meeting Martin Luther King, Jr. as a teenager in the mid-1950s, David has been actively part of many key nonviolent movements over the last half-century: the civil rights movement, the anti-nuclear testing movement, the movement to end the Vietnam War, the U.S. Central America peace movement, the anti-apartheid movement, and the movements to end the U.S. wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. In recent years he has helped found the Nonviolent Peaceforce and a new global venture to end armed conflict, World Beyond War.

This book is jammed with powerful stories from these efforts — from facing down with nonviolent love a knife-wielding racist during an eventually successful campaign to desegregate a lunch-counter in Arlington, Va., in 1960, to paddling canoes into the way of a U.S. military ship bound for Vietnam; from meeting with President John Kennedy to urging him to spark a “peace race” with the Soviet Union, to being threatened with arrest in Red Square in Moscow for calling for nuclear disarmament there; from confronting the death squad culture in Central America and the Philippines to watching his good friend, Vietnam veteran Brian Willson, get mowed down by a U.S. Navy munitions train.

These are just a few of innumerable vignettes of David’s peacemaking around the world. But there is much more to David’s life story than these intense scenes of nonviolent conflict.

Much of this book recounts how the foundations of his career as an agent of nonviolent change were laid, slowly and organically. His decision to give his life to peacemaking was shaped by the inspiration of his parents, who were both actively involved in building a better world, and by a series of experiences in which he witnessed the impact of violence and injustice, but also at the same time met a series of remarkable organizers who were not content to simply wring their hands at such destruction, including the likes of civil rights movement luminaries Bayard Rustin and Ralph Abernathy.

Most powerful of all, David set out on a series of illuminating explorations, with long stints in the Soviet Union, Cuba and a then-divided Germany. Everywhere he met people who turned out to be complicated, beautiful and often peace-loving human beings. His nonviolence — and resistance to war — was strengthened by seeing for himself the people his own government deemed “the enemy.”

In Berlin — a city split between the East and West after World War II, but not yet separated by the wall the Soviets would build — he took classes on both sides of the divide and experienced up close what the “us” versus “them” of violence feels like: “In the mornings [at the university in the East] I would challenge the Communist propaganda and be labeled a ‘capitalist war-monger,’” he writes. “In the afternoons, at the university in the West, when I challenged their propaganda I was called a ‘Communist conspirator.’ I thought I must be doing something right if neither side appreciated my questions! I didn’t consider myself any of these things: capitalist, war-monger, Communist, conspirator.” Instead, he was a nonviolent activist challenging the confining labels that are used to foment the separations that fuel and legitimate violence and injustice.

David has rooted his lifelong pilgrimage of peace in a simple conviction: that all life is precious. He has helped spark and build one campaign after another when that preciousness is forgotten or undermined.

At the same time, he’s recognized that such a nonviolent life extends to himself. This is where the ordinary life comes in.

David and his spouse Jan live a simple life interweaving family time (including with their children and grandchildren, who live downstairs from them) with building a better world. They are activists, but they rarely let organizing keep them from taking a hike in the mountains or a walk along the seashore. They are regulars at the local Quaker meeting. For decades they have been sharing their home with countless friends, who are often invited to the songfests that they frequently organize in their living room. When I stay with them in San Francisco, there is always a bike ride through Golden Gate Park to be had or time to be spent at a garden a few blocks away with its dazzling profusion of azaleas. Rather than giving short shrift to the fullness of life, David has found a way to live, as we say today, holistically.

David’s life qualifies as “ordinary,” though, not only because it knits together many dimensions of everyday realities, but because it has dissolved the artificial boundary between “activism” and “non-activism.” All of life is an opportunity to celebrate and defend its preciousness, and this impulse gets worked out seamlessly in both watering the plants and getting carted off to a police van after engaging in nonviolent resistance at a nuclear weapons laboratory. Nonviolent action is a seamless part of the rhythm of life. It is a crucial part of the ordinary life. Once enough of us see this and fold it into the rest of our life, its ordinariness will become even more evident than it is now. This was Gandhi’s feeling — nonviolence and nonviolent resistance is a normal part of being human — and David has taken this assumption up in a clear and thoughtful way.

Anne Symens-Bucher reports that she’s increasingly living the ordinary life — she’s developed a powerful example of it called Canticle Farm in Oakland, Calif. And I feel I’m getting closer to it day by day. But if you want to read a page-turner that reveals how one person has been doing it for the last 50 years, get a copy of David Hartsough’s new autobiography, Waging Peace.