by Martha Hennessy

National Catholic Reporter

March 16th, 2016

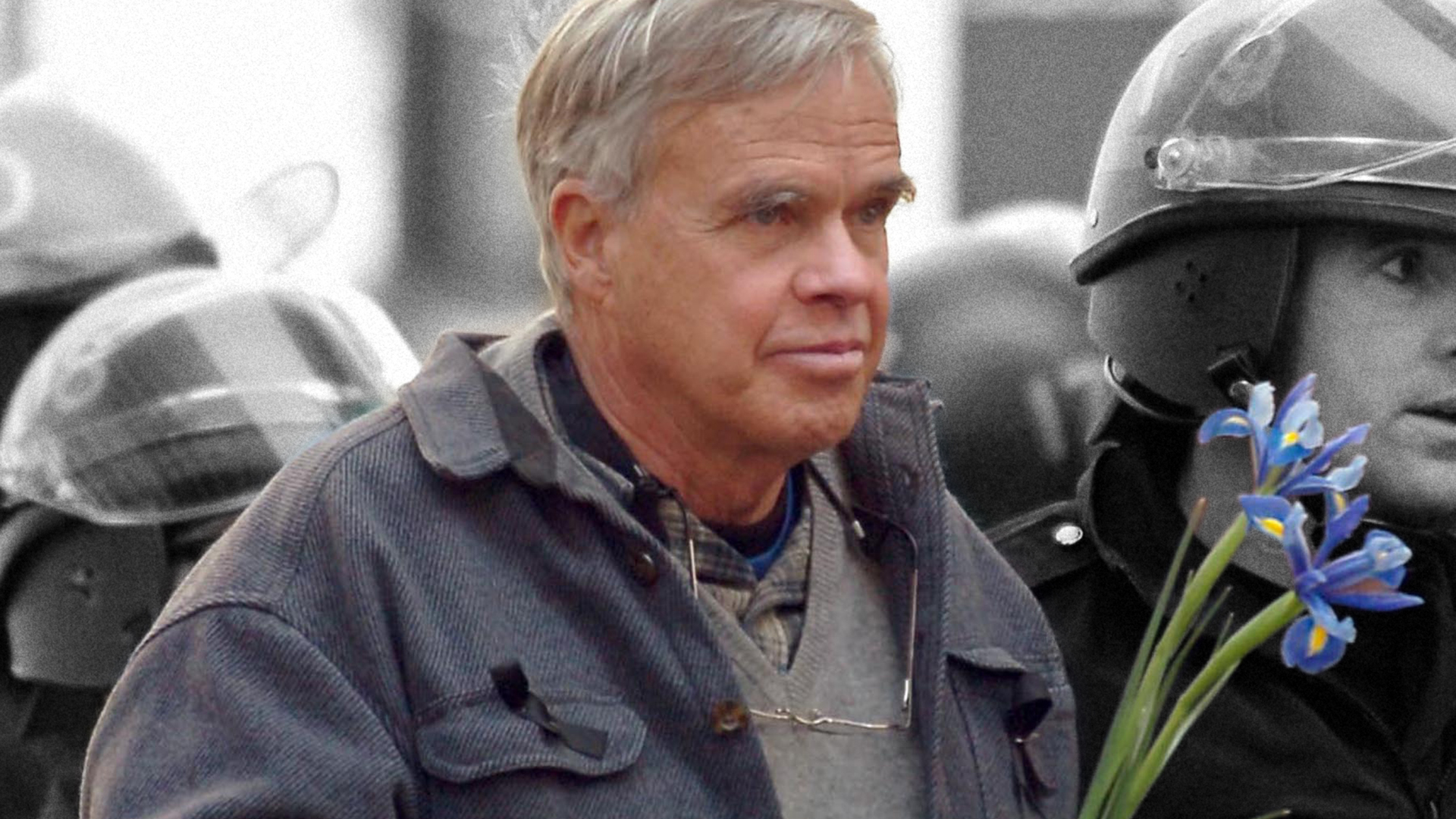

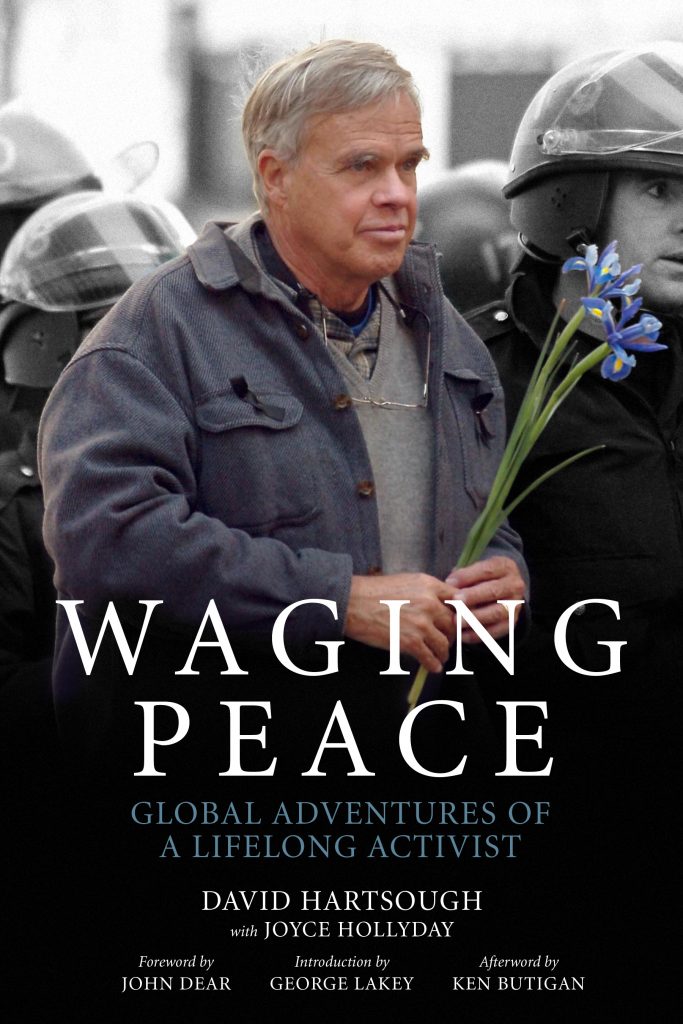

David Hartsough has given us a remarkable story of his life as a persistent and insightful peacemaker of our times. His wanderlust and astute eye for critical events around the world brought him to many of the right places at the right times.

A fine example was set for Hartsough in his childhood through the work of his father, a Congregational minister. Ray Hartsough answered the call of the Quaker service organization and was sent to Gaza in 1948 to lend assistance to refugees as a result of the Arab-Israeli War. As a child, David gained an immediate sense of the suffering of others and what is required to put one’s faith into action to help bring peace and justice into the world.

As a young man in 1960, Hartsough spent a year in divided Berlin, where he studied postwar effects just 15 years after the end of World War II. Three critical observations came to him in these formative years. The ravages and suffering of war were still evident in the souls and neighborhoods of the German people. The U.S. and Soviet rivalry for influence and control dictated how the people lived, forcing them from hot war to cold war.

A second revelation came to Hartsough as he witnessed the depth of faith practiced by both Catholics and Protestants while visiting churches. This prompted him to take a serious look at what it means to be a Christian, asking how we are to practice the teachings of Matthew 25 within the reality of a world of mass suffering, starvation and the ever-present threat of nuclear self-annihilation.

Hartsough’s third query strove to understand the human desire not only for adequate work, housing, food and health care, but also our yearning for freedom and self-actualization. Neither the West nor the East allowed a place for people to honestly speak out against cultural materialism, a restrictive bureaucracy and the constant demonization of each other. Where is true democracy to be found when society, churches, universities and media fail to question this siege mentality?

The long history of insatiable empire-building on the part of the United States is well-documented in this revealing book. In a meeting at the Soviet Peace Council in Moscow, Hartsough was told by the director and editor of the Young Communist newspaper that efforts were made on the part of Russia to de-escalate the mounting tensions at the time of the building of the Berlin Wall. It was felt that the U.S. continued the arms race despite the efforts made by the USSR for disarmament with a unilateral halting of nuclear testing in 1958, abolishing all military bases outside of its borders, and cutting 2 million troops from its forces.

Within a year of this meeting and five months before the Cuban Missile Crisis, in May 1962, Hartsough and a delegation of Quakers met with President John F. Kennedy at the White House. Hartsough was the youngest person present, and the group asked the president to unilaterally stop the testing of nuclear bombs and to challenge the Soviets to a “peace race.”

The president’s attention was caught by these peacemaking Quakers. In a speech at American University, he did propose a ban on nuclear testing and the idea of a peace race. Kennedy was killed five months after that speech.

Hartsough’s history of peacemaking includes his witness to the U.S.-backed wars in Central America in the 1980s. Again, the suffering of innocent people struggling to sustain themselves on the land while enduring assaults from corporate-driven interests is an appalling history. The effect of such unspeakable violence continues to haunt these small countries to this day.

In reading this book, we are forced to look at ourselves and to acknowledge that our chosen lifestyles rely on war-making to attain such a high standard of living. The practice of American exceptionalism attempts to justify our consumption of massive amounts of the world’s resources at the expense of the majority of the population.

Hartsough unfailingly identifies the places where nonviolent witness remains desperately needed. But beyond that, he also suggests the means by which we can confront the evil of greed-induced violence and sustain a long-term effort in bringing the transformative power of peacemaking efforts into the 21st century.

This means going to the margins and accompanying the people who suffer the results of U.S. foreign policy. It means living a simple life so that resources are more equitably shared.

Perhaps most importantly, Hartsough reminds us of the crucial role that community, family and friends play in carrying on the work of peacemaking.

[Martha Hennessy divides her time between family in Vermont and work at Mary House Catholic Worker. Her peacemaking efforts include travels to war-torn and occupied countries.]