by Sara Falconer

The Monthly Review

Volume 64, Issue 10

March 2013

I started writing to David Gilbert and several other North American political prisoners in 2001, shortly after 9/11. To say that these correspondences, beginning at such a turning point in history, played a huge role in my political development feels like something of an understatement.

Everything in me has grown stronger through my work with prisoners. My analysis of movements, past and present. My understanding of the brutal lengths the state will go to crush dissent. My awareness of the prolonged nature of this struggle. My commitment to it.

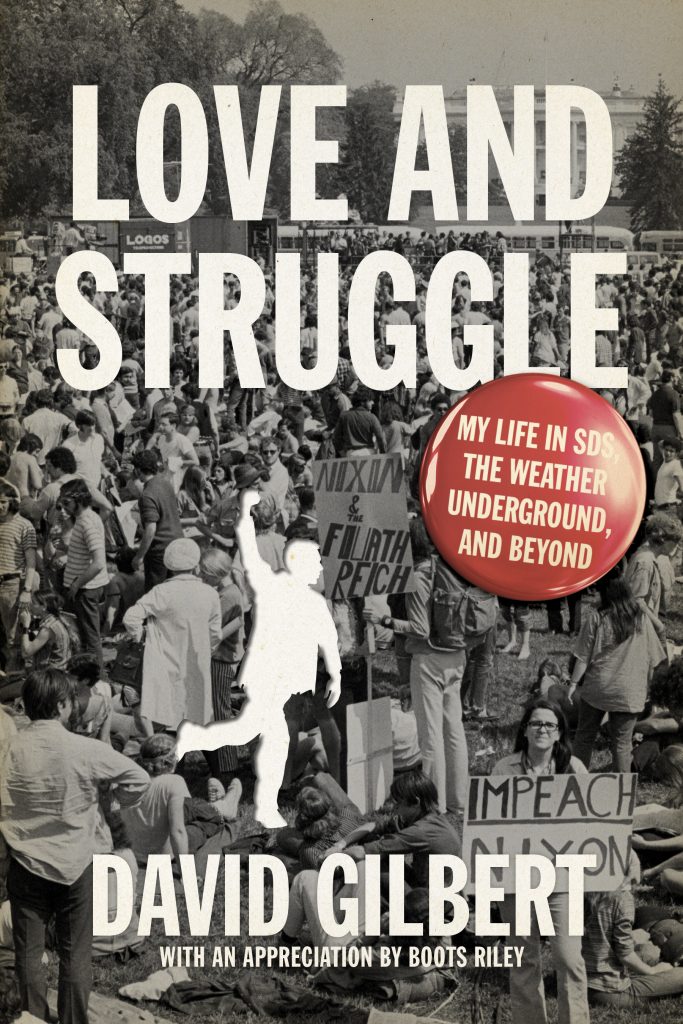

David was a founding member of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), and when the group split into different ideological factions in 1969 he became a Weatherman (later the Weather Underground Organization). He spent more than ten years underground before being captured in an armed action with the Black Liberation Army in 1981. And that’s about all I knew when I started writing to him.

With prisoners, that awkward “getting to know you” phase becomes an even more self-conscious and frustrating process than usual. Letters in both directions are torn open, read, even confiscated or destroyed by prison mailroom censors. Visits are too brief and too infrequent, always under the looming presence of armed guards. There are questions I’m not sure if I should ask, and details he may feel too closely watched to share.

Despite it all, through it all, David has been a tremendously gifted communicator. His letters burst with life and passion, and his quirky, sometimes painfully nerdy, sort of humor. He is so real and so charming in those pages that he breaks down some of the barriers between us—the walls, the razor wire, the hundreds of miles, the years. He is warm in the coldest of environments. He asks about my mother and jokes about my cats. He asks if I’m taking care of myself.

David’s contributions to the Certain Days: Freedom for Political Prisoners Calendar and other publications demonstrate his ongoing commitment to building a better world and fostering stronger movements. He is constantly reading, thinking, probing. He wants to know where things went wrong and what we can do better. In our political discussions he is a seemingly inexhaustible source of inspiration and mentorship. Yet these are slow conversations, drawn out over months and years. Working on a variety of projects together, we are often more concerned with the task at hand than delving into the details of his own political development and life outside of prison.

To fill in blanks, I pieced together some of David’s history and ideals from pamphlets and web pages—they painted him as a murderous criminal, a martyr, and everything in between. Years ago I spent a whole afternoon staring at his mug shot, his face beaten and bruised almost beyond recognition. I wondered what had led him to that moment, and what those torturous first days after arrest were like.

In 2004 he released No Surrender, a collection of his prison writings. I read it ravenously, thrilled to have more insight into his story and the trajectory of his thinking over the years. It covered his trial statements, struggles against white supremacy and male supremacy, AIDS work behind bars, musings on international popular movements, and even several humor pieces and children’s stories that he wrote for his young son.

Many of the insights in these collected writings are invaluable. For David, there is a lesson in everything, and he practices self-criticism more actively and honestly than anyone I’ve ever encountered. For a whole new generation facing repression for our own activism, these articles help us learn from both the failures and successes of the movements that came before us.

Yet it still felt like there were so many things, even after all those years and writings, that I didn’t know about David’s story. And I wasn’t alone. His son, Chesa, now an accomplished scholar, put it bluntly: “Honestly, Dad, I’m not enthusiastic about No Surrender. I mean, you have some good stuff there, but it’s almost all analytical. People relate much better to personal experiences. I wish you’d write about yours, about what life in prison is like” (6).

With Love and Struggle David finally begins to open a more personal side of himself up to us. In his typically humble fashion, he resisted telling his life story for many years. “I always said I wanted to live my life rather than write about it, and memoir as a form always felt too self-involved, and often too self-justifying, for me,” he explains in his introduction (7).

But Chesa was right; in adding more of the personal to his writings, the political message becomes even more powerful. In a series of vignettes David takes us through some of the key moments in his life as an activist. I finally get a more complete picture of his brutal arrest and what led to it:

Surprising that they’re hitting me in the face too. Aren’t they worried about visible signs of the beating? Are they so enraged that they’re not thinking? Or do they feel that the car crash that ended the chase gives them cover for any bruises?…It’s October 20, 1981. The little drama of my “interrogation” follows the much bigger one of a Brink’s armored car robbery that went terribly wrong: Unexpected gunshots at the scene; someone who just happens to be looking out a rear window at an otherwise deserted and obscure spot sees the sloppy switch of vehicles; the escape truck gets caught at a red light, by the entrance to the NY Thruway, as police come to set up a roadblock; a shootout; a car chase on unfamiliar streets; a crash, relatively mild but enough to stop the car, as our Honda can’t quite negotiate a sudden right-angle turn. Maybe at that point revolutionary ideals call for a shootout, but I don’t have a gun and wouldn’t be effective if I did. So it is capture instead. (11)

David describes the long night of interrogation, beatings, and threats in vivid detail. But as always, he offers a lesson: “As tense as things are, I’m spared any anxiety at all about whether to talk. That’s a bedrock principle, one based on the reality that, however bad a situation is, ratting throws others into the same cauldron. So my focus is on bobbing and weaving—physically and psychologically—trying to minimize the damage I sustain. It’s not even defiance or resolve; it’s just that talking is never even an option that enters into my mind” (13). David’s lack of bravado but steadfastness in such a terrifying situation sets an example for activists who continue to face arrests and interrogations—many less harsh than what he endured.

“How the hell did I end up in such dire straights?” he asks, and with that returns to the starting point of his journey, weaving the tale through his comfortable childhood in upper middle-class Brookline, Massachusetts, awakening to the reality of racism through Martin Luther King, Jr., the lunch counter sit-ins in North Carolina, years as a student organizer at Columbia University during the 1960s, anti-racist work with white working class youth, resistance against the war in Vietnam, split from SDS to become part of Weather, and life underground. Throughout it all David shares his thought process as he transforms from a liberal to a revolutionary.

On February 18, 1965, Malcolm spoke to a capacity audience in the Barnard gymnasium. I was there, although with mixed feelings. I felt favorably toward him because I supported Black militancy, but his nationalism made me uneasy—would I be rejected just because I was white? What role did we have in the struggle?

It is rare that a mere speech has lasting impact on one’s consciousness. But seeing Malcolm speak was one of the formative experiences of my life. I had never encountered such a clear exposition of social reality. He explained that the division in the world wasn’t between Black and white but rather the oppressed, who were mostly people of color, and the oppressors who were mostly white. He also put forward a positive role for whites—but not within the Black struggle. Our role was to fight the system and organize within our own communities. Three days later, he was dead. (28)

David also traces the development of his anti-sexist analysis, beginning with an honest accounting of the damage he inflicted on others while racking up sexual conquests in the era of free love: “My scoring mentality ended up hurting people in situations where they were emotionally vulnerable. In retrospect, given the era, I can understand the context for my cavalier attitudes—but it is still hard to accept that the hurt on Corrine’s face didn’t break through my male conditioning. And not incidentally, her subsequent need to avoid me meant that the Vietnam Committee lost a valuable member” (53).

Beyond David’s candor, he also looks more broadly at the ways in which sexism weakened the entire movement: “Anti-imperialist men, with our crass sexism, have a major share of the responsibility for this setback of historic proportions: the failure at that time to forge a strong alliance and synergy between anti-imperialism and feminism. Such an alliance would have made both sides’ politics more revolutionary and humane, with the Left developing a fuller program around women, and feminists becoming a major force to move an oppressed sector of whites toward anti-racism” (60–61).

David’s political development continued at a breakneck pace as the war intensified both abroad and in America’s cities:

It was the most insane of times; it was the most sane of times. Those nine months, from the split of SDS (June 8, 1969) to the tragic townhouse explosion where three bright and idealistic but badly off-course activists were killed (March 6, 1970), were the most frenetic, transforming, and out-of-kilter months imaginable….

How can I say that it was also the most sane of times? The sad reality is that the status quo, the day-to-day comfort, the conventional wisdom of empire is insanely anti-human. True human sanity does not consist of remaining calm, cool, collected—going on with life as usual—while the government murders Black activists, carpet-bombs Vietnam, trains torturers to “disappear” trade-union organizers in Latin America, and enforces the global economics of hunger on Africa. (121–22)

David’s recollections of life underground in Denver are riveting and probably the strongest in the book in terms of narrative writing: all-night self-criticism sessions, awkward orgies, fighting cops in the streets, headline-grabbing actions, close calls, and attempted infiltrations. It’s almost hard to believe, in the same way that it’s hard to grasp how close the possibility of “revolution in our lifetime” was during that explosive era. There are lessons here too—but David seems to relax into the storytelling a bit more, and it’s an effective shift.

He says few words about his relationship with Kathy Boudin, but their mutual love for their son is evident in one of the most poignant sections of the book, detailing the challenges and joys of having a baby in such a precarious situation. The moment when they must leave him with friends to serve their prison sentences is heartbreaking, and a reminder of the very real sacrifices these men and women made in order to resist imperialism.

With this book David has given us a gift with many layers to explore, though he has yet to satisfy his son Chesa’s request to write about life in prison. There are thirty more years of the story we’re still waiting to hear, and beyond.