By Diana Leafe Christian

http://www.ecovillagenews.org

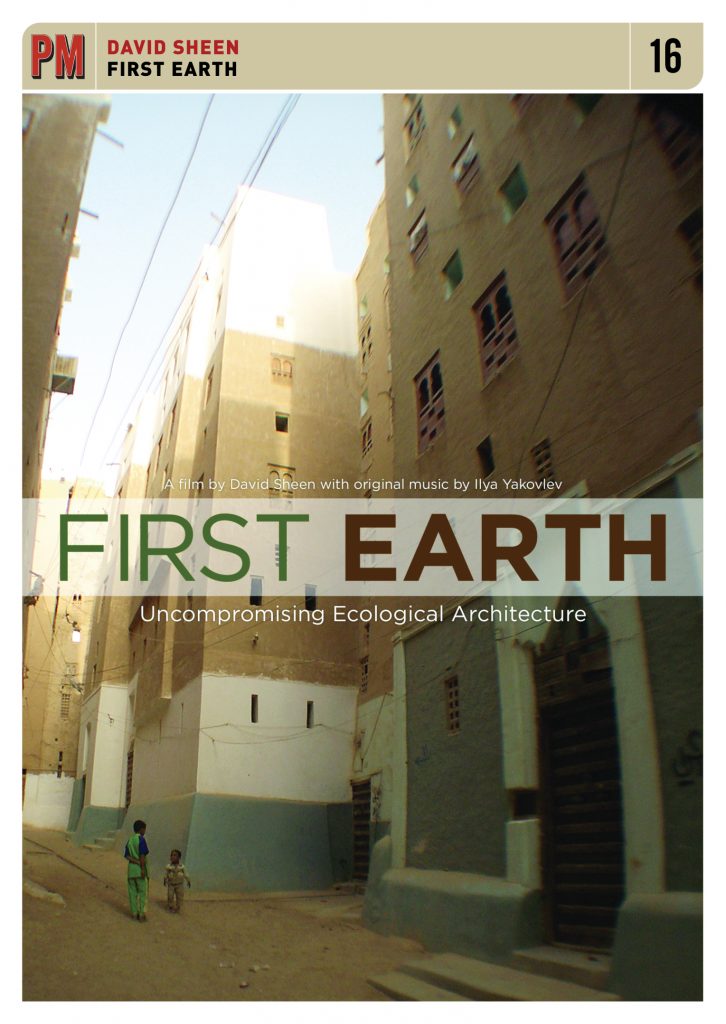

First Earth: Uncompromising Ecological Architecture,

by filmmaker David Sheen, knocked my socks off. A “why-to,” not a

“how-to,” this evocative and beautiful documentary shows why building

with earth — cob, straw clay, adobe bricks, rammed earth — works well

structurally, lasts a long time, compels the eye and heart, is healthier

for builders and dwellers than most other construction methods, and

feels good to live in. And can even spiritually uplift and inspire the

builders.

Filmed on location over four years on four continents,

First Earth features curving art-poem dwellings in the Pacific Northwest

in Canada and the US; thousand-year-old apartment-and-ladder

architecture of Taos Pueblo; centuries-old and contemporary cob homes in

England; classic round thatched huts in West Africa; bamboo-and-cob

structures now on the rise in Thailand; and soaring Moorish-style

earthen skyscrapers in Yemen. It engages the left brain as well, with

brief appearances by renowned cultural observers and activists (Derrick

Jensen, Daniel Quinn, James Howard Kunstler, Richard Heinberg, Starhawk,

Chellis Glendinning, and Mark Lakeman, among others) speaking on what’s

not right with our society and how building with earth addresses some

of these ills, and major natural building teachers (Michael G. Smith,

Becky Bee, Joseph Kennedy, Sunray Kelly, Janell Kapoor, Elke Cole, Ianto

Evans, Bob Theis, and Stuart Cowan, among others).

”Earthen Buildings Are Best”

The

film proposes that earthen homes are the healthiest housing in the

world, while stick-framed housing and conventional buildings are

soulless rectilinear sources of resource depletion and pollution. That

curvilinear buildings elevate the spirit and cultivate the heart. And

further, that since it takes a village to raise a child, one of the best

things we can do for humankind and the natural world is to transform

suburban sprawl into cozy, curvy earthen ecovillages. “In the age of

environmental and economic collapse, peak oil and other converging

emergencies,” writes David Sheen on his First Earth website, “the

solution to many of our ills might just be getting back to basics,

focusing on food, clothes, and shelter. We need to think differently

about house and home, for material and for spiritual reasons, both the

personal and the political.”

David Sheen, whom I had the pleasure

of meeting and visiting with for a day recently, is a lively and

stimulating young Renaissance man (check out his Anarchitecture

website), who started out as a designer and graphic designer. (As I

watched First Earth I thought, “Oooh, this is how a film looks when it’s

put together by a graphic designer. All filmmakers first should be

graphic designers!” )

David began studying, designing, building,

and filming natural buildings in 2001. He apprenticed with natural

building masters Ianto Evans and Linda Smiley at the North American

School of Natural Building in Oregon, and Michael G. Smith at Emerald

Earth Community in Northern California. He studied biomimicry, the study

of nature’s design principles and its application to human habitats,

with renowned architect/designer Eugene Tsui. Born and raised in

Toronto, David lived for several months in urban and rural intentional

communities in the US, and for the last three years in kibbutzim in the

south of Israel.

But Is This Always True?

I loved the film and recommend it highly. Yet I disagree with its premise.

Another traditional earthen building in Africa.

For

example, one of my friends at Earthaven Ecovillage, where I live, is

building a 12’ x 12’ x 12’ stick-built, shed-roofed dwelling with wood,

and concrete, rebar, R-Foil building wrap, recycled cellulose

insulation, and earth-plastered walls inside and out. As a rectilinear

hybrid structure built mostly of wood, you could argue, based on the

film’s premises, that it’s a soulless box whose materials and

construction method harm the Earth. But is it really? The 2x6s were

felled by the builder himself from onsite trees to clear fields for an

organic farm, and milled less than five miles away in a sustainable

sawmill. As a hybrid building, with both conventional and natural

building materials, it’s contributing less pollution than a

conventionally built building of the same size. As a passive-solar

building, it has a slab-on-grade poured concrete floor (insulated

against any winter cold from the Earth) and poured concrete countertops —

both for thermal mass — and radiant floor heating for back-up.

It’s

tiny, because my friend wants a simple unpretentious home that doesn’t

cost a bundle or take long to build — given that construction time

equals money. It’s mostly rectilinear because this shape is much cheaper

to build in terms of labor and time than curving shapes, whether of

wood or earth. Natural building is not necessarily cheaper than

conventional building, contrary to popular belief. If you take into

account the amount of labor time, which means either the owner-builder

is taking off work (which costs the builder) or hiring labor or housing

and feeding work-exchangers, it all adds up. The same friend built a

similar 12’ x 12’ x 12’ home a few years ago in another part of the

community, mostly by himself, and only on weekends and evenings after

work. It cost him $8,000 in materials and about $8,000 in labor at his

then-current rate if he had charged for it. (Another friend in another

community is building a beautiful two-story, one-bedroom cob, strawbale,

and adobe-brick home. Mostly because of labor, his construction costs

are estimated to be almost $300,000 by the time it’s finished.)

My

friend is also building tiny, square, and cheap so he can minimize the

energy he puts into his own home so he can get on with what ’’else’’ he

does at Earthaven — operating a business which provides a needed onsite

service and employs other members who need jobs; operating a small farm,

which produces food and other products for the community (and in the

future will employ others); and focalizing the new alcohol co-op. (See

Will Earthaven Become a “Magical Appalachian Machu Picchu”?) He’s not

putting much energy, time, and money into building the kind of beautiful

home the film advocates because he’s putting it into building the

community itself.

So this is why the idea that building with

earth, and curvilinearly, is the ecologically sustainable way to build

(“uncompromising!”) does not convince me. David and I talked about this

briefly, and he gets it, of course. He knows the film paints a complex

subject with overly broad brush strokes to make a point. And it does,

beautifully.