By David Gilbert

Open Democracy.net/Transformation

December 26th, 2014

From Weather Underground activist to life in prison

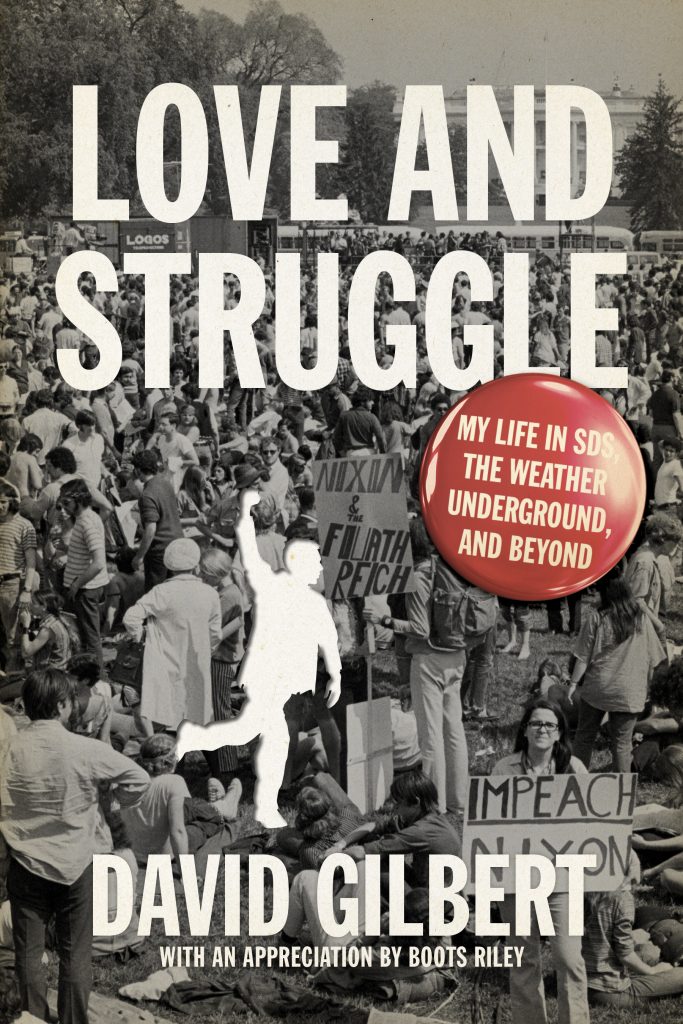

Even in a just war we need to feel the pain and tragedy of losses on the other side. And in the Brink’s robbery our own mistakes and failings led to unnecessary casualties. An extract from Love and Struggle: my life in SDS, the Weather Underground and Beyond.

David Gilbert is a former member of the Weather Underground Organization, currently serving a prison sentence of 75 years to life for his role as a getaway driver in the robbery of a Brink’s armored car on October 20, 1981. The robbery, carried out by members of the Black Liberation Army with the May 19 Coalition, led to the deaths of two police officers and a Brink’s guard. At the trial Gilbert, along with Judith Clark and Kuwasi Balagoon, represented themselves as anti-racist freedom fighters involved in a necessary struggle against US imperialism, and refused to recognise the authority of the court to try them.

David Gilbert at the Colombia University strike against war and racism, 1968. Credit: Love and Struggle/PM Press.

“Mr. Gilbert, do you understand now?”

“Yes, Judge Ritter, I understand you. You know, the plantation owners used to sit on their verandas, sipping mint juleps, complaining about how lazy the slaves were. The U.S. Government, which broke virtually every treaty it ever signed with Native American nations, coined the term ‘Indian giver.’ The same people who stole the northern half of Mexico claim that all Mexicans are thieves. In that tradition, your ruling makes perfect sense to me.”

Looking back at my own series of court statements, they seem to become progressively more rhetorical and hardened as time went on. My sentencing speech in particular spilled over from healthy defiance to crass insensitivity.

Trying to show that life sentences didn’t deter revolutionaries, I declared that the issues that motivated us to fight—the depth of racism in the US and the millions of people killed each year by the economies and wars imposed by imperialism—were much larger than three lives. I meant the three of us facing life in prison. (Because I included Mtayari [Sundiata], who was killed three days later, I thought of the this confrontation as having cost four lives.)

But when I said “three lives,” I caught a glimpse of a woman in the court who flinched as if I had struck her. Only later did it dawn on me that she was a relative of one of the men killed on October 20, thinking, feeling, that those three lives were the ones I was dismissing so cavalierly.

How could I have become so insensitive? I, at one time a pacifist, had come to ally with national liberation movements under fire. Not only were New Afrikans engaged in a just struggle, but it was a war that had been forced upon them by the murderous assaults on legal dissent, while so much of the white Left looked on passively.

The Black Liberation Army (BLA) never shot anyone who wasn’t an armed professional and always took great care to avoid civilian casualties—a far cry from government forces who killed civilians on a grand scale and later came up with the dehumanizing euphemism of “collateral damage.”

Yet, even in a just war, as the Vietnamese had showed us, we need to feel the pain and tragedy of losses on the other side. And in this particular encounter our own mistakes and failings had led to unnecessary casualties.

Even though the government’s aggression was the source of the conflict, these particular individuals working as enforcers of the rule of capital didn’t at all see themselves in a warfare situation. If I had been more of a revolutionary, more fully rooted in humanism and less anxious to show my mettle, I would have expressed, in addition to my commitment to the struggle, sadness and regrets about the lives lost and the families shattered.

We became more embattled as the two years of court confrontations progressed. Three basic issues led to our being removed or, more often, our walking out. One was the treatment of our supporters, such as the attack on Ahmed Obafemi…who had been very visible as NAPO’s [New Afrikans Peoples’ Organization] main public spokesperson around our case and was seated right by the aisle. When the judge entered, and our people did not rise to honor him, the sheriffs immediately pounced on Ahmed, hitting him with clubs. When three nearby friends tried to protect him, all four were dragged out and arrested.

The worst incident was life-threatening. A carload of people, two adults and three children, barely avoided a serious accident when the front wheel came loose as they were returning home from a visit with us. When they took the car to a mechanic, he said that someone had removed a cotter pin. Since there was no problem on the way up, it had to have been done in the jail’s parking lot.

Our major frustration in terms of the conduct of the trial was the way we were consistently blocked from discussing racism. We weren’t allowed to conduct a searching inquiry of potential jurors for bias; we were stopped every time we tried to present the situation of New Afrikans and other people of color within the US; discussion of relevant international law was forbidden; and we were blocked from bringing up COINTELPRO and other well-documented illegal government programs that had driven previously nonviolent activists into underground resistance.

Our most telling obstacle was our inability to have the legal meetings needed to prepare our defense. When the court was in session, the only time we could meet was at night. Orange County Jail, which had previously allowed nighttime legal meetings, changed the rules to prohibit them.

…

Given the cotter pin incident and other threats to our supporters, which we had described to the judge for the record in court, this public release of personal information was a chilling effort at intimidation. The lack of meetings and preparation, more than any other issue, occasioned our walkouts and boycotts.

We spent most of the trial in holding pens underneath the courtroom, in three separate cells, surrounded by law enforcement personnel. There was no one in the courtroom representing us, and the proceedings were piped in via a speaker. We were told that at any point we could return to the courtroom as long as we promised not to be “disruptive”—in other words, insist on talking about forbidden topics.

The drone of the speaker, amid the buzz of a swarm of hostile guards, as the link to the pomp and pretense of the court was all a bit surreal. Going to the bathroom became truly bizarre. I (or Kuwasi or Judy) would be chained hand and foot and taken to a large room with a toilet on a raised platform in the middle to pee while still chained and closely watched by five guards.

At one point I could make out from the speaker some testimony by an FBI lab technician, who said that glass particles had been found in my clothing that could only have come from the windshield of the Brink’s truck. I was astonished because the prosecution knew full well that I’d never been within a mile of the truck. For a moment I had an impulse to go back upstairs to contest this fraudulent “evidence.” But what could I say to refute this highly credentialed FBI technician? And what good would it do?

…

Such tactics dovetailed with a systematic media campaign to dehumanize us. The Black comrades were always portrayed as thugs—despite the reality that Kuwasi’s and Sekou’s histories were fully and deeply political. The media didn’t mention that they had been part of the Panther 21 case—who could have more justification for moving into clandestine forms of struggle?

The white defendants, who had attended elite universities, weren’t depicted as thugs but instead as psychopaths—a standard method going back at least to John Brown of discrediting whites “crazy” enough to throw their lot in with people of color. These portrayals were visually reinforced with the artists’ sketches of us in court (no cameras were allowed). Even the Correctional Officers commented that in person we didn’t look anything like those newspaper portraits.

…

How could I—with so much experience that taught that clandestine work can only be built on the basis of full political and strategic understanding—have allied on such a high-risk tactical level with so little knowledge of the political context?

The answer lay in my own form of corruption. Drugs and money had no allure for me, but ego did. Especially after the collapse of the Weather Underground Organization, I was anxious to reestablish myself as a “revolutionary on the highest level,” as “the most anti-racist white activist.”

What better way to validate myself in this way then to work closely with the most revolutionary Black group going? If the political and strategic terms weren’t clear to me, I would quietly make myself useful until trust and a higher level relationship developed.

Not only is this a terribly wrong way to build solidarity, but also the “exceptional white person” mentality usually undermines any serious effort to organize other people against racism—a fundamental aspect of developing solidarity and working toward revolution. When some friends told me that this unit of the BLA had “used” me as a resource, my reply was that I had used them as well, to be my source of validation.

The recognition, under these difficult life circumstances, of my corruption of ego did not prove shattering to my core beliefs and commitments. I had observed many times how movement leaders, who started with the most idealistic motives and who had taken great personal risks, later got blindsided by their egos. While it’s much easier to see such behavior in others, why should I be exempt? Each of us is raised in this society.

I couldn’t expect to simply anoint myself a “good guy” and miraculously be 100 percent pure from then on. What was required instead—the essential challenge of being a revolutionary—was an honest, ongoing process that involved both serious introspection and constructive collective discussions. It’s not like we’re adrift on a featureless, turbulent sea. We’re deeply rooted in the solid ground of the needs and aspirations of the oppressed.

This extract is reproduced with permission from PM Press. All rights reserved. Copies of Love and Struggle: my life in SDS, the Weather Underground and Beyond are available for purchase in hard copy and as an e-Book.