By Ernesto Aguilar

Political Affairs Magazine

From

the moment Marxists and anarchists parted ways in 1872, the peculiar

and occasionally rancorous tension between the divergent schools of

socialism has been the subject of many a debate, study group and

protest. For anarchists, as Mikhail Bakunin articulated, Marxism’s

ascension would virtually necessitate it would become as oppressive as

the capitalist state. For Marxists, anarchism’s impulse to support no

one having power meant the well-connected in-crowd, mostly well-heeled

and white, would exert their power in other ways and with the tacit

support of the core of the people. From these early conflicts came years

of characterizations – as often fair as misguided – of a host of

Anarchism’s motivations and political aspirations, and about organizing

and the lack thereof.

Still, it would be a sin of omission

to avoid saying there was not at least a hint of admiration at times on

the part of Marxists for anarchism’s flair for harnessing the creative

energies of youth, or by anarchists, who secretly desired to have the

credibility to organize broadly, with clarity and among communities of

color. The admiration is spotty though. Marxism and anarchism have

historically had a love-hate relationship as impassioned and tragic as

anything Euripides ever penned.

Anti-globalization currents,

and both tendencies’ struggles to turn early protests into a massive

anti-capitalist mobilization, have rekindled discussions of the kind

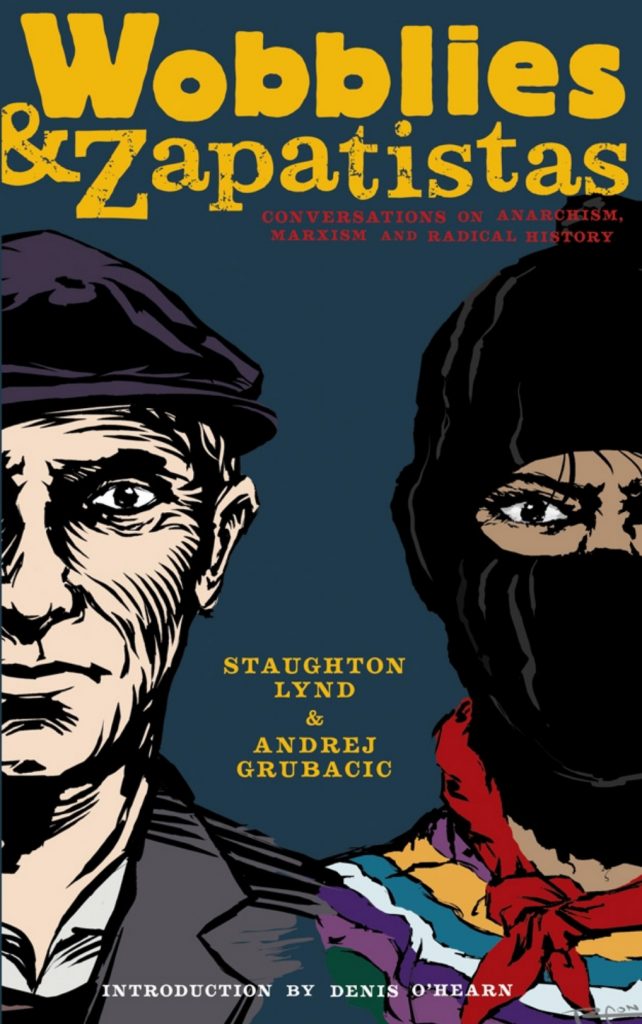

found in Wobblies and Zapatistas: Conversations on Anarchism, Marxism

and Radical History. Granted, few of these dialogues have involved

luminaries of Staughton Lynd’s stature, yet they represent a starting

place – not only about differences, but also about commonalities, shared

values, and hopes for a better world.

Wobblies and

Zapatistas puts Lynd at the table with Andrej Grubacic, a Northern

California anarchist by way of the Balkans, for extensive exchanges

about history, political theory and practical reality. Removed from

these talks are some of the stranger hues of Marxism and anarchism –

extreme sectarianism and “post left” posturing among them – nor is this

book intended to blast one idea or the other. Instead, Lynd and Grubacic

are aiming squarely for those looking to build bridges between the two

camps.

Their conversation about the Zapatistas’ militancy

emerges an intriguing discourse, flowing throughout the book, about how

politics over the last generation has fundamentally changed. For this

reason, how activists and radical partisans in the struggle see

themselves and their orientations must also change, with an eye to

rejecting old labels. This is not a new revelation. The New Left has

postulated such ideas for some time, and the aforementioned

anti-globalization clashes and demonstrations have often eschewed

ideological tags. In Lynd and Grubacic’s estimation, internationalism is

as much of the heart as it is about politics. One could derisively call

this misty idealism, although one cannot discount the earnestness of

such beliefs.

Both are correct in seeing the importance of

“big-picture” ideas when it comes to putting forward a political vision.

For example, proclaiming that Joe Hill would have seen himself as a

Palestinian conjures up effective imagery, and a fertile discussion

arises from this point. Lynd seems to acknowledge the amount of work

that remains to be done when he argues that the movements of today face

difficulties concerning strategy. Compare this with the South’s fight

over African American disenfranchisement and the North’s battle against

the war in Vietnam in the 1960s-70s, which galvanized disparate forces.

Yet, the bulk of the book suggests a bigger problem is the reliance on

old ways of doing thins. What gets a little downplayed here is an

assessment of the amount of work involved in moving towards these

“big-picture” moments.

Lynd’s remark that anarchism and

Marxism are not mutually exclusive alternatives, but Hegelian moments

split by personality clashes with the First International, seem

simplistic, and comments in the book too often dismissively reduce

significant and substantive splits to mere sleights of hand. At the same

time, engaging critiques, such as seeing anti-imperialism not as a

rejection of everything American but as embracing the best in American

radical traditions, abound. Reexaminations of the Haymarket affair and

the Industrial Workers of the World (“the Zapatistas of yesteryear,” as

Lynd calls them) are sure to make one look upon these memorable

revolutionary surges in a new light. Chalk that up to Lynd’s take on

history, which is richly textured and buoyed by the weight of

experience.

One cannot address the ideas presented here

without appreciating Lynd’s remarkable life. From his expulsion from the

military to his directorship of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating

Committee’s Freedom Schools, to his engagement in the Youngstown steel

mill struggle in the 1970s and beyond, Lynd has been a critical figure

on the left. He has also been a vibrant socialist, albeit one who has

embraced socialism’s diversity over dogmatism. His genuine love for

humanity shines through, and it is doubtful such a that this dialogue

could be so arresting without his compassion.

Noted German

statesman Otto von Bismarck was famously quoted as saying after the

First International split that “crowned heads, wealth and privilege may

well tremble should ever again the black and red unite.” In the pages of

Wobblies and Zapatistas, such a possibility seems not so far away.

Back to Denis O’Hearn’s Author Page | Back to Staughton Lynd’s Author Page | Back to Andrej Grubacic’s Author Page