by Eric Stanley

The Abolitionist, Critical Resistance’s paper

ericstanley.net

November 29th, 2012

Born at the end of the long 1970s, I often find myself looking toward that decade with a somewhat politically dangerous sense of attachment. I cannot help but be endlessly inspired by the numerous anti-colonial and Black liberation struggles, the women’s and gay liberation movements, and the massive student and prisoner organizing of that period of history.

Living now, in what feels like an extended lull in radical politics in the US (even with the Decolonize/Occupy movements both flourishing and conceding), its hard not to nostalgically long to know what it might feel like to fight against empire as a part of a international and truly massive movement. This is not to suggest that this work, or our collective dreams for another world have vanished. Many of us do continue to organize and rewrite those traditions within our narratives of today. However, the raw power and urgency often articulated by those that lived these years seems to have been evacuated in the present and replaced by more protracted visions and constricted possibilities. The revolution that many believed was “right around the corner” has yet to come, or perhaps it is on the way, just much slower, and in a different form than was once thought.

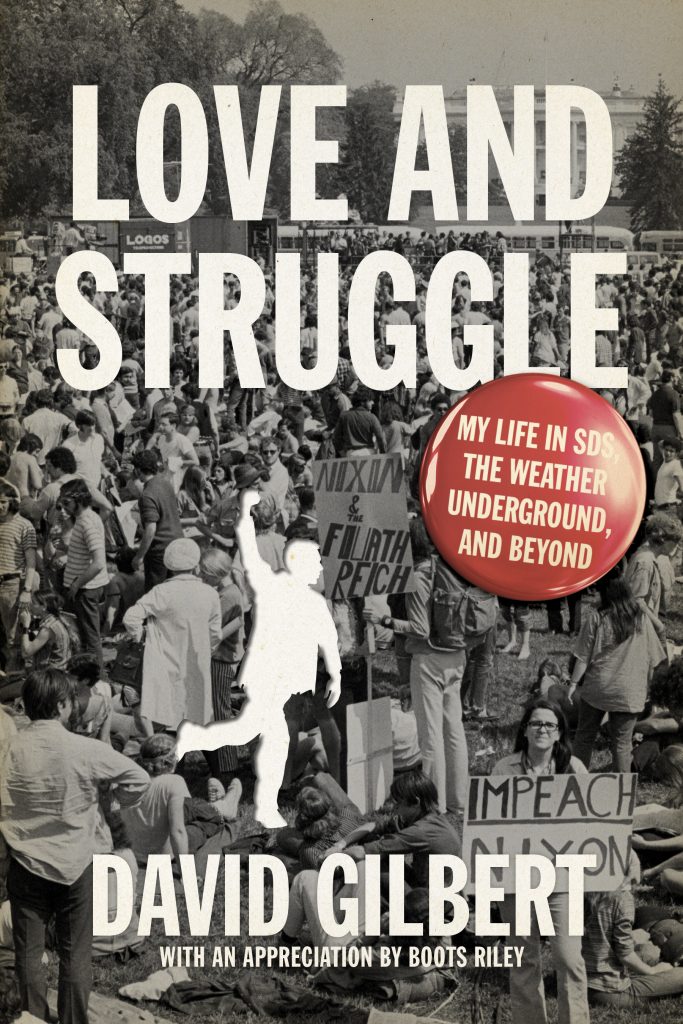

Longing for another era is of course much easier than living in that time. But luckily we have records of this collective history, which can inform how we struggle differently today. David Gilbert’s new autobiography, Love and Struggle: My Life in SDS, the Weather Underground and Beyond (PM Press) offers not only a chronology of those explosive years, but also, and more importantly, he carves a personal, and often times emotional account of the wins and the many losses of those years. Gilbert, possibly more than most others who have written about that era from the inside, offers a necessary and productive foil to my naïve understanding.

From his jail cell at the Auburn Correctional Facility in upstate New York, Gilbert begins his story with his youth in the suburbs of Boston, MA. Looking back, he gleans his own history for traces of what and when his otherwise white middle-class upbringing was transformed into a commitment to undoing systematic oppression. He attempts to understand his own political growth—beginning at the ends of the Civil Rights era to his arrival as an undergraduate at Columbia University in New York City as the war against Vietnam began to escalate. The book follows his life from aboveground community organizer to underground freedom fighter and ends with his eventual imprisonment in 1981.

In the chapter “ The 1960s and the Making of A Revolutionary” Gilbert details his early college years where his activism and analysis intensified. In 1962 he joined CORE (Congress on Racial Equality) and then began working with the Columbia chapter of Students of a Democratic Society (SDS), a group which organized primarily on college campuses against the Vietnam War. He states, “My turning point from ardent protest to throwing my whole life into stopping the war can be marked with an issue of Ramparts.” (45) unlike other alternative media of the day, Ramparts included full color photographs of Vietnamese children burned by napalm. He cites the “emotional impact” of those photos to be the lever that propelled him into a full-time organizer.

While both his personal history and the political sketch he offers are well articulated and important, I find the tone of his writing to be a vital intervention into the otherwise austere way the history of the US radical Left gets retold. This tone is supported by a deep commitment to self-reflexivity as he continually mines for missteps in his, and our, history. For example, rather then concluding his analysis with some compulsory comments on the category “women”, Gilbert offers a powerful critique of the ways the left helped produce a culture of misogyny that, like the larger world they were resisting, silenced women, reproduced the gender binary, and protected a kind of middle-class whiteness. Importantly, he undoes the often-used alibi that these practices were simply “symptoms of their time” he works to unpack how and why sexism was so ubiquitous, including his own active and passive participation in it.

And while he does offer some thoughts on queer liberation, this thread could be developed further, especially in relation to his co-defendant in the Brink’s case and long time friend Kuwasi Balagoon, who was arguable “queer” and died in prison a few years after their capture from AIDS related causes.

Another crucial moment in the radicalization of Gilbert, or at least an event that would eventually alter his life, was the infamous split that happened at the national SDS convention held in Chicago in June of 1969. While the intricacies of the split are both well documented and contingent upon who is offering that documentation, in short the split indexed a larger tension in the US, white student left between an analysis that suggest class was the major factor in oppression which was supported by Progressive Labor, and on the other side was the Revolutionary Youth Movement who argued that class cannot be understood without an analysis of racism and sexism (this antagonism still figures forcefully today). The convention ended with the walkout of many delegates instigated by, among others, Bernadine Dohrn.

This split lead to the creation of the Weathermen, later renamed the Weather Underground, a clandestine organization dedicated to militant direct action, namely bombing building—with precautions to not harm anyone—as a way to expose the violence of US imperialism both here and around the world. Reluctant at first, Gilbert eventually joined a Weather collective and headed underground.

While many others have written about living underground and of the Weather Underground in particular Gilbert’s account brilliantly oscillates between the intensity of living underground—evading police, obtaining and using fake IDs, building bombs, and then the monotony of everyday life—trying to find under the table work, months of planning for a single action and perhaps most vividly; the isolation from being cut off from your former life. While Gilbert offers insight on how power worked “inside” the underground, he writes with what I see with a deep sense of ambivalence. Not a political ambivalence, but with an honest and retrospective analysis of what it felt like to live underground. The affective dimensions of the book also offer us much for thinking about the necessity of care, which was then, as it often is now, discredited as “counter-revolutionary.”

“It is precisely because of our love of life, because we revel in the human spirit, that we became freedom fighters against this racist and deadly imperialist system” Theses words are from Gilbert’s’ statement in court on September 13,1982 after he had been arrested and charged in connection with the Brink’s truck robbery, an attempted expropriation done in solidarity with the Black Liberation Army, which eventually lead to his imprisonment. They encapsulate the spirit of his moving account of the pleasure and terrors of living a revolutionary life under the powers of a state that is intent on liquidating resistance at all costs. While Gilbert’s details of the Weather Underground and SDS fills in many of the gaps in those histories, his political commitment in offering us a tool for today is what makes Gilbert’s book necessary for all of us invested in structural change. Even after serving over 30 years as a political prisoner, Gilbert writes with humility, clarity, affection, and even humor, as he reminds us that care—care for each other and for our movements— produces as much, if not more, radical potentiality than a bomb. Revolutionary struggle, yes, but love too, love and struggle, indeed.