By Cynthia Kaufman

People all around the world are working to build solidarity economies, based on worker-owned collectives, the creation of local currencies, and making one’s own things and sharing them. Advocates of a solidarity economy claim that, as we build more of these kinds of economic relations, we will also build more satisfying lives and have a less negative impact on the environment.

But unless we work on taking down the old as we build the new, this work will be constantly thwarted by the control that those old systems have on our economies, the impact they have on our environment, and the power they hold over our imaginations. And unless we can explain how a transition to a solidarity economy won’t, in the short term, lead to unemployment and poverty, it will be hard to build significant support for such a change.

We need to be able to explain how it is that, as we build new economies, we will not run afoul of what I call the “economic dependency trap of capitalism”—that once you have a large capitalist sector, people’s well-being does become dependent upon capitalists offering them jobs. Projects and policies that interfere with business as usual can result in companies closing and jobs being lost, and real suffering for the people who depend on those jobs.

Freeing Ourselves from the Economic Dependency Trap

In order to lessen the economic dependency trap of capitalism and build support for a move toward a solidarity economy we need to:

1. Promote the use of alternative economic indicators.

If people are told every day in the news that the cause of their poverty is a lack of economic growth, they will support pro-growth policies. We need to help people distinguish what is good for social well-being from what is good for capitalist growth. One important way to wean people off growth is to promote the use of better economic indicators. Sometimes growth leads to more jobs and sometimes it doesn’t. But increases in well-being are always good. If we measure an economy based on things directly associated with well-being–like literacy, longevity, and reported happiness—then we will be able to figure out which policies are good for our economy, and distinguish them from policies that increase capitalist economic activity but may not improve well-being.

· The states of Maryland and Vermont now both track their social progress using Genuine Progress Indicators (GPI). Use of the GPI in Maryland, beginning in 2009, helped influence decisions to increase spending on community colleges and to raise the state minimum wage.

2. Strengthen social safety nets

In countries without strong national health care systems, and other systems of benefits, a full-time job in the formal economy becomes the required path to a secure existence. In countries like Bhutan, where there are strong social bonds that allow people to care for one another, full-time employment is not necessary to obtain this security. Similarly, in strongly social democratic countries, such as Sweden, or socialist countries such as Cuba, it isn’t either, because the state takes care of those things. There is a variety of paths to a social safety net, but lessening the economic dependency trap of capitalism requires that they be developed in some way.

· The Affordable Care Act has allowed millions of people in the United States to break their dependence on the employer for access to health care (see John Miller, “Skew You! WSJ editors are upset that Obamacare makes workers less desperate,” March/April 2014). Now that it is illegal to deny someone health insurance because of a preexisting condition, millions of people with health problems can change jobs without worrying that it will leave them unable to get medical insurance. Imagine the next step, where we had a single-payer insurance system (or “Medicare for All”) and people would not be dependent upon insurance companies to have access to health care.

3. Reduce work time

Struggles for shorter work days can have huge benefits. The move in the industrialized countries to the eight-hour day led to huge improvements in wellbeing. France’s move in 2000 to a 35 hour work week, without a reduction in pay, was a major advance. Shorter work hours have a variety of benefits. The individual spends less time in alienated labor and so has a better life. Also, employers may be forced to hire someone else for the other hours, leading to lower unemployment.

· The state of Delaware passed a policy in 2003 allowing (but not requiring) state workers to reduce their work time. 4. Develop community capital

A community that is under-resourced will go to great lengths to entice companies to locate there, even if the companies offer very little to the community. The mere hope of jobs and maybe a small amount of tax revenue is often enough. But what if governments or local communities had their own capital to invest in socially useful projects? In contrast to finance capital, which is always looking for a short-term return, or venture capital, which is looking for the next big thing to generate huge profits, community-based “patient capital” can be invested in the solidarity economy.

· There are more than 1,000 Community Development Financial Institutions in the United States. Generally, they are non-profit organizations that raise funds to lend out for projects that serve the public good. There are many organizations around the country set up specifically to help finance worker-owned cooperatives; for example, the cooperative Rainbow Grocery in San Francisco runs a coop grant program.

5. Wean ourselves from consumer culture

Given the billions of dollars spent on advertising and on commercial media to promote a high-consumption lifestyle, it isn’t surprising that many people think that the path to happiness is in ever-higher levels of consumption. But if only some people are able to experience those high levels of consumption, the total level of happiness in the society goes down. Empirical studies of happiness, however, find that inequality breeds unhappiness, as people experience status anxiety and as the social fabric becomes torn. High levels of social solidarity and connection are far more important for happiness than high levels of consumption. People need a sense of security, access to food and other basic needs, and a sense of community. Working to challenge the cultural forces that lead people to believe consumption is the path to happiness is an important part of a move to a solidarity economy.

· The size of the average house has doubled in the United States since the 1950, requiring more resources to build, more energy to keep it comfortable, and more stuff to fill it up, and leading to social alienation as family members retreat more into their own private spaces. Small House Style and Living in Small Houses are both web magazines that promote the positive attributes of small houses.

6. Promote equality

If we had completely equal levels of income in the United States today, every family of four would make $200,000 per year. If the two adults in that hypothetical family were to work half time, the family could have $100,000 per year. Similarly, if wages increased by 3% per year, in line with productivity growth, then every twenty-four years we could cut our work time in half, and still have the same incomes we did at the start. That means full-time workers could all make their present salary while working 20 hour weeks. Policies that promote equality include progressive taxation and minimum-wage increases. More effective labor struggles, too, result in a larger percentage of income going to workers.

· All across the country the municipalities are passing $15 minimum wage rates, and workers at low wage jobs are walking out and protesting to demand higher wages.

7. Challenge ruling-class actions

There is no way we can build a solidarity economy on a planet whose atmosphere has been destroyed by the fossil-fuel industry. Similarly, we cannot build a solidarity economy based on institutions like worker-owned cooperatives as long as transnational corporations are able to manipulate governments into supporting policies that favor them.

· Fighting against the Trans-Pacific Partnership and other trade deals that favor the transnational ruling class are crucial for stopping a “race to the bottom” in wages and working conditions.

Conclusion

As long as growth and employment rates are the measures of a healthy economy, our environmental interests will be at war with our economic interests and what is good for capital will be seen as what is good for everyone. We need to wean ourselves off the belief that increased GDP and more work are crucial to improving people’s well-being. But we must also transform society such that it is actually true that building solidarity projects can be a real way for people to meet their needs. For that to happen, solidarity projects need to be part of a broader movement to lessen the economic dependency trap of capitalism and not as utopian islands in a sea of misery.

There are presently social movements working in all of the areas needed to lessen the economic dependency trap of capitalism. I am not arguing here for a new movement, but rather for new ways of understanding the relationships between these movements. If we see the ways that our work is linked, we are more likely to build solidarity. And if we have a clear sense of a path forward, we can be more optimistic that our work can add up to real lasting change. Rather than appearing marginal and utopian, solidarity economy projects can be seen as practical parts of building a new world as we tear down the old.

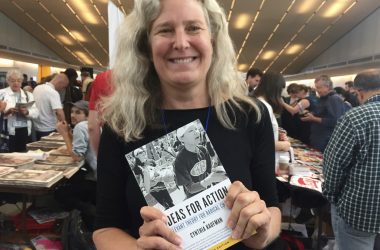

Cynthia Kaufman is the author of Ideas for Action: Relevant Theory for Radical Change, second edition, PM Press June 2016 and Getting Past Capitalism: History,Vision, Hope, Lexington Press, 2012.

This piece originally appeard in Dollars and Sense as a comment

Originally published in Dollars and Sense Magazine

September/October 2015