by Greg King

The Sun

March 2013

The Odyssey Of S. Brian Willson

For

several years during the last decade I gathered inspiration from a

neighbor who often passed by my house on his bike. Actually he rode a

“handcycle” — a tricycle he pedaled with his hands. His legs were gone

below the knees, but with his arms he often cranked out hundreds of

miles a week.

This old neighbor of mine is S. Brian Willson, a

former U.S. Air Force officer. He served in Vietnam, but he didn’t lose

his legs in the war. That happened on American soil.

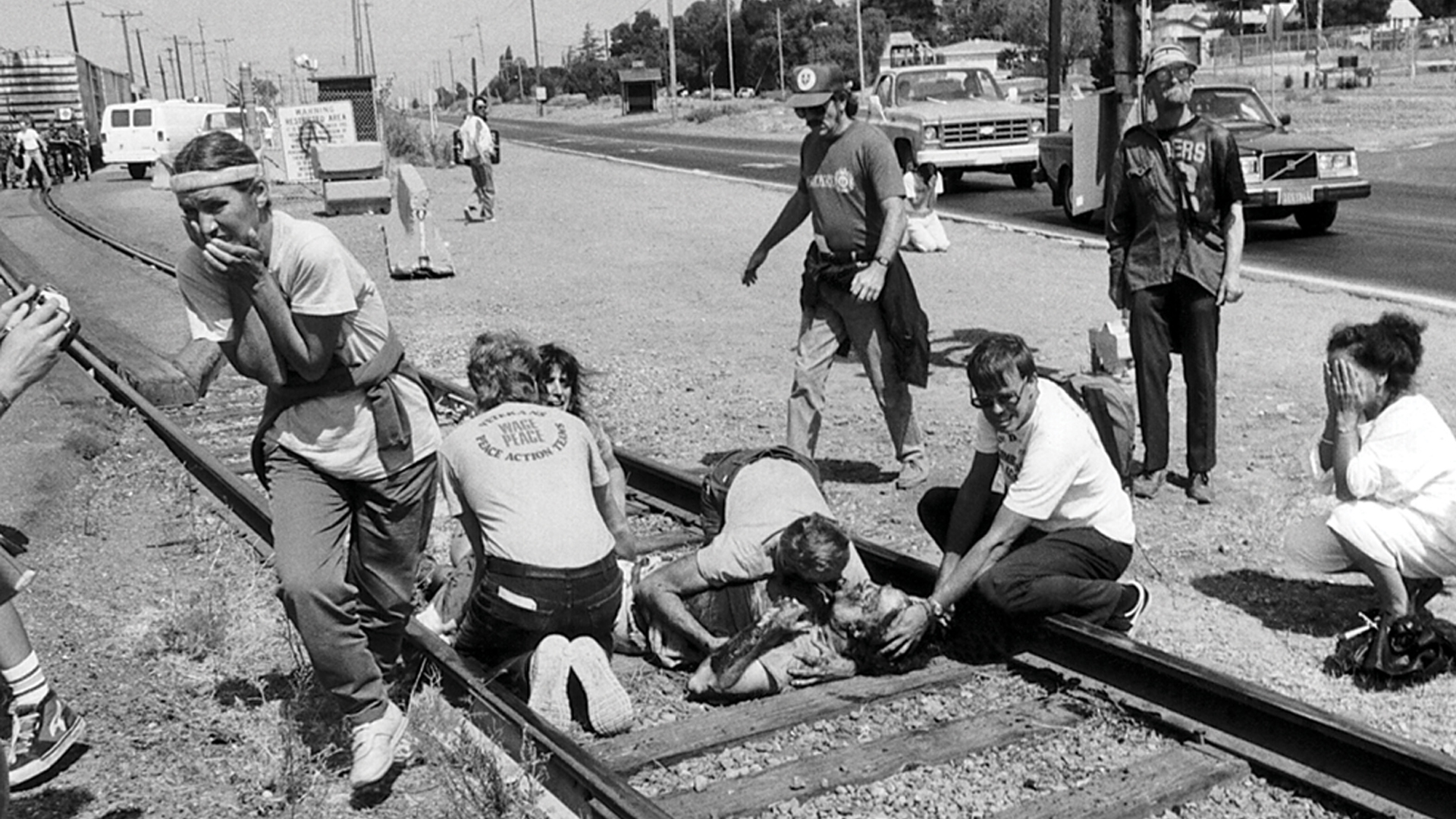

After

witnessing the effects of an American napalm raid on a peaceful

Vietnamese village, Willson, a former all-conference athlete and scion

of American conservatives, returned home to participate in antiwar

protests. By the eighties Willson was organizing military veterans to

oppose the Reagan administration’s three wars in Central America. Then,

on September 1, 1987, he and fellow veterans David Duncombe and Duncan

Murphy sat on a curving stretch of railroad track that crossed a public

road. Their goal was to block munitions shipments from the Concord Naval

Weapons Station in California to American proxy armies in Central

America. As the train approached, traveling at more than three times the

legal speed limit of five miles an hour, it became clear it wasn’t

going to stop. The protesters scrambled. Murphy, a sixty-six-year-old

World War II veteran, jumped up to grab the locomotive’s cowcatcher,

then leapt to the side. Duncombe was also able to jump clear.

Willson

was not. The train ran him over, severing one leg and mangling the

other, and carving a chunk out of his skull. (He would end up losing

both legs and his right frontal lobe.) A navy ambulance arrived quickly,

but the medics refused to work on Willson, who was bleeding profusely,

because, they said, they couldn’t treat people who were not technically

on navy property. Seventeen minutes later a county ambulance arrived and

rushed Willson to the hospital.

During a government inquiry navy

officials acknowledged that they had anticipated a “confrontation

sooner or later” with the veterans. The action had been widely

publicized, and the tracks at that location had been blocked by

protesters going back to the 1960s. So there was an established protocol

for making arrests before the trains moved. No one, particularly not

the three blockaders, expected the train to barrel through. Nonetheless

the train’s engineer told investigators that his superiors had

instructed him not to stop that day, to “prevent anyone from boarding

the locomotive” and hijacking it. Willson was never able to determine

exactly how high up the chain of command these orders originated, but

former fbi agent Jack Ryan revealed that he had been fired for refusing

to investigate veteran peace activists, including Murphy and Willson, as

“domestic terrorists.”

Immediately after the incident thousands

of people descended on Concord. Four days later, with Jesse Jackson and

Joan Baez looking on, protesters ripped up the tracks at the naval

weapons station. After the navy made repairs, a twenty-four-hour-a-day

occupation of the tracks began. It blocked every munitions train leaving

Concord for more than two years. More than two thousand people were

arrested, and some were jailed for as long as six months.

I met

Willson nearly twenty years later, when he lived near me in Arcata,

California. We would chat at the post office or see each other in the

neighborhood. He walked on prosthetics, and if anyone deserved to use a

car it was him, but Willson pedaled almost everywhere to reduce his

carbon footprint. Sometimes when we talked, he spoke of his frustration

with writing a memoir.

It wasn’t coming easy.

When the book came out in 2011, I had to wonder if Willson’s frustration had been simply self-effacement. Blood on the Tracks: The Life and Times of S. Brian Willson

is gripping and at times beautifully written. I’d place it among the

most important American histories since Howard Zinn’s A People’s History

of the United States. Willson lucidly blends the personal and the

political, and reaches well beyond U.S. activities in Southeast Asia and

Central America to connect the dots of American exceptionalism,

expansionism, and warfare around the globe since the country’s founding.

He followed the memoir up in 2012 with My Country Is the World: Photo

Journey of a Stumbling Western Satyagrahi.

Willson grew up in

upstate New York. His parents were conservative Baptists, and his father

belonged to the John Birch Society and contributed to the Ku Klux Klan.

Willson was a top student, a captain of sports teams. He went to

church, studied the Bible, and attended anticommunist Christian student

gatherings. In 1964 Willson supported Republican Barry Goldwater for

president, pleased that he was advocating bombing targets in North

Vietnam and using tactical nuclear weapons to defoliate the

demilitarized zone that separated North from South Vietnam.

Willson

was a lieutenant in the U.S. Air Force when he finished his master’s

degree in criminology at American University Washington College of Law

in Washington, DC. Less than a year later, in 1969, he shipped out to

Vietnam, where he served as a security-and-intelligence officer charged

with protecting South Vietnamese air bases. While there he inspected a

recently napalmed village “to perform a quick estimate of the pilots’

success at hitting their specified targets,” he says.

Arriving at

the village less than an hour after it had been strafed and bombed,

Willson writes that he “saw one young girl trying to get up on her feet .

. . but she quickly fell down. A few other people were moving ever so

slightly as they cried and moaned on the ground. Most of the . . .

victims I saw were women and children, the vast majority lying

motionless. Most, I am sure, were dead.” As he walked, Willson’s forward

progress was stymied by bodies. “I began sobbing and gagging. . . . I

took a few faltering steps to my left, only to find my way blocked by

the body of a young woman lying at my feet. She had been clutching three

small, partially blackened children when she apparently collapsed.”

It

was in this moment that Willson became a war resister. Back on base he

began questioning his superiors about reasons for the bombing raids,

which led to his early return to the United States and, after another

year at a base in Louisiana, an honorable discharge. He returned to

American University, received a law degree, and was admitted to the

District of Columbia Bar.

In 1973 the city of Cincinnati, Ohio,

hired Willson as a consultant on the construction of a new

criminal-justice complex. As part of his research Willson lived for

three months in the hundred-year-old Cincinnati Workhouse prison.

Afterward he proposed a new prison half the size recommended by the

state’s architect and emphasized the need for “constructive

rehabilitation programs” in lieu of incarceration — suggestions that

were ultimately ignored. In the midseventies Willson served as

coordinator for the National Moratorium on Prison Construction, a

project of the Unitarian Universalist Service Committee.

In 1980

Willson became a legislative aide to Massachusetts state senator Jack

Backman and advised the senator on prison and veterans’ issues. Willson

made regular visits to Massachusetts prisons, especially Walpole, a

notoriously violent institution where guards were known to torture

prisoners with beatings and compulsory rectal searches. At Walpole

Willson witnessed two guards “pull[ing] a prisoner out of a cell onto

the walkway floor. One guard kicked the prisoner while the other hit him

with a billy club, the prisoner screaming, the guards shouting.”

The

experience sparked a flashback to the carnage he’d witnessed in

Vietnam. It was, he says, “different from having a bad memory pop into

your mind. When I looked around me, I could only see this woman’s eyes,

dead children, the gored water buffalo lying on the ground. I smelled

the burned corpses and buildings of that village. I literally could not

see, hear, or smell the real world of the very noisy prison around me.”

The

flashback compelled Willson to take a leave of absence from his job,

which he eventually left altogether to join other vets who opposed U.S.

foreign policy. In 1982 Willson cofounded the Veterans Education

Project, and less than two years later he became executive director of a

Vietnam Veterans Outreach Center in western Massachusetts. He also

volunteered on the U.S. Senate campaign of fellow Vietnam veteran and

war protester John Kerry. After being elected, Kerry appointed Willson

to a veterans’ advisory committee. In 1986 Willson and three decorated

veterans fasted for forty-seven days on the steps of the U.S. Capitol to

draw attention to the Reagan administration’s funding and training of

the Contras, a mercenary army seeking to overthrow Nicaragua’s left-wing

Sandinista government. One year later Willson lost his legs attempting

to stop arms shipments to the Contras.

After recuperating from

the incident in Concord, Willson traveled to Nicaragua several times,

where he was greeted by cheering crowds and shared a podium with

President Daniel Ortega. He also traveled to El Salvador, Colombia, the

Palestinian territories, Ecuador, Brazil, Iraq, Cuba, and Chiapas,

Mexico. U.S. society, he felt, was in need of physical and spiritual

transformation. “Our obsessive pursuit of materialism has preempted the

evolutionary social-biological compact that guided our species for

millennia,” he writes. “I believe human beings come into the world with

the archetypal characteristics of empathy, cooperation, and mutual

respect. We are wired as social beings. Yet these fundamental

characteristics have been buried under an avalanche of narcissistic,

egocentric behavior fueled by modern materialist culture.”

During

the late nineties Willson stopped traveling the globe and began moving

across the landscape almost entirely by handcycle. He lived in small

communities, where he and his partner, Becky Luening, practiced

sustainable living by installing solar panels, growing their own food,

and buying locally. “Part of me wanted to drop out completely,” he says.

Instead he organized bike rides. In 2006 Willson and a dozen other

cyclists, many of them veterans, rode from Eugene, Oregon, to Seattle,

Washington, and back to attend the Veterans for Peace National

Convention. During the summer of 2011, at the age of seventy, Willson

handcycled from Portland, Oregon, to San Francisco, “pedaling” his book

at speaking engagements along the way. He figures that, since he first

began using a handcycle in 1997, he has logged sixty thousand miles.

On

September 1, 2012, Willson and dozens of other peace activists gathered

in Concord to commemorate the twenty-fifth anniversary of the train

assault. Several luminaries attended, including former high-ranking cia

official Ray McGovern and Pentagon Papers whistle-blower Daniel

Ellsberg. The day’s events were documented by Bo Boudart, a filmmaker

who is planning a feature film on Willson’s life titled Paying the Price for Peace: The Story of S. Brian Willson and the Peace Movement (payingthepriceforpeace.com).

I

interviewed Willson last year in the Portland home he shares with

Luening. Willson gave me a tour of their converted urban landscape. Much

of their food comes from a permaculture garden, solar panels provide

most of their electricity, rainwater irrigates the plants, and a

composting toilet eliminates the need to join a centralized sewage

system. These efforts, Willson said ruefully, amount to little more than

gestures verging on “greenwashing.” Yet Willson and Luening continue to

work closely with like-minded neighbors to eschew centralized,

fossil-fuel-dependent systems as a path toward even higher levels of

community sustainability and, by extension, peace.

King: In

Vietnam you accompanied a South Vietnamese lieutenant into a village

that had been napalmed just an hour before. Burned and blown-up bodies

of women and children lay scattered about. But when you broke down, the

lieutenant couldn’t figure out what your problem was. How was his

reaction humanly possible?

Willson: I think we’re all capable of being in denial of our humanity. And we’re all capable of participating in evil.

When

I looked into the eyes of a dead woman I saw there, what I experienced

wasn’t a thought; it was an overwhelming sensation that hit my body. The

lieutenant asked me what was wrong, and my brain and nervous system

struggled to come up with words. “She’s my sister,” I finally said. It

was just an interpretation of what I felt. It’s like when a father goes

home and sees his child and just wants to hug her. It’s a response that

comes out of your whole being. It’s love. It has nothing to do with

thought.

King: But how was the lieutenant able to shrug at such a massacre in his own country?

Willson: Many

of us are conditioned to be obedient to some master or ideology. The

ideology usually includes a class structure in which some members of

society are more privileged. You constantly have to demonize other

people in order to justify such privilege. I had that conditioning. The

lieutenant had it too. He was from an upper-class Vietnamese family that

had collaborated with the French for many generations, and he’d been

sent to a French school and also educated in the United States.

I

was kind of a lower-middle-class kid who was trying to become rich and

successful. The experience I had in Vietnam caught me by surprise.

Before that, I’d been a creature of compliance, concerned with making

money, saying the right things, dressing the right way.

The

question is: What causes the break from that conditioning and the

recovery of one’s empathy and sense of cooperation? I don’t really know.

I recently read The Lucifer Effect, by Philip Zimbardo, who conducted

the Stanford prison experiment. [In 1971 Stanford student volunteers

were randomly divided into “guards” and “inmates” and placed in a mock

prison environment. Within a week the study was shut down because the

“guards” had become brutal and sadistic. — Ed.] In the book Zimbardo is

trying to figure out how good people can do evil things — and how some

can then revert to being humane and caring.

I hesitate to say

that my transformation after visiting the bombed village was automatic. I

knew that I was the bad guy, but I also wondered: How could that be?

How could I be a bad guy? I hadn’t pulled the trigger. I hadn’t dropped

the bombs. But I was complicit in this whole system. By protecting the

air base from attack, I’d enabled the planes to conduct their bombing

missions. Maybe it was my removal from the actual act of killing that

enabled me to see it as the horror it was.

Before Vietnam I’d thought that being born in the U.S. was enough to make me a “good guy.”

But

seeing that woman’s eyes, it was so clear. It was such an overwhelming

truth. It was irreversible. The only options were just to get drunk or

high and stay that way my whole life, or to embrace the truth.

Sometimes

I wonder: Why was I asked to do that extra duty? It was very unusual

that I was even in that village, assessing bombings. I didn’t know any

other air-force officer who was doing that. It was just a fluke. I like

to think of it as divine intervention. It was the Great Spirit talking

to me, telling me I was not going to slide through this world. I wanted

to slide through it. I wanted to go to graduate school, not study too

hard, get my degree, get a nice job, and make a lot of money. But that’s

not real, the Great Spirit said. I was going to have to deal with the

hard truths.

I can still hear the moaning from the villagers who

hadn’t died yet. I left that village while people were moaning. I didn’t

even summon any medical help.

Their moaning is now my moaning. I

am connected to them, not separate. We’re all connected by empathy. I

believe there is a soul in everything. God is in everything, and it’s

all connected.

If you can really feel that type of connection,

then your life will be radically changed. You will make completely

different choices. And it’s not enough to know you’re connected. You

need to feel the connection. Feeling is a wisdom that we’ve lost. During

the Enlightenment, in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries,

rationality was emphasized over feelings, with damaging effects. The

Enlightenment thinkers made interesting contributions to reductionist

principles, but not to holistic principles.

King: Your memoir came out around the time of your seventieth birthday. Can you give us a synopsis of your story?

Willson: I

think of myself as a recovering white male, recovering from my early

conditioning about how to be successful. The value system I was raised

with dehumanized me to the point that I followed an order to travel nine

thousand miles to participate in destroying another people. It’s

incredible that I could do that, and without really thinking much about

it. That’s why I wrote the book — to understand how it was so easy for

me to do that. I’m still recovering from it. It’s a lifetime journey,

and there’s no happy ending. But it is a story that contains a certain

amount of joy: the joy of learning the truth.

King: You have called the incident in which you lost your legs “attempted murder.” Why?

Willson: The

navy’s protocol was for the train to stop and wait for arrests.

Remember, I was once a military-installation security commander. I know

how to secure equipment. Because they were carrying munitions, they were

required to stop. Suppose I’d had a satchel of charges strapped to my

body: I could have blown up the whole train, and a lot of people would

have been killed. So not stopping was against protocol. And it was also

intentional. Subsequent testimony revealed that the engineer had been

ordered not to stop, and the train had sped up to three times the legal

five-mile-an-hour limit.

King: You have said you were surprised the engineer didn’t stop, but you were not surprised that the government assaulted you.

Willson:

In Concord I experienced what people all over the world experience when

they stand up to power: they get clobbered. Look at the history of the

U.S. labor movement. About seven hundred labor organizers and strikers

were killed between 1880 and 1930. Our history is violent. But the

official history says that we are the greatest country in the history of

the world, because we defeated fascism in World War ii.

King: Did you go through a period of mourning for your lost legs?

Willson:

I did, but it wasn’t until years later — about 1993. I started crying a

lot. I didn’t want to go anywhere, because I didn’t know when I was

going to break down. In my mind nothing was prompting this. It was

spontaneous. I was crying that I didn’t have my feet, but at the same

time I was thanking my legs for adapting to these prosthetics and

getting me around. I would caress my stumps, sometimes for hours a day,

just appreciating what I had. They do such a phenomenal job, because I’m

active, and I don’t give them much of a break.

King: When did you start riding a handcycle?

Willson: In

1997. Until then I hadn’t even known they existed. I discovered them in

Northampton, Massachusetts. The state had an office that was loaning

out handcycles. They weren’t like the one I have now — they were more

like wheelchairs — but I was hooked right away. I used that borrowed

handcycle every day for probably a month. Then I bought one, and I’ve

been riding ever since.

I often wish that back in 1900 people had

been able to think more clearly about the implications of burning

fossil fuels. The internal-combustion engine arrived on the scene about

the same time that bicycles had come into their own, with pneumatic

tires and ball bearings. We went for speed, comfort, and convenience.

These are not holistic principles. And we had a technology that would

have enabled us to live simpler, more efficiently, and healthier.

Economist

E.F. Schumacher said that “small is beautiful.” According to his fellow

economist Leopold Kohr and social critic Ivan Illich, the most

efficient speed for human society is that of a bicycle: twelve to

fifteen miles an hour. So slow is beautiful, too. And so are less and

local.

Those may seem like just words, but really they are guidelines for an alternate vision.

King: You and your partner, Becky, have tried to live that vision. Are you satisfied with the results?

Willson: We’ve

been trying to downsize because, for humanity to survive, we all need

to radically simplify our lives. Becky and I have insulated our house.

We’ve got double- and triple-paned windows. We’ve got solar panels. We

heat with wood, and it’s all local wood. We have an efficient stove. We

eat dinner by oil lamp year-round. And we keep track of our

kilowatt-hours, trying constantly to reduce our energy use. We actually

have charts. We terminated all gas coming in the house. We use

solar-tube skylights. We grow food. We collect rainwater. We recycle. We

compost our sewage.

King: Those sound like significant achievements.

Willson: Yes,

but now I think we have to figure out a way to live without grid

electricity, which means another radical downsizing. I meet regularly

with a small group to discuss these subjects. We encourage one another

to stretch our boundaries and push against perceived limitations. We ask

questions such as “What is the embedded energy in a solar panel?”

King: What is “embedded energy”?

Willson: It’s

all the energy it took to produce that product. For instance, this

chair. A lot of energy was used to bring this chair into being and get

it to this room. Materials had to be mined, and for that, extraction

equipment had to be built, and a factory had to be constructed to make

the extraction equipment. You had to get the extraction equipment to the

mining site, and you had to extract the raw materials out of the earth

and load them into a truck that was manufactured in another facility.

Each of these manufacturing facilities requires thousands of parts.

Fossil fuels are utilized at every stage of the process. Then you have

to move the finished product to distribution centers, and from the

distribution centers to the point of use.

You have to build more

roads and more trucks and fuel them. And that’s just a chair. A solar

panel requires even more energy and materials.

King: These things also usually require a fair amount of fresh water.

Willson: Absolutely,

which results in pollution. In all of these processes you’re putting

carbon molecules in the air. Just to make a computer chip for a

smartphone they have to cook it to 4,500 degrees to embed the memory. It

takes a lot of energy to get that much heat, and huge amounts of water.

But we are addicted to our technology and our way of life.

King: People

in Portland seem to be ahead of the curve in terms of steering

neighborhoods away from dependence on fossil fuels, but you have said

that’s not enough. How so?

Willson: We had 220

people at our place one Saturday during a Portland “green tour.” It was

fun, but deep down I was thinking, This still isn’t the truth. I’ve done

what the capitalists want.

For example, I’ve created three solar

houses: I built a straw-bale solar house in Massachusetts, I

retrofitted a house in Arcata, California, and I retrofitted this house.

And I’ve done it all the way the green experts say I should. But I

bought all I needed for the projects from the capitalist system.

Whatever

the next groovy idea is, the capitalists are going to figure out how to

make money on it. I enjoy generating electricity from the sun, but in

the big picture I want to be part of a community that isn’t dependent

upon electricity at all.

King: Has anyone in your group actually moved beyond using new “green” technologies?

Willson:

Not yet. There was a couple who lived without electricity for a year.

They just shut it off. But they found that it was very difficult without

help from a larger community.

Real community can replace our

dependence on unsustainable systems. The community is the system. I want

to facilitate local relationships, local commerce, local interactions. I

want to help people understand that we’ve all been sold a bill of

goods, and now our task is to recover our humanity. And we do that by

asking questions and experimenting. Can we live a whole year without

buying food that comes from more than a hundred miles away? There are

some people doing that. But now we’re talking about a “hundred-foot

diet.” A permaculture advocate in this neighborhood says she’s going to

grow all her food on her five-thousand-square-foot lot.

The fact

that there are people thinking like this is exciting. I mean, what

Becky and I have here is ok , but it’s pretty bourgeois for a couple of

activists. If I had my dream, I would be living in a group of about

fifty people and using draft horses and growing all our food. I want to

live in a community where neighbors are constantly interacting around

food.

King: Is it possible for everybody in a

city the size of Portland to scale that far back? Can everybody do what

you’ve done? It’s hard enough getting the kids to school and getting to

work on time, much less growing a permaculture garden and living without

electricity.

Willson: Well, I think anybody can

do what we’ve done, but you have to want to do it, and it does take

some money. If our nation weren’t spending $14 billion a month on wars,

we could be redistributing wealth, but that’s not going to happen,

because we have a plutocracy. No savior from outside is going to help

us, including the federal government — especially the federal

government.

People ask, “How can we create more jobs?” I don’t

want to create more jobs. Having a job is not natural or healthy. Humans

are meant to have work, to be fully engaged with the life of food —

planting, harvesting, celebrating, and eating it. But to have a job

where you work for somebody else? That’s a relatively new phenomenon in

human evolution, only about five thousand years old. You work for the

king or one of the king’s managers. That’s not normal.

That’s not healthy.

You

can grow your own food. You can also learn about the forest, about

mushrooms, about natural food sources. You can learn that you’re part of

nature. In Portland a lot of people are growing food who weren’t

before. They are growing food in the strips of grass beside the curb.

This is a radical step. People are beginning to understand the limits of

our industrial, centralized systems. Even if we can’t grow all our own

food, we can eat food that’s been grown locally.

The earth is finite. There’s not enough carrying capacity on the planet to feed 7 billion people.

Yet

we continue to live as if there were no limits. We have separated

ourselves from nature. We think we are superior to nature, and we

believe our technology will always come up with a solution for shortages

or pollution or whatever problems we’re facing. It’s a Faustian

bargain. Most scientists agree that ecological changes and global

climate instability are making it difficult for people to survive, and

it’s only going to get worse, especially for those who live along the

coastlines.

Our economic system requires endless removal of

resources all over the planet. We continue exploiting the earth even

when the exploitation itself threatens our survival. We are running out

of clean water. We are running out of easily accessible, cheap oil,

which has been the basis for the last century’s worth of industrial

development. When oil supplies start getting short — say, 3 percent or 4

percent below demand — it will cause a panic, because trucks won’t be

able to get to every store with the food people are dependent upon, food

grown 1,500 miles away.

Look at the resources being used every

day to maintain this modern life, and then look at how much pain and

suffering is necessary to enable this life.

King:

What about modern devices such as cellphones and the Internet? Are

there no redeeming values to them? I have enjoyed your blog and Facebook

postings many times.

Willson: The rare metals

used in computers and cellphones have not just an ecological price but a

human price as well. I have a friend, Keith Snow, who’s been a

journalist in the Congo off and on for the last fifteen years. He has

seen the plunder of resources for high-tech devices: metals such as

cobalt, coltan, niobium, and germanium. Keith says 10 to 12 million

Congolese have died since 1995 in wars fomented by corporations and

Western governments who want access to these metals.

I don’t own a cellphone. I might die on my cycle someday because I have an accident and don’t have a cellphone, but that’s ok.

That

said, I’m not going to tell people what to do. I’m just going to say

that the human and environmental consequences of the electronic-gadget

revolution are devastating. And, yes, I do have a laptop.

King: Jet fuel is a major contributor to global warming. Do you fly in planes?

Willson: I

stopped flying eleven years ago, but I can’t tell people not to fly. I

flew half a million miles before I was sixty, and I gained a tremendous

amount of cultural experience because of it. Refusing to fly in

airplanes now is a move toward mutual aid and respect, but it’s a mere

gesture. I live in incredible comfort when so many are suffering. I

continue to make choices each day that remain at odds with mutual aid

and respect.