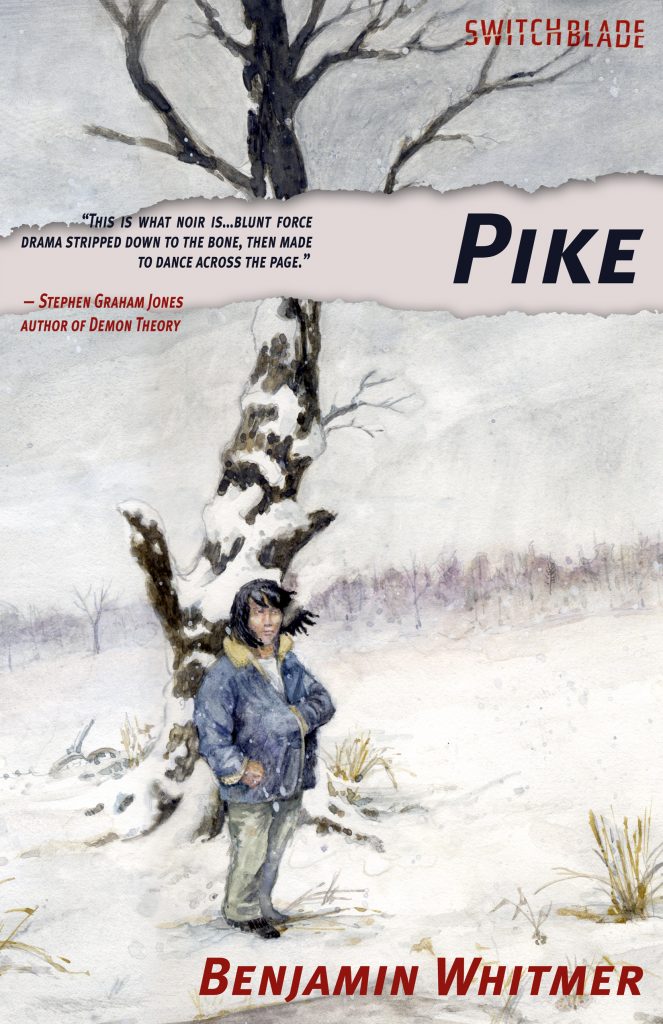

Since the death of Larry Brown there have been at least a dozen novelists touted as the heir to Brown’s gritty throne. Needless to say, there have been few who’ve actually lived up to the promise. However, with Benjamin Whitmer’s stark debut, Pike, the Denver, Colorado based novelist easily rivals Brown’s most renowned novels. Recently I was lucky enough to contact the author to discus Pike and other upcoming writing projects.

Keith Rawson: For those who aren’t familiar with Pike, what’s the novel about?

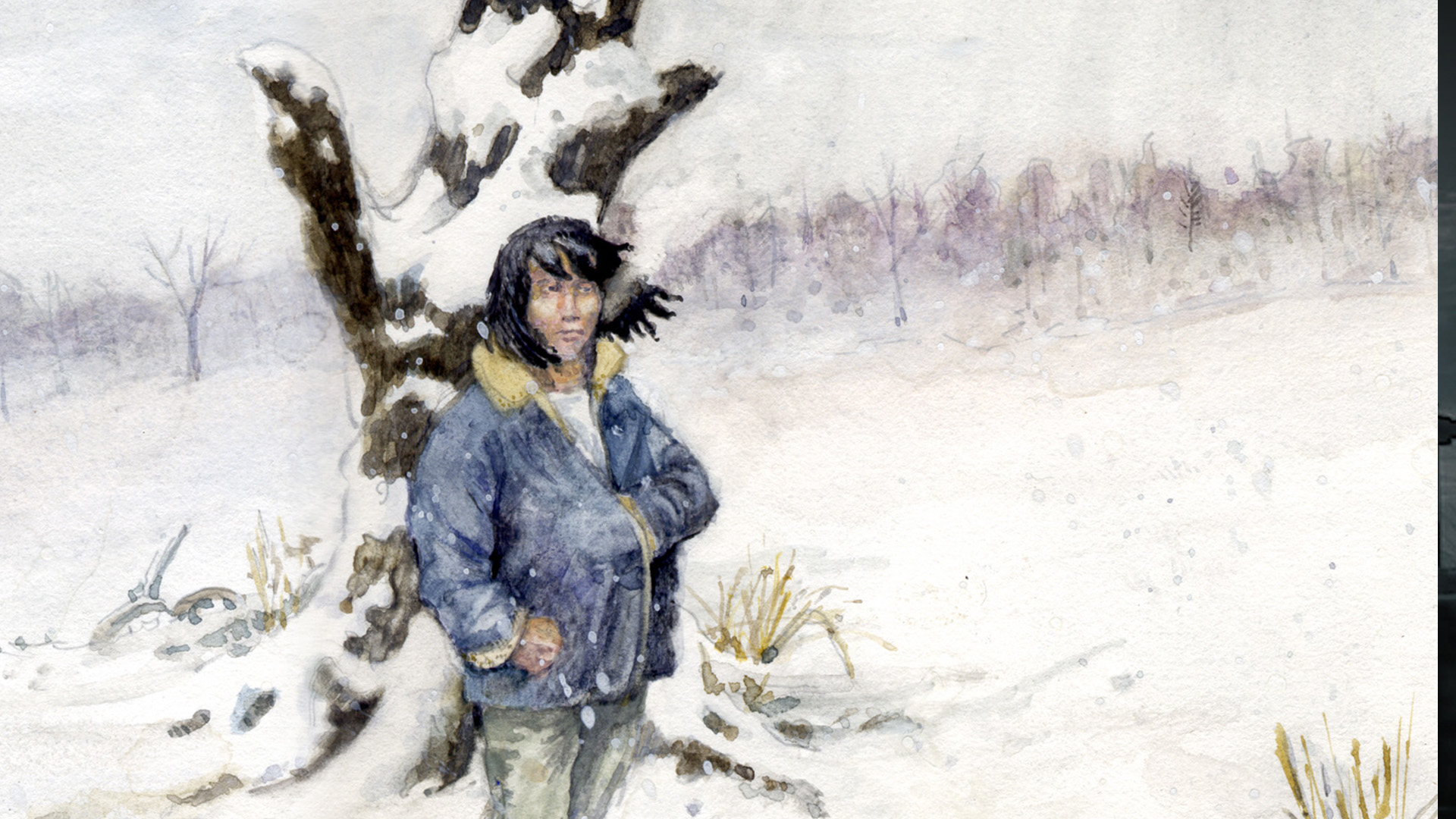

Benjamin Whitmer: I have some kind of moron mental block when it comes to describing the book. The best I can usually come up with is to tell people it’s about four characters. The first, Pike, is a reformed drug-dealer, murderer and mule who lives in a small town in Eastern Kentucky; the second, Derrick, is a Vietnam-haunted corrupt Cincinnati cop driven half insane by his own pacemaker; the third, Rory, is an aspiring boxer carrying more than his share of family horror; and the fourth, Wendy, is the teenage girl who all three men are trying to use to redeem their pasts.

Where did the idea for Pike first get started? How did this character first come to you?

It got started with the characters of Pike and Wendy. I was living in Cincinnati at the time and spending a lot of time in Kentucky and rural southern Ohio, and I started to get this image flickering through my head of this life-battered runaway girl walking side-by-side with some big hulking bruiser. That image grew and grew — I remember feeling like I was watching the two of them fill out physically — until one day I just started writing.

You paint Cincinnati as a sharply divided, racially charged city. How much of this is fiction and how much is fact based?

I don’t think any of its fiction. Race and class cut across Cincinnati more clearly than anywhere I’ve ever been, and it’s all tied geographically. If you tell people you live in, say, West End, let alone Over-the-Rhine, you’re gonna get a completely different reaction than if you tell ‘em you live in Hyde Park or Mt. Lookout. Race and class were always in the air when I lived there. The white talk radio shock jocks didn’t even try to hid their flatout racist horseshit, the mainstream newspaper in town wasn’t much better, and, of course, the police were completely out of control. I remember six cops beating an unarmed black guy to death for being a tipsy and doing a little dance outside of a White Castle, and the reaction from the local media, not to mention around the water cooler — at least where I worked — was, “yep, he deserved it.”

Which is not to say, of course, that race and class concerns are any less omnipresent anywhere else. The divisions are just as complete where I live now, in Denver, but they’re swept under the rug to a far greater degree.

That actually segways well into my next question: What kind of cultural differences are there between Cincinnati and Denver? Do you see the same kind of have and have not divide in Denver as you saw in Cincinnati? Also, how did you end up in Denver?

I actually lived in Denver before moving to Cincinnati. My wife and I have lived out here off and on for more than a decade. We moved back there figuring the cost of living would be cheaper. It was, but at the cost of being able to find work. There’s ups and downs to both. I miss all the green of southern Ohio and Kentucky, but, then, I’ve got a big thing for the American West. Always have. And though you do see the same class divide in Denver as you do in Cincinnati, it’s not quite as overwhelming. Decent jobs with health benefits and all the stuff you need to support a family, they’re damn near impossible to come by in Cincinnati. They’re not easy to find in Denver, but it is possible with a little luck. Cincinnati’s the rust belt, and all those jobs, they’re long gone. Denver has more of a technology-driven economy of the sort that has yet to be entirely exported out of the country — though it’s disappearing fast.

Was Pike your first attempt at writing a novel and is there any of your other work floating around out in the world?

I actually wrote a practice novel before Pike, but I wake up every night in a cold sweat fighting off nightmares of somebody finding a copy. And I know there are some short stories and such out there floating around, but trust me, they’re unreadable. It took me a very long time and probably thousands of shredded manuscript pages to get through what I consider my apprentice phase. Other, more talented, people do great work when they’re young, and I’ve got nothing but admiration for them, but it took me a long time to just get the basics down, and I feel like I’m only beginning to get a bead on what writing is all about. I figure by the time I’m fifty I might write a sentence I like.

How long did it take you to finish writing Pike?

It took me about two and a half years of plugging away. It seems like it took even longer when I think back on it. I write really, really slowly, and I throw a lot away.

Why did you decide to set the novel in 1985 as opposed to writing it in a modern setting?

There were a couple of reasons, but the major one was just a matter of timing. I wanted Derrick to be a Vietnam veteran, but I also wanted him younger than Pike, and that meant I had to set it in the 1980s. I was a kid in the 1980s, but I remember Vietnam being everywhere. Every haunted cop, every suicide, every alcoholic, every fucked up family had Vietnam as the subtext, and from the minute I started thinking about this book I knew it had to have one Vietnam-ruined cop — a kind of anti-Magnum PI. I went through a lot of revisions before I landed on Derrick, but the minute I started to get him in my head, I knew he was perfect.

Do you consider yourself a crime/noir novelist or does designation/genre mean anything to you as a novelist?

I don’t know what I consider myself. I’ll admit I didn’t sit down to write a crime or a noir novel, but when my agent said that’s what it was I was happy about it. I know what makes a police procedural or a spy thriller, but to be honest, I don’t even know what makes crime fiction. I mean, does Faulkner’s Sanctuary count? How’s about Harry Crews’ A Feast of Snakes? Likewise, though Ellroy’s work definitely falls in the crime/noir genre, I read a review recently that compared his latest book to Roberto Bolaño’s 2666 that I thought was really smart.

For me, I write novels about damaged, complicated, often-violent people, because those are the kind of people that interest me. If that’s considered crime fiction, I’m honored to be part of that community. It’s includes some of the best writers in the world, genre be damned.

Pike isn’t your typical noir tough man, were there any genre templates you utilized when creating him?

I don’t know if there was a template, but I was definitely reading a lot of James Ellroy and Jim Thompson, and thinking about the way they just drop you into these massively flawed characters and don’t really ask for your approval or forgiveness. I’m not a real violent guy, not by a long shot, but I’ve known some who are, and they’re not sweethearts %99 of the time and only tough guys that other %1. The ones I’ve known are fucked up by what they are. They eat their own shit every day of their life trying to live normal lives. I kept that in mind when I was thinking of Pike’s character.

Some of the imagery in Pike really shook me, particularly Rory’s flashback of his little sister in chapter 31. Were there moments in the novel when you had to step back after writing a scene like that? Are there moments as a writer where you self censor and choose to hold back?

Yeah, sometimes I do have to step back for a minute. I tend to pace a lot, and some of those scenes set me pacing more than others. I believe I took a late-night walk around the block after the scene you’re referring to. The thing is I really do love my characters — even the ones who aren’t so lovable, like Derrick — and I get attached to them. That said, I don’t think I ever self censor in that way, not because something’s too sad or too terrible. Or, at least, I try real hard not to.

Y’know, Flannery O’Connor had a great line about her writing: “When you can assume that your audience holds the same beliefs as you do, you can relax a little and use more normal means of talking to it; when you have to assume that it does not, then you have to make your vision apparent by shock—to the hard of hearing you shout, and for the almost-blind, you draw large and startling figures.”

I’m not comparing myself to O’Connor, not by any stretch of the imagination, but that line is one of those things that I always keep in the back of my head when I’m writing. And with that drawing of “large and startling figures” comes the danger of exaggerating to the point of absurdity. I try to be always vigilant against that, against crossing that line from pathos to parody. So I do self censor in that way.

Are you currently writing a follow up novel?

It took a long time to get Pike published, so I’m actually almost done with one, half done with another, and I’ve got what I think is a damn good idea for a third. I’ve had a pretty big non-fiction opportunity drop in my lap recently, though, so I’ll probably put those on hold for the next six months to a year and concentrate on that.

With your non-fiction project, is it something that you can talk about at this point?

I don’t want to say too much about the non-fiction project because the contracts haven’t been drawn up, and I’m superstitious. Generally, it’s co-writing an autobiography for a country music legend with one hell of a life’s story — somebody who’s finger prints are all over pretty much all the music I love. (Do I sound excited?) One of the coolest things is that if it all pans out it’ll be excerpts from Pike that landed me the gig.