By Ellen Barfield

WIN Magazine

Spring 2012

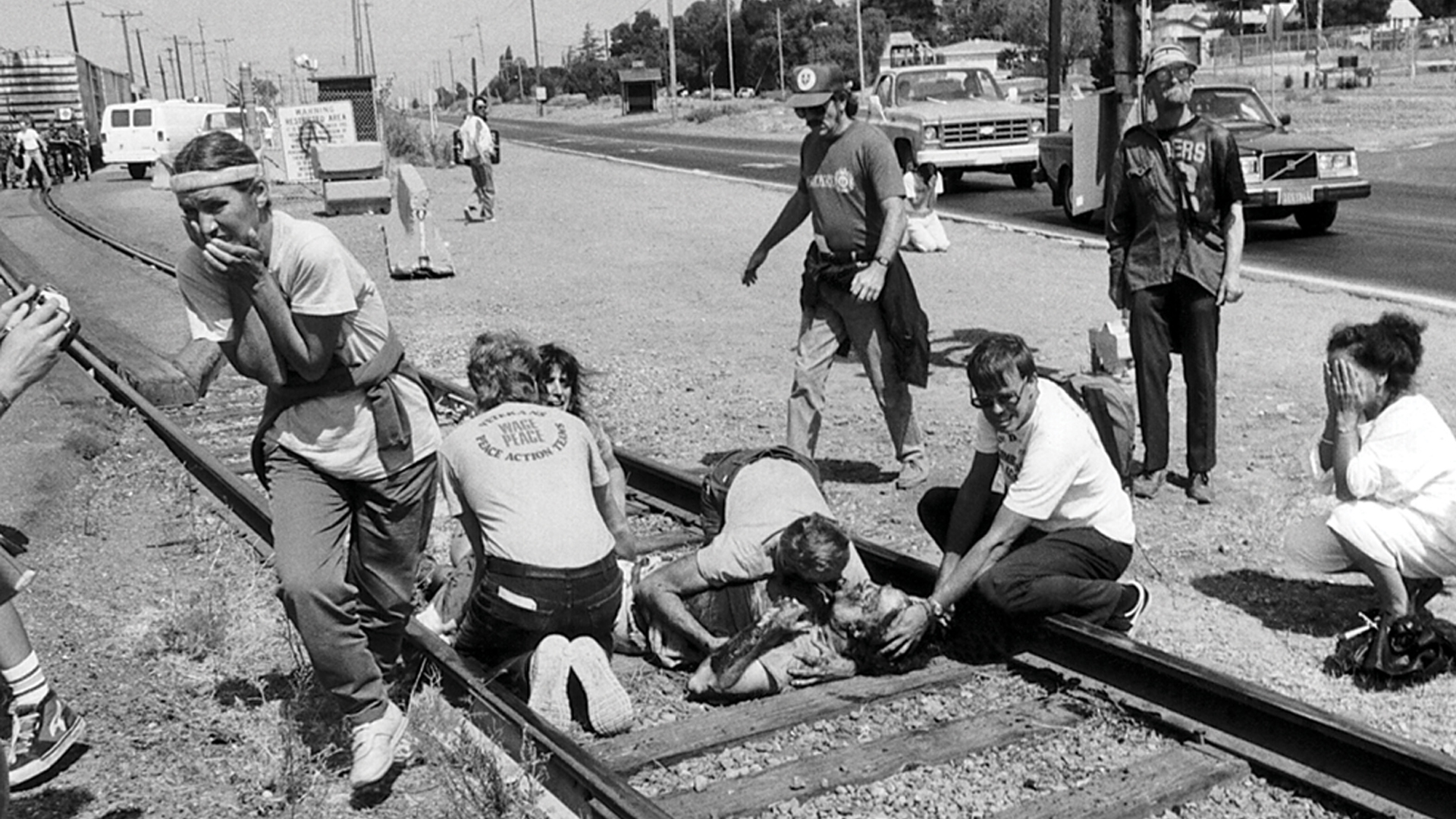

Rejecting “AWOL”

On the evening of September 1, 1987, I walked into the living room of the home I shared with my then-husband, glanced at the television, and was horrified to see news footage of peace activist Brian Willson being run over by a weapons train at Concord Naval Weapons Station in California. I have never forgotten the lesson I learned that night, early in my activist career: that our government will go as far as to kill peace activists if it feels it necessary. Brian’s survival was due to the exact nature of his injuries and the presence of his then-partner Holley Rauen, a nurse-midwife who stopped him bleeding to death from his severed legs. The military ambulance on the scene refused to help Brian because he was just inches off government property when his battered body finally came to rest.

Brian’s memoir, after long years of understandable writer’s block, is a poignant examination of his journey from obedient and oblivious conservative lower-middle-class white kid in the complacent United States of the post-World War II years to fiery outspoken critic of U.S. imperialism and materialism. He was drafted into the military out of law school because his student deferment was not absolute. He was from an upstate New York farming county where many young men received necessary farming deferments. In his combat training, he physically could not bayonet a dummy, foreshadowing his later radicalization. In Viet Nam he worked as a security officer at an air base in the Mekong Delta. While doing body counts in a hamlet, he gazed into the eyes of a dead woman who would haunt him years later, though he suppressed the memory for a long time.

Brian came home and tried to forget his military experiences, not feeling like a veteran because he had been an officer and not seen combat. He finished law school and hired on with a prison moratorium project just as the deeply racist drug war spurred the prison boom that was to lock up incredible numbers, eventually a much higher population percentage than any other nation, of mostly African American, mostly nonviolent smalltime users. A later job as a Massachusetts legislative assistant on prison issues led him to Walpole State Prison to document prisoner torture by guards. While on a cellblock there, he had a flashback to the dead woman and a painful realization of how wrong and horrible the war was. In this traumatized state, he managed to negotiate all the gates and guards and get out of there without precipitating a violent incident, then cried in his car for hours.

After this revelation, Brian became a tax refuser, left the legislative job, and moved further from the mainstream. Realizing finally that he needed to connect with veterans, he helped set up and run a storefront veterans’ center. He was drawn into electoral work for John Kerry’s Senate race but felt betrayed when Kerry revealed he had not thrown away his own medals at a 1971 antiwar demonstration. The Nicaraguan Contra war was heating up, and Brian’s distress over what he saw in many ways as another Viet Nam led him to speak out and offend some more conservative veterans at the vet’s center. He resigned from the center and traveled to Nicaragua two months later.

The simple Nicaraguan campesino life resonated with Brian, leading him to better understand and reject the materialistic “American Way of Life,” or AWOL, the military slang for “absent without leave.” He saw this way of life maintained by imperialism, which steals material wealth from poor people around the world and kills them when they object. He fasted to protest the Contra war on the steps of the U.S. Capitol with other veterans and blockaded trains carrying weapons.

Bizarrely, the train crew brought suit against Brian for the mental anguish they experienced obeying orders to run him over. During the long legal process, it became clear that U.S. government impunity would keep the crew and those who gave the orders from being penalized, but Brian got a monetary settlement that funded years of travel all over the world to places where U.S. oppression was evident. Growing guilt at resource use for all that travel has Brian now living in a near-self-sufficient urban homestead and traveling only by hand-cranked bicycle (or by train when necessary, like on his recent book tour, but never airplane).

Brian’s tale of progressively relinquishing the myths and comforts of the materialistic U.S. lifestyle reveals admirable vulnerability to the despair of realizing our nation’s criminality. He examines the psychological underpinnings that lead humans to perpetrate atrocity under orders and includes well documented historical and personal evidence of U.S. imperialism. His philosophy is one of total solidarity with the world’s poor. As he says, “We are not worth more; they are not worth less.”

Ellen Barfield is a WRL National Committee member and U.S. Army veteran who, like Brian Willson, is a member of Veterans For Peace. She had the privilege of traveling to Palestine and Iraq with Brian in 1991.

Ellen Barfield

Baltimore-based Ellen Barfield is a member of the War Resisters League National Committee and Administrative Coordinating Committee. She has been an activist for nearly 30 years, since finishing college with Army money. She works primarily with WRL and Veterans For Peace, and has over 100 arrests on her record.