By Gregory Zobel

Freedom News

March 2nd, 2017

Gabriel Kuhn has been writing political books from the late ’90s on topics ranging from women pirates to football and the State. In this interview Freedom reviewer Luther Blisset talks to him about the Autonomen, workers’ councils and the history of anti-fascism in sport.

LB: You graduated with a PhD at a young age, at least for the US. Did you know that you wanted to do philosophy for a long time? How did you get interested in philosophy and radical politics? And why go for a PhD instead of just an undergraduate degree?

GK: I knew that I wanted to study philosophy already in high school. It was simply a fascination with questions that seemed central to our existence: is there a God or not? What is good and what is evil? What is the meaning of life? Why does something exist and not nothing?

The interest in politics developed a little later, but it quickly became very strong and, inevitably, influenced my take on philosophy. Political philosophy and ethics became the fields I was mostly interested in. During the early 1990s, when I did my studies, there was a bit of an upheaval in the humanities, at least in Europe. For many, the fall of the Soviet Union had discredited Marxism, which was still the leading ideology among left-wing academics. Interest in poststructuralist leftists — such as Michel Foucault, Jean-François Lyotard, Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari — soared. I remember the period as exciting, even though much of poststructuralist-inspired work today has degenerated into nonsensical gibberish.

The reason I did a PhD was because it was an easy thing to do in Austria. It didn’t cost you anything (university education was free and still is for the most part) and I hardly had to do any courses. All I needed to do — so to speak — was to write a thesis, which wasn’t a big sacrifice since I always enjoyed writing. That’s why I saw the project through, although I had no interest in an academic career. I’ve never had a job in academia.

LB: I remember reading that you were involved with the Autonomen for several years. How would you describe your activities? Demos? Publishing? Outreach? Could you share several of the lessons you learned from the experience?

GK: The autonomous milieu was pretty much where all radical leftists in the German-speaking world found themselves in if they didn’t want to be involved in party politics. It was very diverse and ideologically quite open. For some years, I was part of a collective in a smaller Austrian town that contributed to and distributed the country’s biggest autonomous newspaper; I guess in more modern language you’d call it an affinity group. We also went to demonstrations together and were involved in different protests — against the first Gulf War, the rise of the FPÖ (a right-wing party, today one of the country’s biggest), real estate speculation, Austria joining the European Union (at the time, opposition to the EU was a mainly leftist issue — today, it has been taken over by the nationalists). We also were involved in starting a pirate radio station, which opened the path for legal non-commercial radio projects that still exist. In 1994, I left Austria and I can’t really claim that I have been active in the German-speaking autonomous movement since, although I’ve always been following the developments and discussions and it’s still the milieu I move in when I go visit. A few years ago, I was involved in a German publishing project that tried to reevaluate the autonomous movement in the new century.

What did I learn from those experiences? Interesting question, I have never given that much thought. Obviously, it introduced me to autonomous organising, for better or worse. I learned about militant protest and direct action, security and legal issues, the publishing and distributing of literature, the dynamics of radical collectives, and about building broader alliances or at least trying to. Plus, there were many debates about goals, strategies, and tactics. I think I mainly gathered impressions for a few years and had in no way reached any particular conclusion when I left the country to travel and then live abroad. I guess what I took me with me was the feeling that you can have an impact even as a small group, as long as you’re connected to a broader movement through regular discussion and common action. If that connection is lost, however — as I feel is increasingly the case for radical collectives, at least in Western and Northern Europe — it’s easy to fit the image of an isolated social club with radical pretensions.

LB: Given your background, reading, and networks, have you seen any phenomenon or organising in the US that resembles any of the iterations of the European Autonomen? If so, could you elaborate or discuss a bit?

GK: I think that the anarchist subculture I experienced studying and travelling in the U.S. between 1994 and 2005 in many ways resembled that of the Autonomen. This concerned everything from what people wore to what they ate to the music they listened to and to the way their homes and social centres looked. All of that was very familiar. And despite certain differences in focus, the main political topics were also the same: gender, racism, anti-capitalism, and so on. Add to that the shared enthusiasm for direct action, Black Blocs, and related forms of protest and you have very similar scenes.

The strongest differences probably concerned ideology. The Autonomen were still fairly influenced by Marxism — even if it was a Marxism of the “left communist” or “operaist” variety — and I didn’t see much of that in the U.S. I hate to employ overused stereotypes, but I felt there were fairly strong anti-intellectual strains in the radical circles I encountered there. All of this might have changed, however. I haven’t been able to travel to the country since 2005 due to immigration issues.

LB: You edited a book of key source documents on Workers Councils. How did you first run into the material? And how did you decide which documents to translate into English — that must have been incredibly hard! I’m very curious about what relevance you see in getting these documents published. What have you specifically learned from working with this body of documents?

GK: The book came about in roundabout ways. Originally, I was interested in the role of the anarchists Gustav Landauer and Erich Mühsam in the Bavarian Council Republic, which existed for a couple of months in the spring of 1919. Mühsam had written a personal account of the period, and an American friend, who wanted to publish it as a pamphlet, had asked me to translate it. The pamphlet never appeared, but talking about the project with other English-speaking friends, it seemed there was a more general interest in the German Revolution of 1918–1919, especially in the radical, that is, the anarchist, syndicalist, and communist currents. The folks at PM Press were among those I talked to, and this is how the book was conceived.

The material wasn’t difficult to find. The period is well covered in German literature. I chose the texts for the English edition according to their overall importance and to how representative they were for the currents I wanted to focus on. Of course I wanted to include the most influential texts, but I also wanted to tell a story. Anthologies — in particular academic ones — all too often consist of individual texts that might be of great quality but are only loosely connected; it can be hard to identify a thread that runs through them all. For me, it seemed important to tie the individual parts together and create a narrative. So that’s what I tried to do.

As far as the relevance of publishing historical material is concerned, there is a standard answer: we need to learn from history to make the future better. More specifically in this case, the question of revolution remains unresolved. Fortunately enough, there are still a lot of people who want a socialist society; but few of us know how to even begin the discussion about how to get there. Looking at earlier attempts seems like a good starting point.

LB: How many languages are you able to translate with/across?

GK: Basically, I translate between German, English, and Swedish, although the translations into Swedish require more time and editorial help. I can also translate from French (albeit slowly) and — by default, as they are so close to Swedish — from Danish and Norwegian. I cannot translate into those languages, my active command of them is simply too poor.

I enjoy translating. It’s like writing, only that you can fully focus on the technical aspects of it, since someone else already has done the thinking for you. If you like writing and have an interest in language, it’s a great thing to do.

LB: When I saw your work about sports and anti-fascism, I was a bit surprised, honestly. Normally, in the US, sports is run by and with nationalism. Often other ugly forms of chauvinism appear. Anti-fascist sports strikes me in many ways like anti-racist or communist skinheads: a rare exception or novel idea. What motivated you to work on and write about this? How has the work been received? Do you play sports yourself?

GK: I play a lot of sports and have always done so. Next to family and politics (which includes the work I do), sport is the most important part of my everyday life. This is also what motivates me to write about it.

Of course you are right, there is plenty of ugliness in sports, especially in the professionalised and commercialised varieties: competition, chauvinism, exploitation, unhealthy body norms, you name it. But sport is not only a big part of my life, it’s a big part of many people’s lives, and it won’t go anywhere in a liberated society, and neither should it, because there is plenty of beauty in it as well.

Essentially, sport is the combination of physical activity and play, which are both essential for our well-being. If the environment is right, sports can be great fun, they bring people together, and they teach us social values. The challenge for radicals is to create an environment that brings out the best in sports instead of the worst.

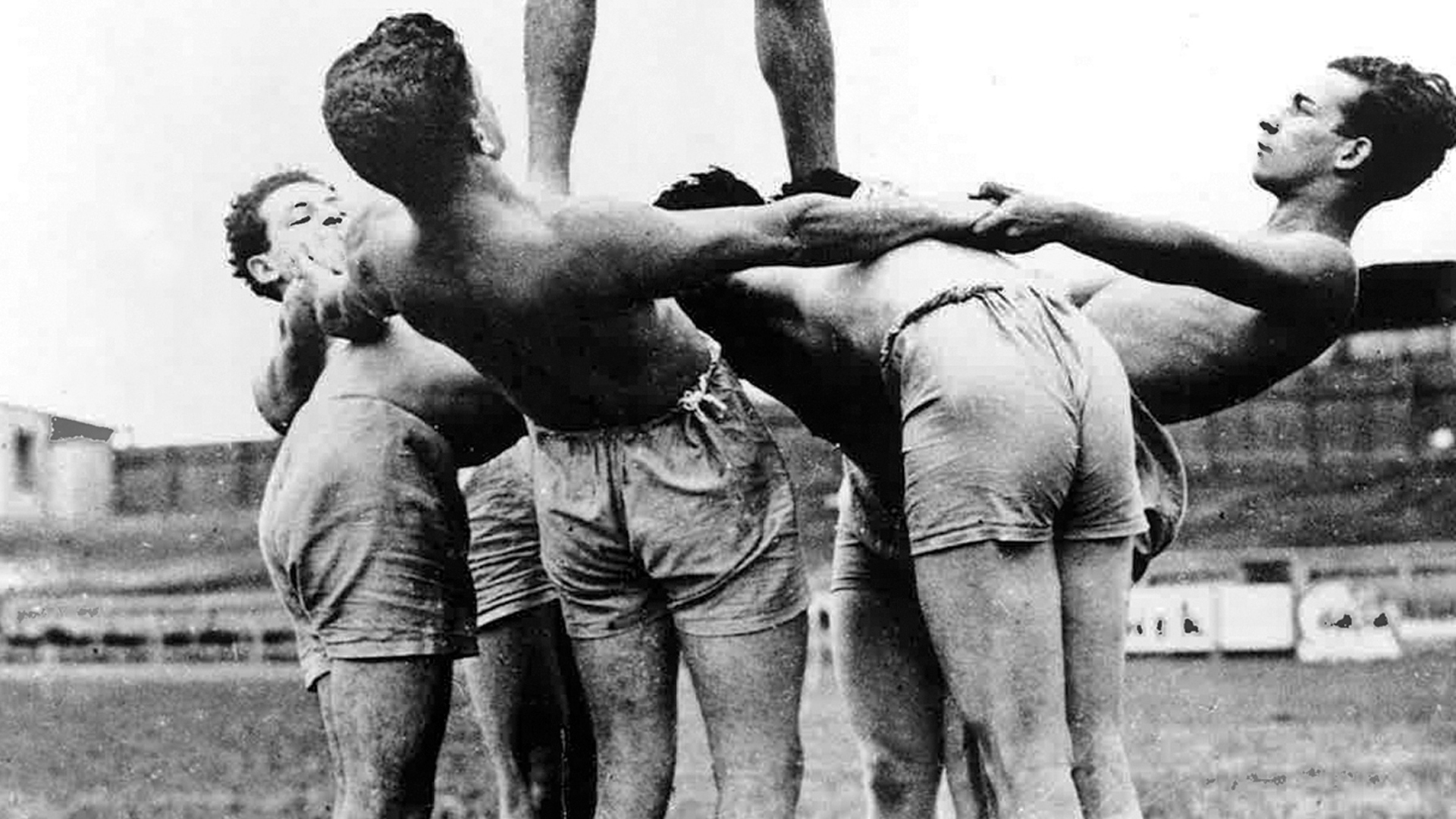

It is true that good examples are not always easy to find, but they exist: from the workers’ sports movement of the early twentieth century to sport’s role in the civil rights struggles of the 1960s to antifascist organising among sports fans today. Sport has tremendous political significance and the struggle for liberation needs to happen there as much as everywhere else.

The reception of the work I have done on the subject has largely been positive. Mostly, it’s read by radicals who share an interest in sports and find the stories inspiring. But I’ve also got nice feedback from people with no particular interest in sports who felt they had discovered new aspects of it.

Of course, there is the occasional critic who lambastes me for “misusing sports for political purposes”, but that has to be expected. For some people, addressing injustice is a distraction from having a good time, which they associate with sports. Sometimes, these people generally don’t want to hear about injustice, maybe because they themselves don’t experience much of it. But even for the exploited and the oppressed, sport can function as an escape and they don’t want to hear about politics in that zone. That needs to be respected, but in the long run, it’s not going to break the cycle where escape is the only way of dealing with injustice, which is never sustainable. I suppose the goal is having sports and politics being based on the same values, so that mixing the two will appear natural rather than contradictory. This, I believe, would be great progress.