By Elizabeth Hand

LA Times

August 6th, 2015

Mary Shelley usually gets mad props as the progenitor of feminist science fiction for her 1818 “Frankenstein; or, the Modern Prometheus.” But pride of place arguably goes to Mary Cavendish, who in 1668 penned a feminist utopian novel, “The Description of a New World, Called the Blazing-World,” in response to Robert Hooke’s “Micrographia,” which in 1665 put microscopes on the map and coined the biological term “cell.” Cavendish delved into speculation as to what might exist beneath and within the world we know, or think we know (alien life forms played a role). She was given the sobriquet “Mad Madge” for her pains.

Nearly 300 years later, things had improved … barely. “Women are writing SCIENCE FICTION!” trumpeted the flap copy for Margaret St. Clair’s 1963 novel “Sign of the Labrys.” Women, it went on to say, “are conscious of the moon-pulls, the earth-tides. They possess a buried memory of humankind’s obscure and ancient past which can emerge to uniquely color and flavor a novel.”

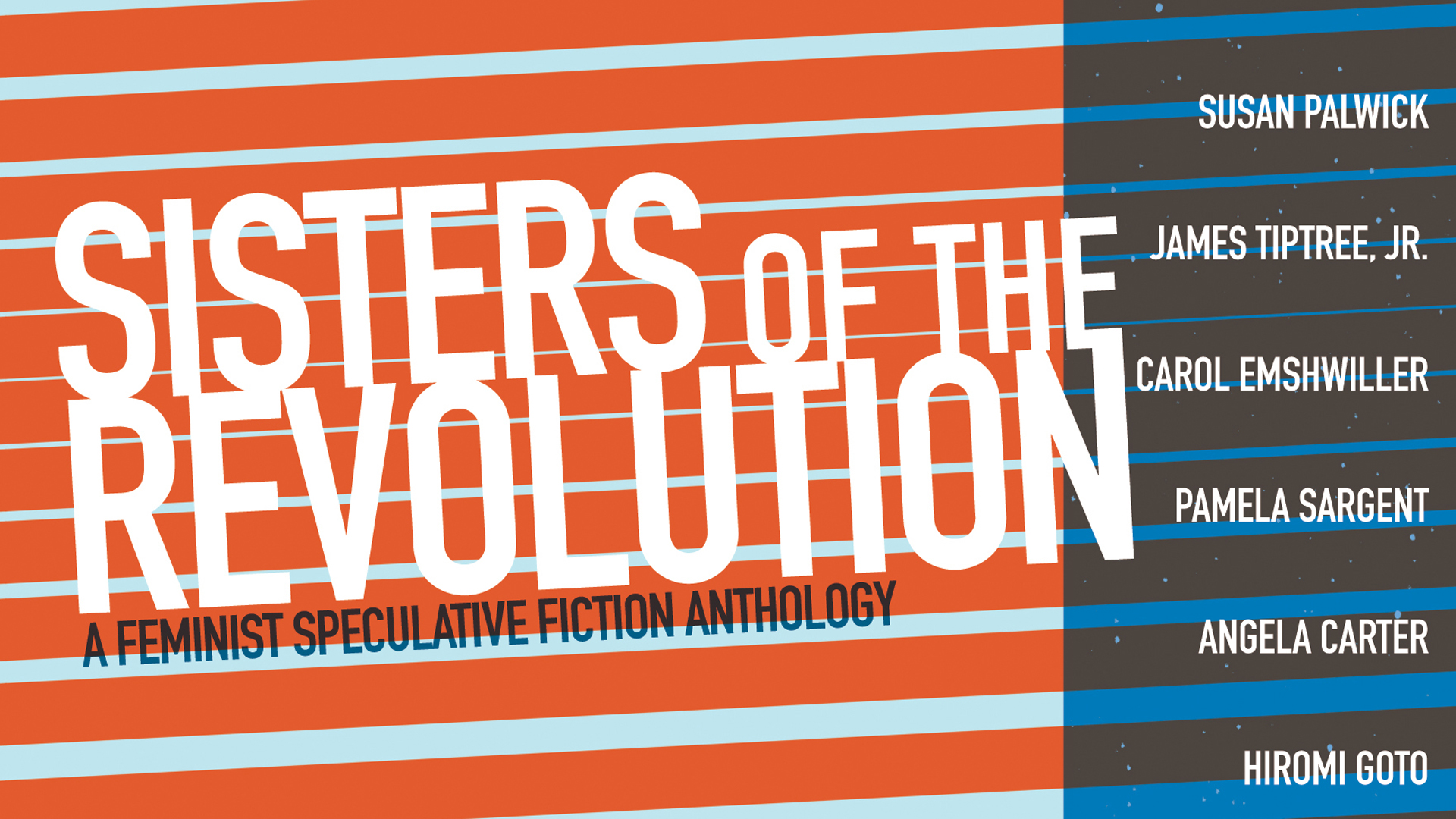

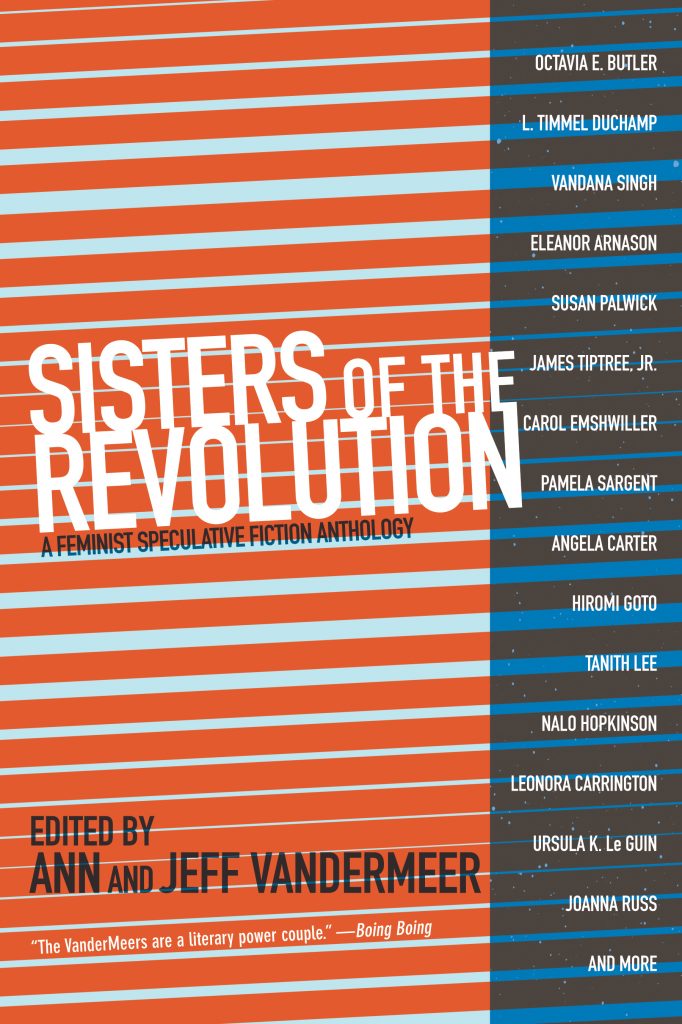

Those who don’t possess a buried memory of humankind’s obscure and ancient past are condemned to repeat it. So thank the Goddess for “Sisters of the Revolution,” a superlative new anthology of previously published feminist science fiction by female writers, edited by Ann and Jeff VanderMeer. Noted editors of numerous anthologies of speculative fiction, the VanderMeers have compiled one of the best volumes of feminist — or any other — science fiction in years. “Sisters of the Revolution” reaches back to the late 1960s and extends to 2012, with the lioness’ share of tales originally published between 1980 and 2000.

There are classic, much-anthologized stories by well-known writers here. “The Screwfly Solution,” a brilliant, terrifying tale of global femicide by James M. Tiptree Jr. [pseudonym for Alice Sheldon], carries even more impact in our own age of rampant violence against women than when it first appeared in 1977. An off-world feminist utopia confronts its own destruction in “When It Changed” by Joanna Russ, whose “How to Suppress Women’s Writing” was a touchstone for second-wave feminists. Ursula Le Guin is represented by “Sur,” in which a group of bluestockings mount an early 20th century expedition to Antarctica. “The Evening and the Morning and the Night” by Octavia Butler explores the global effect of a fictional neurovirus, and “how much of what we do is encouraged, discouraged, or otherwise guarded by what we are genetically,” as she states in her short afterword to this poignant tale. Angela Carter’s “The Fall River Axe Murders” follows Lizzie Borden on the sultry August morning of the day that her “Sargasso calm” notoriously erupts, suggesting motives that were ignored at the time.

But much of the pleasure in “Sisters of the Revolution” derives from encountering work by writers who aren’t household names. The stories are arranged as to how they “speak to one another rather than chronological order”. So Anne Richter’s “The Sleep of Plants,” deftly translated from the Belgian by Edward Gauvin, segues into Kelly Barnhill’s dreamy and dark magical realist tale, “The Men Who Live in Trees,” which slides into Hiromi Goto’s “Tales From the Breast” (“You want to yell down the hall that you have a name and it isn’t Breast Milk”).

Readers can also compare depictions of maternal love in Kit Reed’s viciously funny “The Mothers of Shark Island” and Nnedi Okorafor’s “The Palm Tree Bandit,” whose narrator tells her young daughter of her namesake great-grandmother’s daring nocturnal exploits, and delight in riffs on such oft-told tales as Kelley Eskridge’s gender-bending “And Salome Danced” and Nalo Hopkinson’s creepy Bluebeard story, “The Glass Bottle Trick.” And these are just a handful of the stories contained in this distaff treasure chest: Every single one is a gem.

Forty years ago, in her essay “American SF and the Other,” Le Guin wryly observed: “The women’s movement has made most of us conscious of the fact that SF has either totally ignored women, or presented them as squeaking dolls subject to instant rape by monsters — or old-maid scientists desexed by hypertrophy of the intellectual organs — or, at best, loyal little wives or mistresses of accomplished heroes.”

There are no squeaking dolls or loyal little wives here, no old maid scientists — and if there were, woe betide anyone who took them at face value.

Back to Ann VanderMeer’s Author Page | Back to Jeff VanderMeer’s Author Page