By Jane Sullivan

The Age

April 27th, 2018

Rita

is 15. She knows how to fight with her knees, her elbows, her teeth,

how to hold a blackjack, how to spot a cop, how to roll marijuana, how

to lure a man into a dark hallway.That’s the way they sold Gang Girl, a 1954 piece of pulp fiction from Wenzell Brown, author of Jailbait Jungle, Teenage Terror, Cry Kill and Teen-Age Mafia.

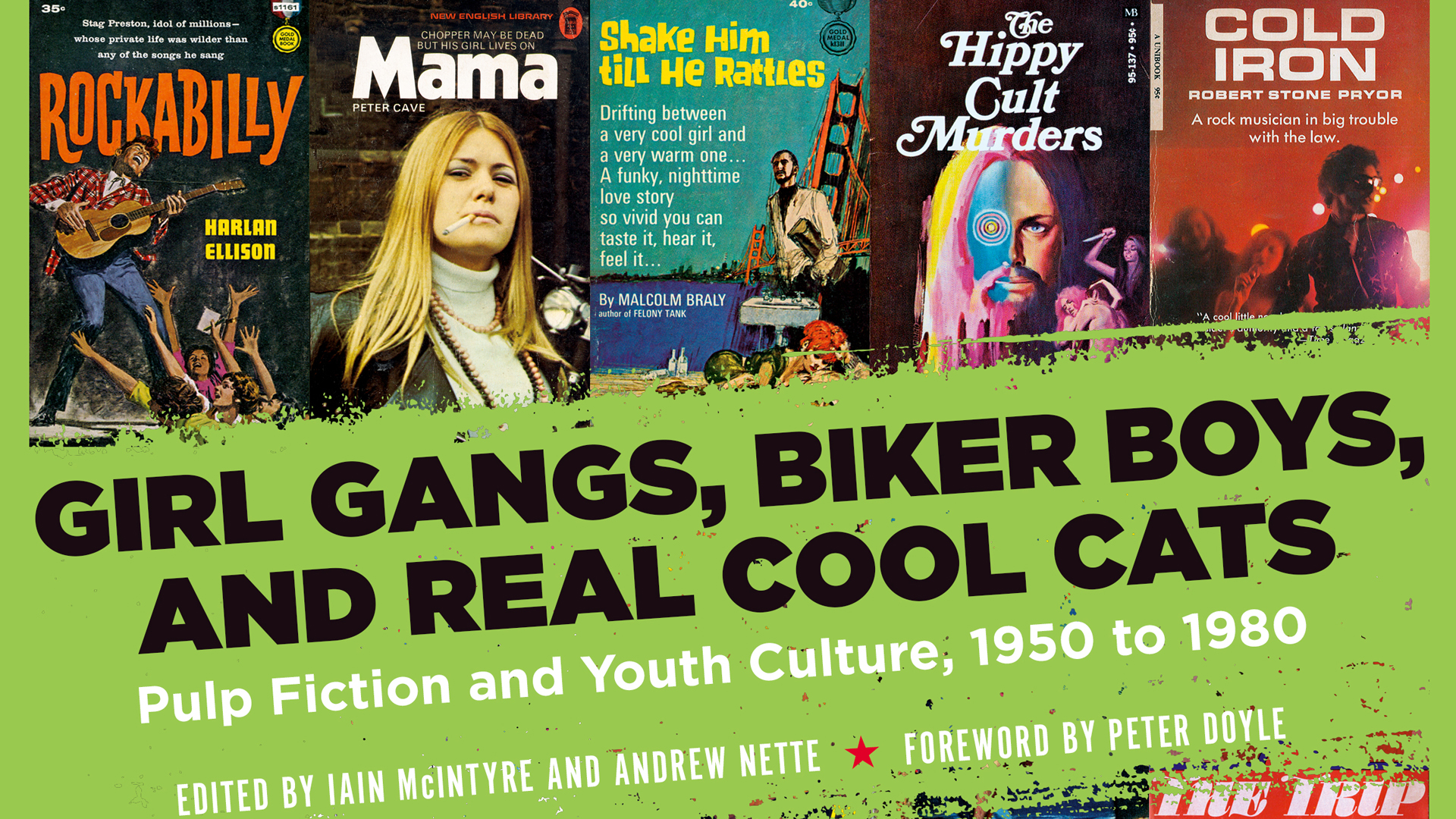

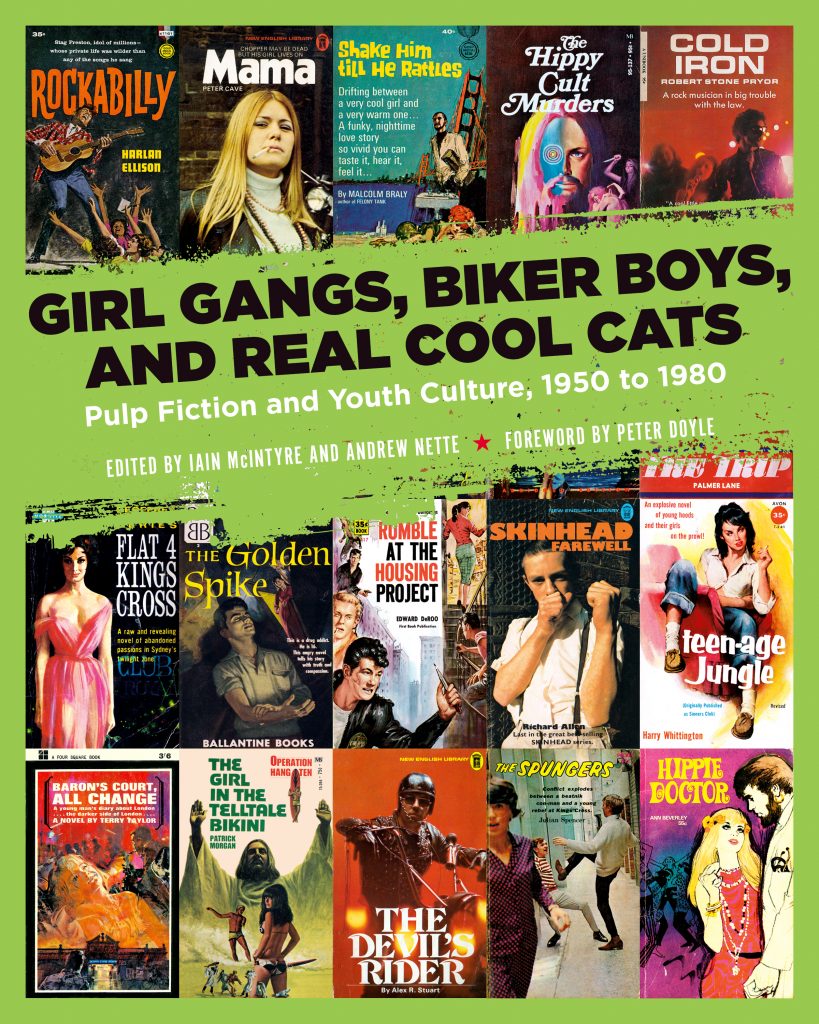

The covers of these cheap paperbacks are graced with lurid portraits

of young punks brandishing knives and sneering at the reader, and

vicious young women displaying large breasts in an aggressive manner. And nobody worries about blaming the victim: Jay de Bekker’s Gutter Gang

proclaims “They came from filthy slums – where even their dreams were

dirty!”Juvenile delinquents, they called them. In the conservative

1950s, the tabloids fulminated, shocked adults tut-tutted, and couldn’t

get enough of their stories. The arty end of this prurient fascination

produced James Dean, West Side Story, Jack Kerouac’s The Dharma Bums, William Burrough’s Junkie; the commercial end produced… well, pulp. I’ve been having huge fun reading about JD fiction and looking at the outrageously titillating covers in Girl Gangs, Biker Boys, and Real Cool Cats,

an anthology edited by two Australians, Iain McIntyre and Andrew

Nette. What was once reviled as rubbishy reading is now collected,

curated and revered as retro chic.

Youthsploitation sold, and went on selling for decades, until film and TV took over as the primary entertainments, and until the rise of young-adult literature, when teenage rebels were written about in an altogether more sympathetic way.

But before that there was a pulp procession of shocking kids: beatniks, hippies (best of all, murderous hippies), bikie gangs, rock stars, punks, skinheads and James Bond-style surfer spies.

Many of these books would make even Quentin Tarantino cringe, I suspect: they sound truly awful. But here and there I came across someone churning out quick books for cash who went on to make a more respectable name for himself. One was the science-fiction writer Harlan Ellison, who went undercover and joined a street gang as research for more than 100 stories and his 1958 debut novel.

He describes how he was later working as a reviewer and picked up a book from a box a publisher sent him. “It’s got this horrible, garish juvenile delinquent coming at you with a switchblade knife and it says Rumble. I thought ‘What is this piece of shit?’ and then I looked at the author and it was me.”

Not many pulp authors were women, but they often have the most interesting stories. The lesbian pulp novel, though a rarity, was particularly successful in the 1950s because it was such a taboo subject. Ann Bannon discovered her first lesbian novel in a pharmacy and decided to write one herself. She produced a series with suitably shocking but oddly euphemistic covers: the one for her novel Beebo Brinker describes the heroine as “Lost, lonely, boyishly appealing – this is Beebo Brinker – who never really knew what she wanted – until she came to Greenwich Village and found the love that smoulders in the shadows of the twilight world”. Bannon was married with two children. Her husband never welcomed her interest in such subjects, but he welcomed the royalty cheques. Her books have been republished and have been studied by a new generation of young scholars. She recalls a woman who told her that when she was young, she discovered a copy of Bannon’s novel Odd Girl Out and then went home to have dinner instead of jumping off a bridge. “Something like that really turns your heart over.”

Back to Iain McIntyre’s Author Page | Back to Andrew Nette’s Author Page