By Ernest Hilbert

The Washington Post

July 24th, 2018

In 1915, Charlie Chaplin, to the delight of moviegoers, created “The Tramp,” an enduring image of the sooty and bumbling yet lovable vagrant. Although distinctions were drawn between hobos and tramps, they were American migrants who hopped freight and passenger trains in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, some traveling in search of work, some others for less uplifting reasons.

“On the Fly,” an anthology billed as the first of its kind, guides us through the literature of “hobohemia” — the “jungles” (camps), “decks” (tops of passenger trains) and “main stems” (main streets) haunted by characters such as Sugar Butt Sam, Long Coat Lizy and Slicker Fastblack.

Editor Iain McIntyre has included writing from 1879 to America’s entry into the Second World War, by which time many migrants had taken to highways in automobiles. The tales and ballads demonstrate how hobos inspired both fear and envy in people trapped in domestic routines.

Popular portrayals such as Chaplin’s naïf belie just how literary hobos could be. Harry Kemp describes how he avoided jail a couple of times because sheriffs were awed “to find a tramp reading Shakespeare.” Meanwhile, in Glen Mullin’s white-knuckle tale of “riding the rods” — from his 1925 memoir “Adventures of a Scholar Tramp” — the author imagines the train passengers above him, who have no clue that “under their feet, hanging precariously to a rod, was a grimy hobo reading a socialistic pamphlet by Oscar Wilde.”

Women also rode the rails. Ben Reitman, writing as Boxcar Bertha, describes “the best known of the queens,” Lizzie Davis, who reminded him “of a great turbine engine, throbbing away. She had tremendous sex appeal, in spite of her hundred and seventy pounds and her ill-fitting, shabby gowns.”

Life on the road was not all adventure. Many accounts, such as Edwin Brown’s 1920 book “Broke: The Man Without a Dime,” tell of severe deprivation, including one tragic image of an old man lying on the ground, covered in tobacco juice, while vermin scampered around, feasting on last night’s dinner scraps.

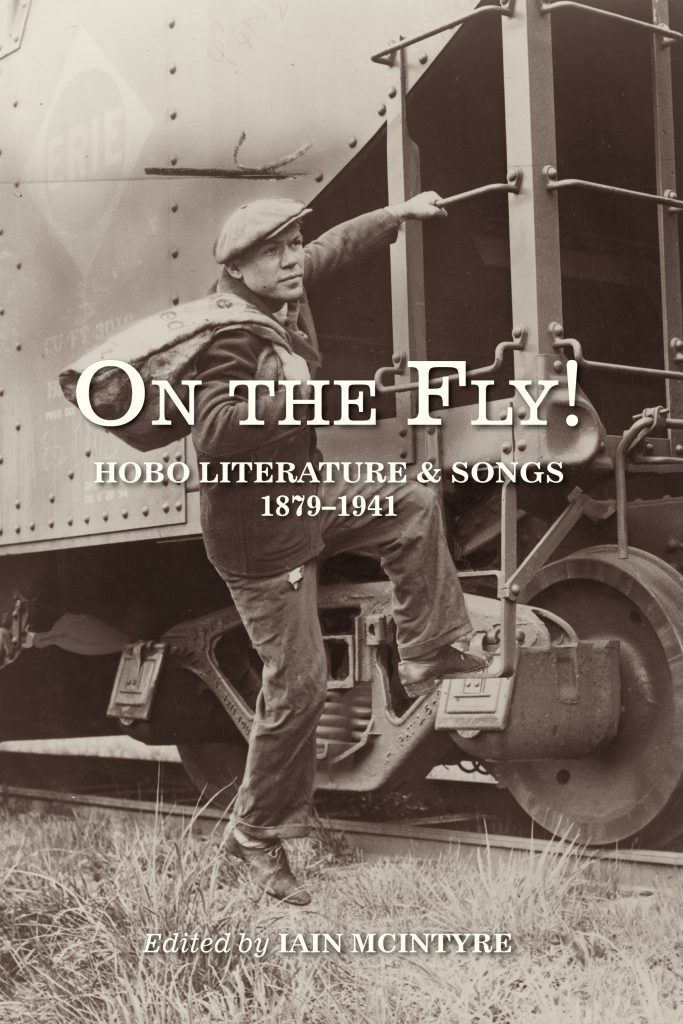

Men ride on the “pilot” or “cowcatcher”of a train in the 1890s. (Courtesy of PM Press)

Morley Roberts, one of several English writers who “tramped around” America in search of material, wrote in 1904 that “America is a hard place, for it has been made by hard men . . . the unconquerable rebel, the natural adventurer, the desperado seeking a lawless realm.” Starting in the 1890s, Jack Black spent grueling years as a thief and opium addict before becoming a librarian and writing such books as “You Can’t Win,” a model for William S. Burroughs’s “Junky.”

African American writer William Attaway — who would go on to write “Day-O (The Banana Boat Song)” with Harry Belafonte — describes horrendous conditions for a group of travelers in 1919, during the Great Migration. He reports that migrants “squatted on the straw-spread floor of a boxcar, bunched up like hogs headed for market, riding in the dark for what might have been years.”

Hobos of all kinds avoided the American South, where they were often rounded up and placed in forced-labor camps.

Who were these men exactly? Some dreamed not of freedom but of “standing at their machines in their factories . . . lined up at the office window on pay day.” For others, life “on the fly” was not about excitement or employment. Writer and transient Henri Tascheraud describes those like him as “for the most part throwbacks, pure and simple. We don’t fit, and that is why we love vagabondage, and disdain respectability.”

McIntyre includes lyrics to folk ballads, protest songs and blues songs, the most affecting being those like “Big Rock Candy Mountain,” which yearns for a promised land “where all the cops have wooden legs . . . and the hens lay soft-boiled eggs.”

The spirit of these roving authors lived on in Jack Kerouac’s restless dreamers, Kris Kristofferson’s “Me and Bobby McGee” and Jack Nicholson’s drifter Bobby Dupea in “Five Easy Pieces.”

In an era when tent cities spring up in prosperous American metropolitan areas, the lives captured in “On the Fly” feel less comfortably distant than we might like. That is perhaps why the best of these classic accounts of “bumming around” retain all their simmering anger and desperate optimism.

Ernest Hilbert is a poet and dealer in rare books.

Back to Iain McIntyre’s Author Page | Back to Andrew Nette’s Author Page