By Michael Jongen

Newtown Review of Books

January 24th, 2019

In his introduction to this fascinating collection of writing from the American hobo era Iain McIntyre tells us how that way of life, which began due to economic necessity, became so much more.

The material gathered in On the Fly! reflects the politics of the early 20th century and the decision by many people to opt out of mainstream life and seek an alternative to work in the factories. In hopping the trains, McIntyre notes that many middle-class and upper-class men and women also rebelled against bourgeois ideals – or at the very least sought adventure. The hobo life also gave gay and bisexual men a subculture where their sexuality was often accepted.

Hobo literature first began to be noticed, and published, at the turn of the 20th century. Many of the early hobo writers wanted to reshape their image as bums and vagrants. The movement began to become political as agitators sought to reframe hobos’ experience as victims of the economic order. Other writers, however, sought to celebrate and romanticise them. Many works were often parodies that mocked the hobos’ enemies.

Jack London is the most famous

name from this period. London was a socialist who credited his years of

living as a hobo for converting him to the cause. He used his articles

to condemn capitalism, but his writing also encapsulated the spirit of

hopping the trains. The hobo writing that followed emulated London’s

approach, seeking to collect in print the tall stories that were often

heard on the road. At this time, adding to the increasing number of

works of memoir and fiction being published, sociologists, reformers and

criminologists began writing about hobo life.

McIntyre’s

Introduction is a fascinating and informative history of the movement,

and as editor he has curated a marvellous collection of writing

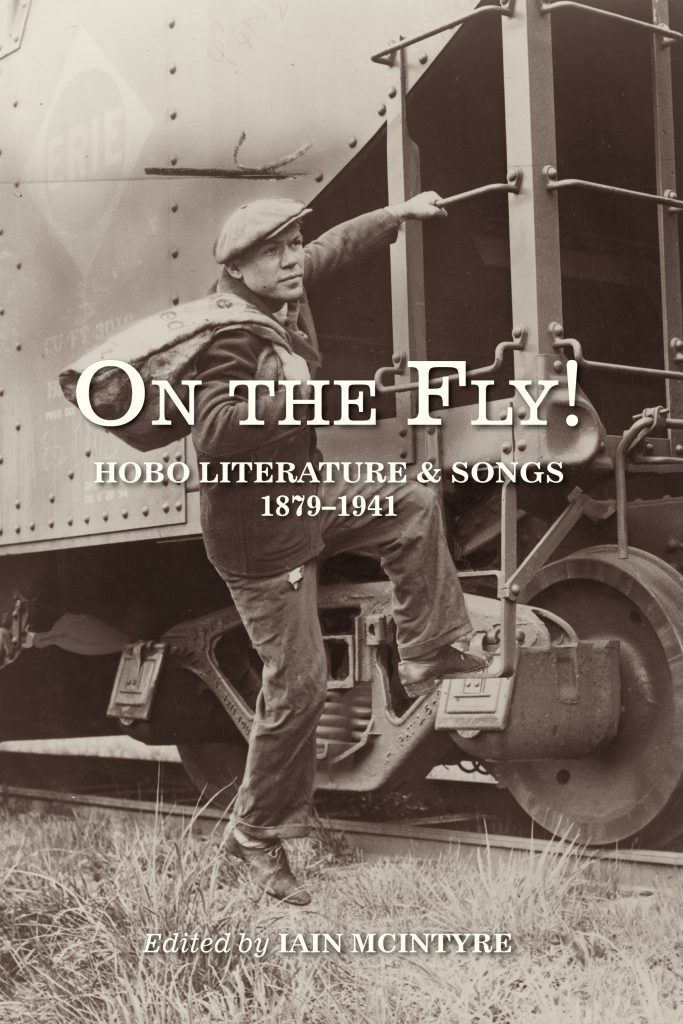

including memoir, fiction, poetry, lyrics and polemic. The book is also

illustrated with evocative photographs and memorabilia.

The extracts from novels and memoirs define the era with a variety of experiences, from the politics of the International Workers of the World (the IWW) to the personal stories of young people setting out on the trail.

‘In Partnership with a Burglar’ by Leon Livingstone (‘the Rambler’) is an extract from one of the ten books he published between 1910 and 1921 based on his own experiences as a hobo. A young man has just set off on his journey when he meets up with ‘Frenchy’. The two join a group of men:

‘Chase yourself, you gaycat! Go and work for your matches,’ was the reply he received, and a look showing how disgusted Frenchy was even to talk to the man.

Frenchy took me to the other side of the tank and said: ‘Kid, I don’t want you to mix with these “gaycats”.’

I inquired what he meant by ‘gaycats’, and he commenced to laugh. ‘You have been traveling the “pike” for a solid year, and you don’t know what a “gaycat” is? Get out, Kid, you are joshing.’

I told him I did not know, and then he explained to me: ‘A gaycat,’ said he, ‘is a loafing laborer, who works maybe a week, gets his wages and vagabonds about, hunting for another “pick and shovel” job. Do you want to know where they get their monica [nickname] “gaycat”? See, Kid, cats sneak about and scratch immediately after drumming with you and then get gay

That’s why we call them “gaycats”.’

Hobo literature wasn’t just about the men. Sister of the Road: The autobiography of Boxcar Bertha was a fiction written by Ben Reitman in 1937 based on the experiences of three women he knew. After meetings on the streets or at Bughouse Square in front of Newberry Library, crowds of speakers would gather at sympathetic cafes or in homes of friends:

Many of the lesbians hunted in packs and travelled in automobiles. There was a group of these who had a magnificent apartment on north Dearborn Street near the Park. I met a dozen of them there at a soiree called ‘Mickey Mouse’s party’. Half a dozen of them were wealthy women. Four of these were legally married and two of the four had children. They were there ostensibly as sightseers, but actually they had more than a superficial interest in these lesbian girls. But they were constantly being exploited. The lesbians would get their names and addresses and borrow money by saying, ‘I met you at Mickey Mouse’s party.’

Jim Tully ended up working as Charlie Chaplin’s publicist in the 1920s, and there is photo of them together opposite the following extract from his ‘Thieves and Vagabonds’ published in 1928 in American Mercury.

A group of bored and hungry men listen as One Leg describes his new invention:

‘A

dog-fooler,’ answered One Leg, pulling up the trouser of his remaining

leg and showing the calf of it wrapped about with heavy brown paper.

‘There ain’t a dog in this country can bite through that,’ he said

proudly.

Husky felt the paper and exclaimed, ‘Gosh, it’s only paper!’

‘Sure! What did you think it was – cement?’ One Leg snarled.

‘Well, a fellow needs somethin’ like that – there’s a lot of dogs in Michigan,’ commented a vagabond.

‘Well I ain’t fast on this one leg,’ resumed the inventor, ‘so I had to rig up somethin’ to protect it.’

‘I’ll bet a Newfoundlan’ kin bite through that,’ said a vagabond who had not spoken before. ‘I’ve seen ’em up in Maine bigger ’n cows.’

‘How about a bulldog?’ asked another.

‘Oh they can’t bite real very hard,’ answered One Leg. ‘Their jaws don’t open very far – it takes a big mouth for a hard bite.’

‘A collie’s mean, though,’ ventured Husky. ‘They’d bite their uncle if he wasn’t lookin’.’

‘Them little terriers are pine to me,’ said a nondescript. ‘They don’t bite so hard, but they raise old Ned till they git all the darn dogs in the neighborhood after a guy.’

Husky looked bored. ‘Let’s forgit about dogs,’ he said. ‘Doc don’t care about dogs, do you, Doc?’

The

writing is always gritty and authentic, the stories fascinating. Poetry

and music were also favoured tools of the propagandists and writers of

the era – for example, the poem ‘The Gila Monster Route’ describes a

hobo waiting to jump a train on a terrible and dangerous railroad.

There is a great deal going on here, from poverty and desperation to the seedy glamour to the politics to the mystique of the lifestyle, and there is much to be gained from this collection. It is clear that this movement is an important part of America’s history and has informed popular culture in particular. Iain McIntyre has introduced us to the ‘lost voices of Hobohemia’. As we read this remarkable history, it is difficult not to reflect on American artists such as John Steinbeck, Kerouac, Joan Baez and Bruce Springsteen who have carried on these traditions.

The illustrations and photographs and printed paraphernalia that accompany the pieces are well-chosen, and this is a well-produced book that invites dipping and browsing.

A remarkable anthology.

Back to Iain McIntyre’s Author Page | Back to Andrew Nette’s Author Page