By Peter Doyle

The Conversation

May 10th, 2018

That Sergeant Peppers album cover

roll call of heroes seems a rather quaint exercise now. We’ve still

got lists of heroes and anti-heroes but indie culture watchers and

streetcorner critics have long since worked their way past the big

figures like Elvis, Marilyn, Marlon and so on to people and places

further out and further down.

Cinephiles have combed the ranks of B-grade directors, low-rent auteurs and semi-forgotten character actors, working down to low rung schlockmeisters and trash merchants. Age of Rock geeks and music journalists forever trawl through little-played B-sides, obscure old jukebox records, the dusty outputs of small and regional record labels. Likewise, fans and collectors of pulp publishing continue to produce entire new canons and anti-canons of shadow literatures, starting with hardboiled and noir crime, and moving on to every possible sub-form.

The term “Pulp Fiction” refers to what is actually a sprawling category of cultural product, covering a wide range of mass publishing enterprises, mostly of the mid-20th century. There are competing definitions, but generally the term “pulp” is used to include magazines, comics, paperback novels, novellas, non-fiction books and booklets, cheaply printed on low grade paper, often in monstrous print runs, sold at newsstands, railway stations, corner shops, or distributed to armed forces, with the cheapest possible cover price – a dime in the US, sixpence or a shilling in Australia.

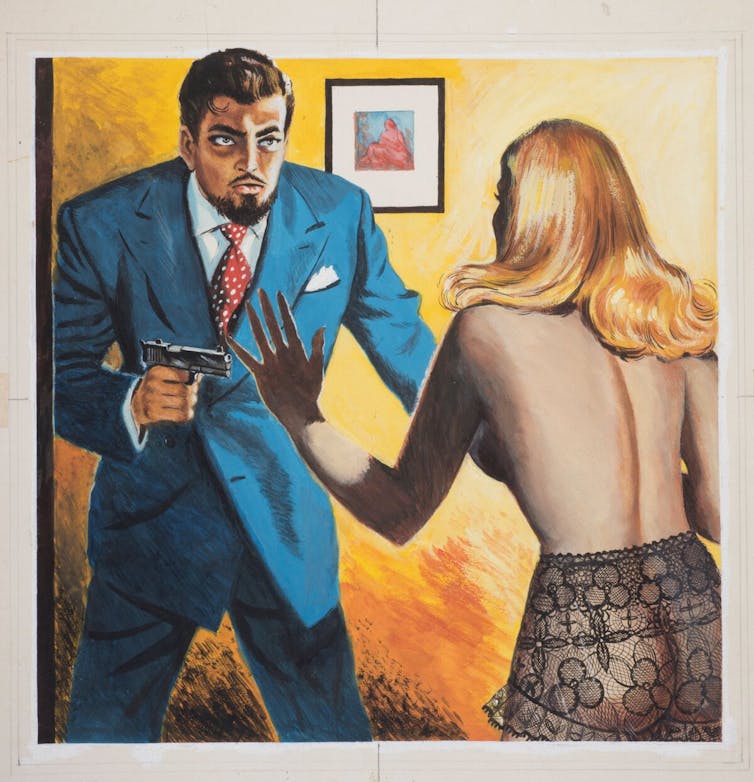

Product was offered up to the savagely Darwinian competition of the newsstand, with new titles appearing constantly. So pressure was always there to hype up cover illustrations, with saturated colours, sexy or even pseudo-pornographic illustrations.

Pulp was the natural home of genre narrative: science fiction, crime, romance, westerns, horror and “weird” tales, and nearly as much (purported) nonfiction, in the form of true adventure and crime stories and bogus ethnography of the shocking-exposes-of-carnal-practices-in-exotic locales type.

We’re talking trash, exploitation, flagrant misrepresentation, tastelessness, and a general striving for pure textual energy. With a high premium on visuality. Plenty of splash, bang, pop and shock, pushed to the limits of acceptablility. There’s a lot there to love.

Like B-movies and rock’n’roll, pulp culture mostly came from the USA, with a substantial British contribution, and those two suppliers between them pretty thoroughly colonised Australian markets. But not totally: since the late 1800s there had been a trade in locally made paperback reading matter (such as the then scandalous “bushranger stories”, which were said to be inflaming urban delinquents to rebellion and lawlessness).

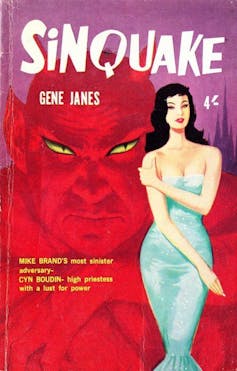

When the supply of US comics and paperback trash was abruptly halted in World War Two, local publishers rushed to fill the gap, offering hastily conceived superhero comics, crime magazines and a range of sexy novels. (The text rarely matched the salacious promise of the cover.) The content was nearly entirely Australian, providing a living or at least some extra pocket money for a bunch of artists, letterers, young wannabe authors and quite a few moonlighting journalists. It was the 1940s precursor to today’s gig economy.

A handful of local pulp publishers, mostly centered in Sydney limped on through the 1950s, fending off as best they could competition from bigger, bolder, newer and cheaper US product. Newsagent shelves of the time displayed racks and racks of material – much of it locally made – with some surprisingly raunchy cover art, and bold strap-lines promising lurid content within. (Australian pulp factories rigorously observed a few simple rules: show as much feminine breast and cleavage as possible, for example, but use careful shadows to hint at – never directly show – a nipple.)

Australian adaptations

The life of the freelance creative artisan was precarious anywhere, but in Australia it had its own special circumstances. Britain and the USA had populations large and dense enough to sustain entire industries devoted to all aspects of pulp production, often concentrated in specific districts. It was a much riskier game in Australia, with its dispersed population and smaller markets.

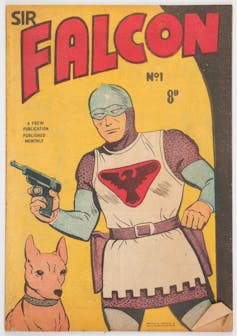

Still creative labourers did their thing, albeit in semi-isolation. Product was made and distributed; ideas, styles, genres, riffs, and tropes were adapted for local audiences, often crudely but sometimes brilliantly, or at least energetically – like the wonderfully odd, now highly collectible comics produced by Frank Johnson Publications and Frew Publications in the 1940s and 1950s.

Foundational researcher Toni Johnson-Woods and more recently Andrew Nette and Kevin Patrick are building a growing and diverse body of research into the mysterious world of Australian pulps and comics. They move smoothly from assessments of the works themselves (often affectionately ironic in tone), to biographies of forgotten artist-authors-makers. (Very few of Australian pulp writers, it turns out, could ever afford to give up their day jobs, as journalists, school teachers, accountants whatever, or in the case of prolific author of westerns and detective stories, Gordon Clive Bleeck, a railway worker.)

The spotlight has recently turned to the entrepreneurs themselves – those fleet-footed, sometimes ruthless small businessfolk who by turns scammed and flattered their contributors and managed the government censors and risk averse national distributors, while keeping a sharp eye on trends and fads.

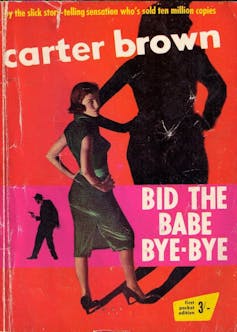

The survival of a local pulp industry at all is something of a wonder. Nearly anyone who was alive in 1950s or 1960s Australia will remember the ubiquitous, 300- plus series of detective novels written by “Carter Brown”, with their titillating cover art, carefully placeless, or explicitly US setting, written by a prolific local author Alan Yates. Publisher Horwitz indeed managed to turn the series into a lucrative export.

A few years ago I was invited to put together an exhibition drawing on the sprawling papers of Sydney pulp outfit, Frank Johnson Publications, held at the State Library of NSW. The original idea had been to simply display the racy cover art and true crime illustrations, but my attention was also drawn to the volumes of correspondence between Johnson and his far flung network of authors, journalists, artists, illustrators. Whole working lives were revealed, if obliquely, in the nitty-gritty back and forth between Johnson and his schleppers. There was hope, disappointment, rejection, self-doubt, anger, sometimes a certain neediness, other times outright manipulation, and occasionally, great dignity.

A Peter Chapman cover for My Love, a 1950s collection of romance fiction.

It became clear too that for some freelancers, there was a living to be made. The late Peter Chapman, for example, was a comics author, cover artist and general illustrator who got his start as a teenager freelancing for Frank Johnson in the 1940s (at “30 bob a page” – pretty good money for the time), and went on to make a lifelong, four decade-plus career of it.

As well as possessing an appealingly loose but accurate line and a vibrant sense of colour, Chapman had storytelling nous. He authored a number of successful “true pirate” and superhero comics and invented the “Sir Falcon” character – a pistol-wielding medieval knight. His later western and war novel covers always retained a strong sense of unfolding story, often deftly encapsulating the narrative pivot-point.

Lost in pulp’s crazy labyrinth

For the contemporary reader, the pleasures of pulp are complex and contradictory. Start digging and it is possible you’ll find unexpected literary finesse – plenty of people who eventually graduated to high literary respectability, such as David Markson, paid the bills early on by writing serviceable pulps. The early work of Patricia Highsmith and William Burroughs first appeared in very pulpy editions. And there were plenty who never graduated, but whose work ranks high on modern literary criteria: balance, flow, economy, freshness of image and language. Natural writerly grace and all that stuff.

A locally made Peter Chapman cover for a licensed pulp collection of US Detective Stories. Author provided

You might find earlier versions of the punk aesthetic – the textual equivalent of harder, faster, louder. Pulp fictions regularly managed to be way more out there. Because no one was paying all that much attention. There wasn’t time to sand down the sharp edges.

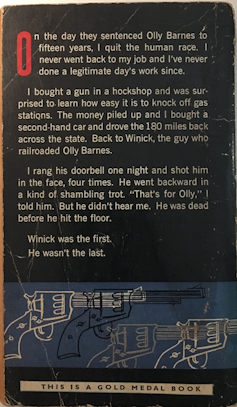

I’m not a collector of any stripe, but I’ve done my time in the second hand shops, and have my own beloved finds, among them Dan J Marlowe’s, The Name of The Game is Death, from 1961, with its great cover art and back cover text which is almost rock’n’roll poetry in its own right – “On the day they sentenced Olly Barnes to fifteen years I quit the human race. I never went back to my day job and I’ve never done a legitimate day’s work since.” The novel is fast, the prose spare, but never rushed. The first person narrator is a sort of psychopath with principles. The story has three different time frames, and the switches are deftly handled. The plot is totally uncompromising. One of the story strands brilliantly narrates the character’s humdrum middle-class childhood, and his emerging outlaw weirdness. The author himself turns out to be a dark and enigmatic figure.

Blurb on the back cover of The Name of The Game is Death.

But pulps that stand the test for literary value are relatively rare. You might more commonly read them as symptom, to see laid bare the unspoken fears, desires, dreams and nightmares of the time. Doubly, trebly so when it comes to sex and sexuality. Among the preoccupations of 50s smut pulps there’s a dogged and recurring fascination with queerness, lesbian sex, bondage and sadism, gay sex, teen sex. Pulp as cultural Freudian slip, loony bulletins from the collective Id. Maybe not so loony.

Or you might say to hell with that, and just go with the flow, enjoy pulp for its couldn’t-give-a-shit attitude. There’s deep, dark, perverse mad – the amazingly twisted noir novels of Jim Thompson for example – and then there’s fun mad. John Franklin Bardin’s wacko novels (such as The Deadly Percheron) are the sort of mad that the author is complicit in.

And then there’s the naïve and unselfconscious, weird obsessive, medication-all-wrong mad, the kind the artist seems to be entirely unaware of. Great, but tormented US pulpster David Goodis, favourite of the French Nouvelle Vague might qualify, as might Richard Allen, British author of bovver boy youthsploitation classics including the much revered Suedehead.

Fossicking

Most cultural product – be it high, low or of the middle, nobly or cynically intentioned – sinks quickly into obscurity; headed for the dump, unread, unseen, unheard and uncelebrated. Live fast, die young etc.

Which means there’s a lot there for the latter-day cultural ragpickers. It’s not that easy to spot the diamonds in the rough. Most of us need a gently eye-opening pointer now and then in order to see the value. It takes a lot of work and a lot of time spent combing through junk shops, flea markets, eBay sales. It can be gruelling. You can find yourself soon hating everything – yes, it’s called trash for a reason. More scarily, a kind of rapture of the deep can set in, and you start loving everything. Finding virtue everywhere.

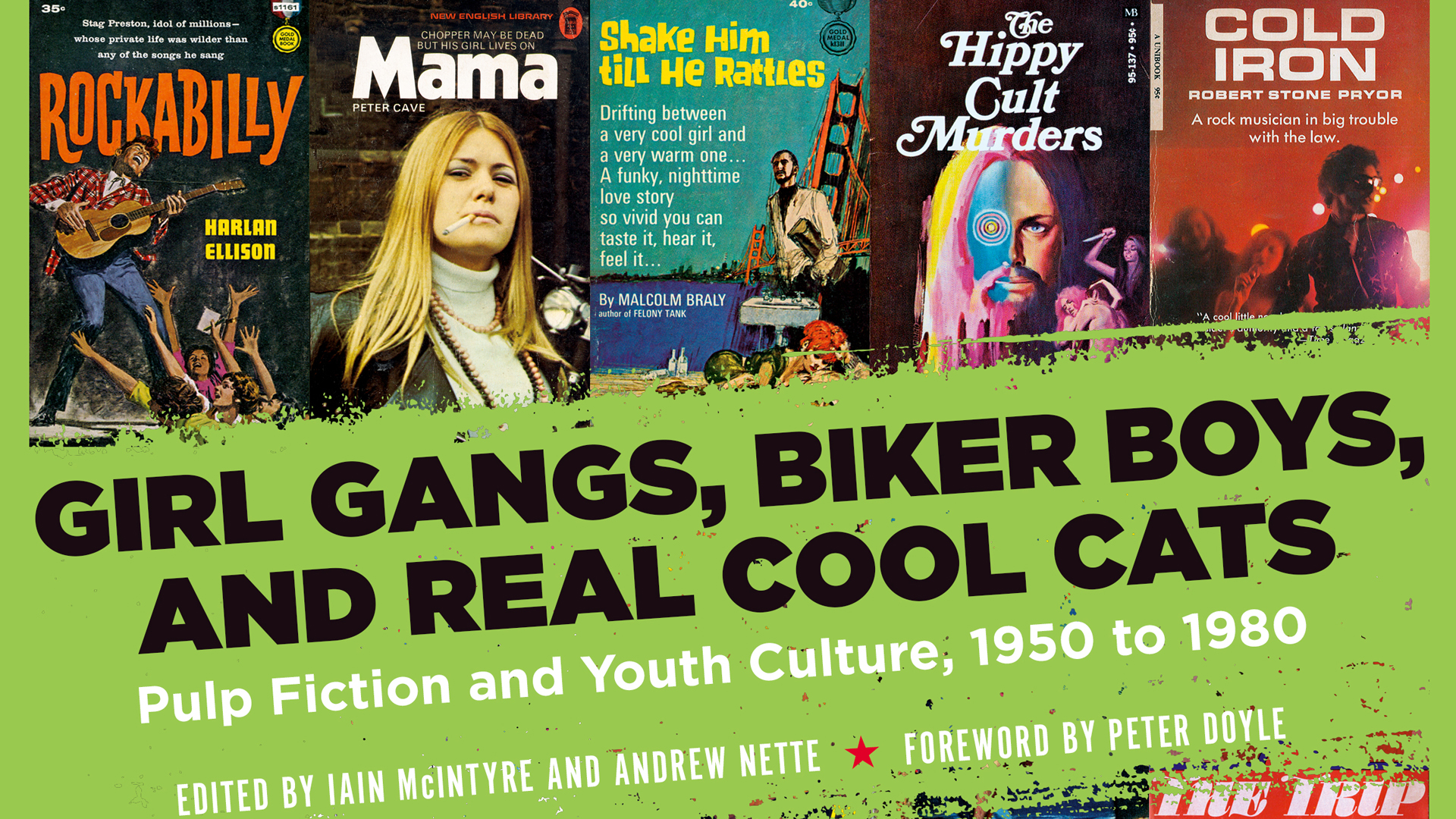

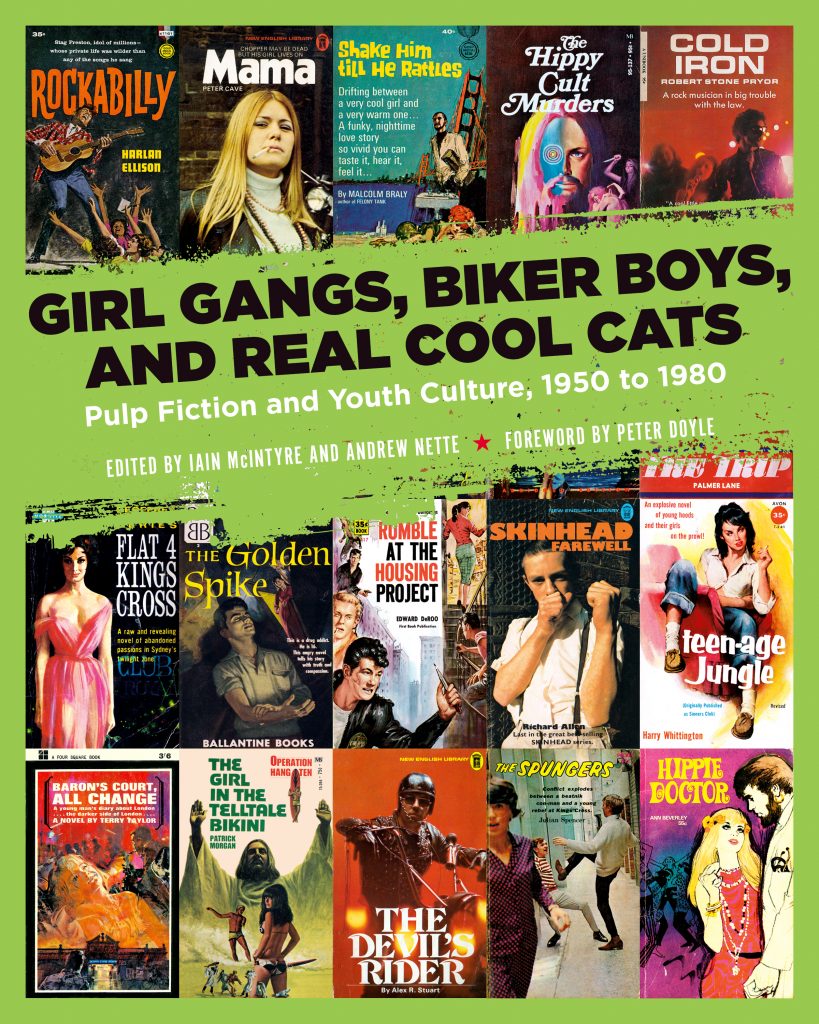

A recently released collection, Girl Gangs, Biker Boys, and Real Cool Cats: Pulp Fiction and Youth Culture, 1950 to 1980, edited by Melbourne-based researchers, Iain McIntyre and Andrew Nette, shows wonderfully how trash can change, how new riffs can quickly emerge. How our contemporary understanding of it changes and evolves and how much careful husbanding and thoughtful interlocution the whole process demands. (Disclosure: I wrote a foreword for the book.)

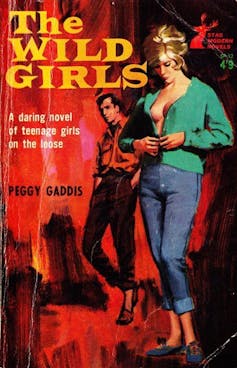

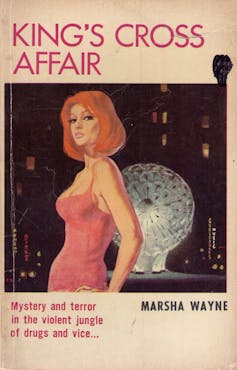

It’s an old story now that successions of youth subcultures, each more bad mannered than the one before, provided so many of the panic refrains of post war public life in the west, publicised by ad hoc alliances of tabloid journalists, social workers and media commentators. In the early 1950s it was juvenile delinquents. Then came beatniks. And bikers. Gays and lesbians. Hard dope fiends. Later on hippies and countercultural types, mods, rockers, surfers, skinheads, revolutionaries. Trippers, potheads and ravers. Rock musicians and groupies. Portrayed as a kind of tribe, obviously. With secret rituals, which most likely involved something sexy and forbidden.

So, that’s a promising set of circumstances for the low-end fiction factories of the day: there’s anxiety mixed with genuine curiosity mixed with sexual frisson. The cheap paperback industry knew how to churn out some appropriate product. Nette, McIntyre and their contributors have assembled a dizzying catalogue of fascinatingly tawdry exploitation lit: stories about dark and forbidden doings among secret enclaves of artists, dykes, bikers, drug addicts, jazz musicians and the like. Novels would typically tell of an ingenue drifting into some cultish social underworld and being initiated into its forbidden practices. It would usually end with the ingenue’s ruination and death, often by murder or suicide.

But the ground started shifting. Pulps in the 1950s and 60s had typically depicted the “other”. The people on the train to work who read about lesbians bikers or boho artists or ghetto dope fiends probably weren’t part of those groups, and that separation of domains was core to the cheap kicks the books delivered. But during the golden age of “tribe” pulps, the tribes themselves went from being weird and marginal to being visible and even central to global cultures.

By the early 1970s there was nothing very exotic about long haired young people who smoked dope, shared houses, played in bands and slept with one another. Queerness and genderbending were moving rapidly towards mainstream visibility, and the idea of “youth gangs” had lost much of its terror-clout.

A typical old school pulp writer might have been a World War Two veteran, maybe, or a middle-aged literary lady, turning their unsympathetic gaze to some upstart, youth craze or other. But by the 1970s that pulp author might be a pot smoker or tripper, a surfer or a hippie chick. Maybe of non-mainstream sexual orientation. Or a New Left sympathising, anti law and order, social change person. Or a crazed gun-toting survivalist. While that might help the authenticity, it could compromise the prurience.

Second life

Pulps through the 1980s went on to embrace ever more violent Serpico and Rambo-styled revenge sagas, as well as super tooled-up espionage, Mafia, mercenary and paramilitary adventure yarns – often with a massive gun barrel represented in hyper-perspective on the cover. Fans continue to debate where pulp went from there – maybe the internet simply consumed it.

So when that early material gets rehabilitated there’s a lot to deal with. There’s the whole artefactual package: cover art, strap-lines, back page, title font, colours, design. There’s the text content – the story itself. (Do we just go with it, or do we keep our distance, botanize it. Like a weird specimen?) And the author, should their life and career be attended to. Is it of interest? (Often resoundingly, yes.) And we might consider, or just enjoy the clever ways the whomp of the visuals interact with the wham of the story.

You could argue that pulp material culture is a direct precursor to the clickbait aesthetic. Digital screen culture is reconfiguring how image, design, text and story interact. Some media theorists believe this is way more than simply advancing the fashions and practices of design and publishing, but in a much deeper way is remaking the ancient distinction between “pictures” and “writing”. Looking at the work of pulp illustrators and comics makers of half a century ago we can see that they were quietly and cleverly dealing with the myriad problems, tensions and artistic opportunities that are commonplace today.

It takes a nuanced understanding, and a huge amount of time and energy to bring all that together for the time-poor modern reader. And to see the glimmerings of value there in the first place. To recognise that a thing can change: a thing which last month was junk, really was junk, has quietly become something else.

A selection of Peter Chapman’s art is the subject of an exhibition at Macquarie University Art Gallery, 16 May-29 June 2018.

Back to Iain McIntyre’s Author Page | Back to Andrew Nette’s Author Page