by William A. Pelz

Labor Studies Journal

June 2012 37: 236-237

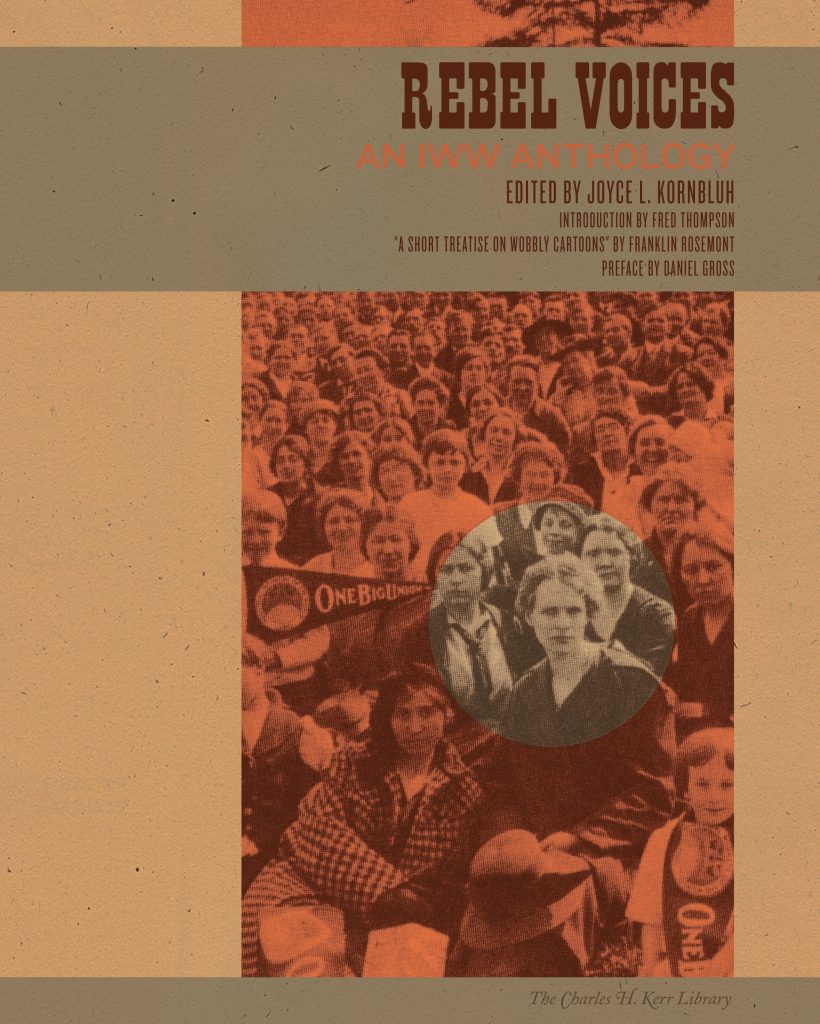

Born in 1905, the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) at its height organized hundreds of thousands of workers to create a type of solidarity unionism that included women, minorities, and immigrants, all of whom have been too often ignored by mainstream labor. Although the IWW has yet to build the “One Big Union” of its dreams, it has nonetheless been an inspiration for generations of workers and radicals. In Daniel Gross’s preface to this new edition of the long-out-of-print 1964 edition, he claims that this is “the most important book ever written about the Industrial Workers of the World” (p. ix). Although a bold statement, there is much truth in it, because Rebel Voices is a fine collection of original source material written by IWW members themselves. Naturally, this means there is no pretense of objectivity or detached analysis. Yet it allows the reader to feel the passion that drew so many to the organization. By including a rich collection of cartoons, posters, and other graphics, this anthology is lively, informative, and at times, inspirational.

While most chapters appear mainly of historical interest (e.g., “Patterson: 1913”), the material gives a clear sense of the ideas that motivated IWW members and supporters. Starting from the premise that the “working class and the employing class have nothing in common” (p. 12), the IWW put forth a class-struggle vision of unionism. Placing great importance on democracy and direct action, it challenged more traditional trade unionism. Believing that unions based on craft needlessly divided the working class, the IWW was a pioneer in the development of industrial unionism before the CIO was even conceived.

With seditious humor and biting satire, Rebel Voices

brings alive the revolutionary syndicalist challenge to both the

capitalists and mainstream trade unionists. One need not agree with the

arguments made in this book to find them thought provoking. Further, the

book advances the claim that the work of the IWW has helped protect

civil liberties. The IWW was a leader in the fight for free speech in an

early-twentieth-century America, where verbalizing opposition to the

status quo was all too often a criminal offense. When the First World

War struck, the IWW was clear about which side it supported. The IWW

argued that it was on the side of workers being forced to kill their

fellow workers for the benefit of the employing class. This was a

courageous

position that opened the already persecuted group to even greater state repression.

A twenty-first-century reader may fairly question the relevance of the views of the IWW today. Despite the IWW’s recent campaigns to organize Starbucks workers and bicycle messengers, it must be admitted that the IWW lacks the social muscle it once possessed. No matter, it remains an alternative vision of unionism that deserves a hearing, and to some, it may even be considered the conscience of the labor movement. The IWW once had a skit where one of the characters pointed at a building and said, “Folks that didn’t build it own it, and the fellows who built it don’t own it, I think that’s crazy” (p. 377). Maybe the IWW has a point.

Back to Joyce L. Kornbluh’s Author Page | Back to Franklin Rosemont’s Author Page