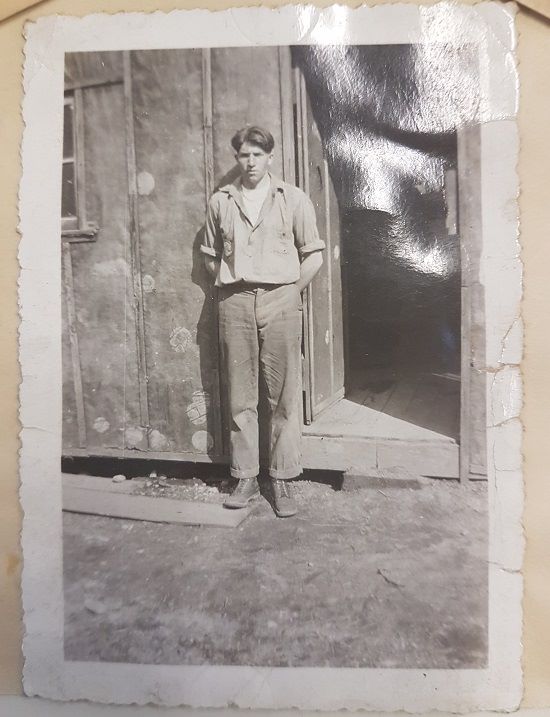

What a black and white photograph of an unidentified man found in the Lakehead University Archives tells us about violent class relations in the twentieth century.

Source: CTKL fonds

This black and white photograph appears, at first glance, to be quite ordinary. An unidentified man poses in front of a tar paper shack, possibly at a logging camp, hands clasped behind his back. His stony gaze is contemplative, confident. Perhaps even defiant.

Although the identity of the individual in this photograph is currently unknown it is almost certain that he lost his life prematurely and tragically, possibly murdered for his beliefs.

The first clue about the identity of this man comes from the fact that this photograph was included in a collage, found tucked inside of an account ledger dating from the 1920s that belonged to the Lumber Workers Industrial Union, headquartered in the Finnish Labor Temple on 314 Bay Street. The creator(s) of the collage, also unknown, believed that he belonged in this collection.

Source: CTKL fonds

The picture of the unidentified man appears to be a one-off, original photograph, possibly local in origin. The other images are mass produced, postcard-sized portrait photos. Together, they tell a grim tale of the fight for workers’ rights in the twentieth century.

Three of the men in the collage – Frank Little, William McKay, and Wesley Everest – lost their lives brutally at the hands of anti-union thugs. The other three – Joe Hill, Nicola Sacco, and Bartolomeo Vanzetti – received the death penalty following famous murder trials that captured international attention amid accusations of unfair trials and racial profiling. With the exception of Sacco and Vanzetti, all of these men belonged to the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW or Wobblies) union.

In Part 2, I will discuss who this man might have been, and who he definitely wasn’t, based on some other clues. This post will concentrate on the other six men included in the collage. Who are these other individuals? Top left: Frank Little (1878-1917)

“Better to go out in a blaze of glory than to give in.”

Frank Little was a leading member of the IWW from its establishment in 1905 up to his death in 1917. A fearless union organizer with Cherokee heritage, the legend of Little – “half white, half Indian, all IWW” – spread throughout the logging, mining, agricultural, oil, and waterfront industries where he fought to improve wages, hours, and working conditions. Little was lynched by vigilantes in Butte, Montana on August 1, 1917.

Little had arrived in Butte, Montana in mid-July 1917, lodging at the Steele Block boarding house located next door to the Butte Finnish Worker’s Hall which housed the offices of the IWW Mine Metal Workers’ Union. Little came to Butte to support a copper miners’ strike against the Anaconda Copper Company, one of the largest and most powerful mining companies in the world. Miners had walked out in protest of unsafe conditions following the Granite Mountain/Speculator Mine disaster, during which an underground fire claimed the lives of 168 miners. It remains the worst hard rock mining disaster in American history.

Speaking at mass meetings of striking miners, Frank Little publicly denounced not only the powerful Anaconda Copper Company, the substandard safety conditions in the mines, poor wages, and the practice of blacklisting pro-union miners, but also the Great War being waged in Europe. Little’s opposition to the war stemmed from his view that it was a “rich man’s war and a poor man’s fight.”

In the early hours of August 1, 1917, Little was forcibly removed from the Steele Block boarding house by six masked men. The men tied Little to the bumper of a car, dragged him along the streets for several miles, and hung him from a railway trestle outside of town. His murderers were never apprehended.

Thousands of miners marched in Frank Little’s funeral procession, many of them Finns. One of them was Reino Erkkilä, then five years old, who marched to the cemetery with his parents behind union banners. These experiences shaped Erkkilä’s understanding of the labour movement and motivated his union activism. He later worked in a variety of roles, including chief dispatcher and president, of the International Longshore and Warehouse Union Local 10 in San Francisco. Top centre: Joe Hill (1879-1915)

“Don’t mourn…organize.”

Joe Hill (born Joel Hägglund) was a Swedish-born IWW

union activist. Hill joined the union while working on the docks in

San Pedro, California around 1910, but worked various jobs around the

country, frequently travelling by freight train. Hill is best known as a

songwriter and is arguably the most famous IWW member. His songs are still sung today on picket lines and labour events around the world, and his story continues to inspire songwriters and artists. Arrested and convicted of murder, Hill was executed

by firing squad on November 19, 1915 in Salt Lake City, Utah.

The incident for which Hill was convicted occurred on January 10, 1914. Two masked men entered a grocery store, shooting and killing a grocer and his son. One of the victims managed to shoot an assailant in the chest before they escaped. Later that same evening, Joe Hill paid a visit to a local doctor seeking treatment for a bullet wound in his left lung. Salt Lake City police used the gunshot wound to tie Hill to the crime.

Hill denied any involvement with the murders. He claimed that he had been shot in an argument over a women by a jealous lover, but refused to name names in order to protect the reputation of the woman in question. In support of his claim that he had hands up when he was shot – unlike the assailant – the bullet hole in Hill’s coat from the exit wound was four inches below the wound on his back. Four other people had been treated for bullet wounds in the city that same night, and police had previously arrested 12 suspects before charging Hill with murder. Hill’s trial and subsequent conviction attracted international attention, including an appeal for clemency from President Woodrow Wilson. Hill’s defenders argued that he had been framed on the murder charge due to his involvement with the IWW.

Joe Hill’s “Last Will” was penned the night before his execution. It reads:

My will is easy to decide

For there is nothing to divide

My kin don’t need to fuss and moan

“Moss does not cling to rolling stone”

My body? Oh, if I could choose

I would to ashes it reduce

And let the merry breezes blow

My dust to where some flowers grow

Perhaps some fading flower then

Would come to life and bloom again.

This is my Last and final Will.

Good Luck to All of you

Joe Hill

Hill kept his sense of humour right up to his execution date. In a note written to William “Big Bill” Haywood, a leading figure in the IWW, Hill wrote:

Goodbye Bill. I die like a true blue rebel. Don’t waste any time in mourning. Organize… Could you arrange to have my body hauled to the state line to be buried? I don’t want to be found dead in Utah.

At his execution, as the deputy in charge of the firing squad called out “Ready, Aim…” Hill, with a smile on his face, exclaimed “Fire — go on and fire”.

In accordance with Hill’s final wishes his body was sent to Chicago and cremated. 600 packets of ashes were then sent to destinations around the world. In 1988, it was discovered that the United States Postal Service had seized one of the packets due to its “subversive potential.” The packet was turned over to the IWW and distributed to various locations as far away as Australia, Nicaragua, and Sweden. A series of letters uncovered recently appear to conclusively prove Joe Hill’s innocence. Top right: William McKay (? – 1923)

“I would rather die fighting the master class than be killed slaving for them.”

William McKay was a logger and member of the IWW in Aberdeen, Washington. McKay was shot and killed on a picket line on May 3, 1923.

In April 1923, the powerful Lumber Workers Industrial Union of the IWW launched a general strike in the state of Washington to force the United States federal government to free remaining “class war prisoners.” Most of these prisoners had been rounded up in massive FBI raids on every IWW office in the United States, culminating in a mass trial of 166 union members in Chicago. The trial has been described as “one of the largest show trials held outside Stalin’s Russia.”

In Washington, 48 logging camps had walked out in support of the general strike. They were joined by groups of sailors and longshoremen in Aberdeen, who picketed the waterfront. In total, approximately 4,000 to 5,000 workers in Grays Harbor County alone joined the strike in April and May 1923.

In an effort to spread the strike, IWW picketers marched to the Bay City mill in Aberdeen, setting up an information picket outside the gates of the mill. William McKay, one of the picketers, took exception to the loud taunting of company gunman E.I. Green who remarked that only “foreigners” and those “who cannot speak English” belonged the IWW. McKay angrily responded “Do you mean that for me?” During the ensuing quarrel Green pulled his revolver and McKay, attempting to flee, was shot in the back of the head and killed. The gunman was later released on bail and never faced trial for the murder of McKay. Middle left and right: Nicola Sacco (1891-1927) and Bartolomeo Vanzetti (1888-1927)

“Never in our full life could we hope to do such work for tolerance, for justice, for man’s understanding of man as now we do by accident.”

Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti were two Italian-born anarchists arrested and convicted of murdering a paymaster of the Slater and Morrill Shoe Company in Braintree, Massachusetts during an armed robbery in 1921. Following a lengthy series appeals both Sacco and Vanzetti, who had maintained their innocence, were executed by electric chair on August 23, 1927.

The trial of Sacco and Vanzetti attracted international attention, including support for their cause in Canada and Thunder Bay. Their defenders argued that anti-immigrant bias and the political beliefs of Sacco and Vanzetti influenced the verdict. Their legal defense argued that this prejudice, along with evidence of coerced witness testimony, demonstrated that the defendants had been denied a fair trial. In November 1925 Celestino Medeiros, a gangster awaiting trial for murder, confessed to the robbery and shooting of the paymaster. Despite the original flawed trial and confession, the Supreme Judicial Court denied a new trial.

In 1977, 50 years after their execution, the governor of Massachusetts issued a proclamation that stated, in part, that “any stigma and disgrace should be forever removed from the names of Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti.” Middle centre: Wesley Everest

“Tell the boys I died for my class.”

Wesley Everest was a logger, IWW union organizer, and a World War I veteran. It is not known when Everest joined the union, but by 1913 he was an active organizer and had previous encounters with vigilantes. Drafted into the United States military in 1917, Everest served in the Spruce Production Division in Washington state which supplied timber for various military needs. He was lynched in Centralia, Washington on November 11, 1919 by a mob in an episode known as the Centralia Massacre.

Centralia lies about 130 kilometres south of Seattle in the middle of Washington’s logging industry. In 1917 the IWW opened a union hall in this strategic location to support the growth of labour union organization in the logging camps. A year after it opened, a mob attacked the hall during a Red Cross parade. Union property was destroyed and members were beaten and driven out of town.

Undeterred, the IWW established a second hall in Centralia in 1919. Rumours quickly spread that the hall would be raided again soon. Local Wobblies sought legal advice from their lawyer who informed them that it if attacked first it would be legal for them to defend themselves.

On November 11, 1919, Armstice Day, the anticipated raid occurred. As a mob forced entry into the hall they were met with gun fire. Four of the mob were killed before overpowering and jailing the union men and destroying the hall. Later that evening, the mob captured Wesley Everest from his jail cell, apparently with no resistance from the police. Everest was then driven outside of town and hung off the Chehalis River bridge. His body was retrieved by the sheriff and deputies the next day and thrown into the cell with the other prisoners with the noose still around his neck. Although no one was ever arrested or charged for the murder of Everest, seven IWW members received prison sentences of 25 to 40 years.