by Jesse Walker

Reason.com

January 29th, 2012

A comic caught between the final gasps of the hippies and the opening blasts of punk.

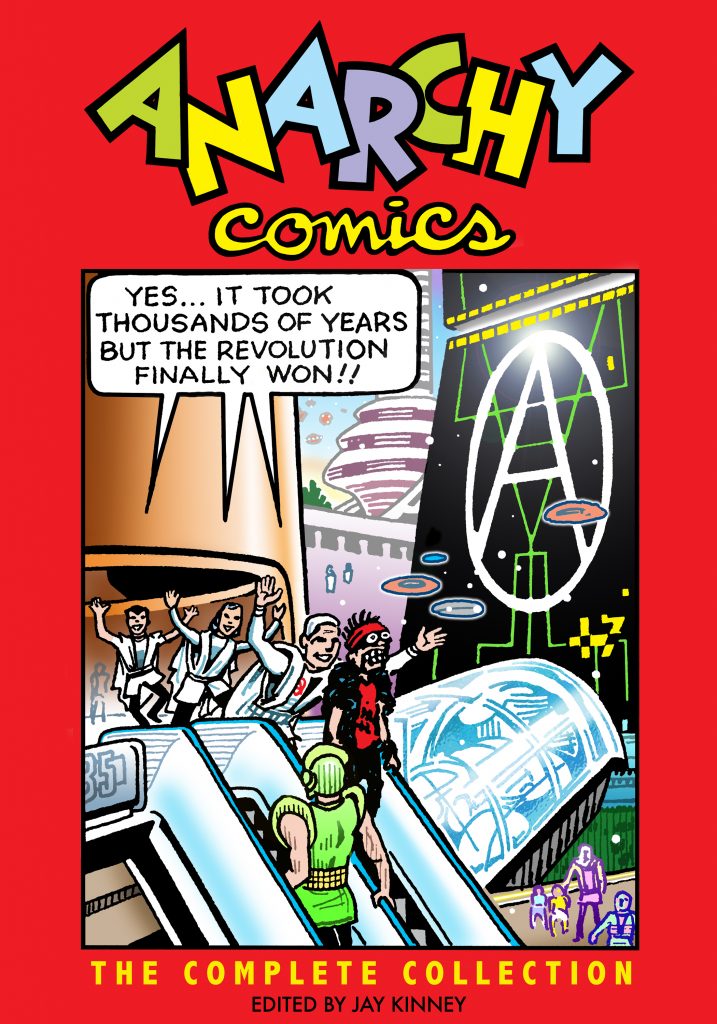

Anarchy Comics had an anarchic publishing schedule, the magazine’s four issues appearing at irregular intervals from 1978 to 1987. The first three editions were compiled by the cartoonist and journalist Jay Kinney, the fourth by his frequent collaborator Paul Mavrides. Several celebrated artists contributed to the comic book over the years, including Clifford Harper, Melinda Gebbie, and Spain Rodriguez, among others. Their efforts hit a wide range of tones, by turns realistic and fantastic, solemn and irreverent.

Now those four issues have been assembled in PM Press’ Anarchy Comics: The Complete Collection, along with various out-takes and ephemera. The strips anthologized here include straightforward stories about anarchist history, cartoons mocking Marxist sectarians, illustrated anti-authoritarian essays, and odd little vignettes that are hard to classify. (The latter include a page by Gilbert Shelton, creator of The Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers, proposing an alternate set of highways he calls “free zones,” where all traffic laws—indeed, all laws of any kind—are suspended.) The left gets spoofed a lot, but it isn’t being spoofed from afar: Just about all the artists and writers come from, or at least have a foot in, the left side of the anarchist spectrum.

Some of the material is basically filler, but there is compelling work here too. Harper, for example, contributes a stark adaptation of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon’s famous definition of government—the one that features the words “To be governed is to be watched, inspected, spied on, regulated, indoctrinated, preached at, controlled, ruled, censored by persons who have neither wisdom nor virtue.”

If that were all that Anarchy Comics had to offer, I might recommend the anthology to friends with an interest in alternative comics or the radical press, but I probably wouldn’t take the time to write a review. But there’s something else here, too: a series of stories by Kinney and Mavrides that are among the funniest satires of the ’70s and ’80s, elevating the anthology from interesting to essential. These strips mock everybody, anarchists emphatically included, in a manner that resembles the comedy of the Firesign Theater, the Illuminatus! trilogy, and the Church of the SubGenius. (With the SubGenii, the similarities are more than just a resemblance. Both Kinney and Mavrides were heavily involved with the mock-church.) As an underground comic that debuted at the late date of 1978, Anarchy Comics was caught between the final gasps of the hippie era and the opening blasts of punk. The Kinney/Mavrides stories captured the moment by firing satiric vollies in both directions.

Kinney and Mavrides didn’t do a strip together in the first issue, but there was a taste of things to come in Kinney’s five-page feature “Too Real,” a collage-comic constructed from clip art and mid-century magazine ads.

It’s a strange, funny, and somewhat free-associative rant that straddles the boundary between earnestness and irony, presented sincerely held ideas in absurd and self-mocking ways. (In one panel, a cat announces: “I am Eleanor Roosevelt with a message from the Vatican! Introduce maximum autonomy into daily life. Stop. Question authority. Stop. Buy food in bulk. Stop. This has been a recording.”) The story had the additional effect of allowing a comic produced by Last Gasp Press, a publisher associated with hippie humor, to lead off with almost half a dozen pages that adopt the aesthetic of a punk-rock flier.

That was a nice setup for the magazine’s first Kinney/Mavrides collaboration. “Kultur Dokuments,” published in the second issue, is really two tales in one. The framing story involves a generic town whose people are rendered as almost-identical pictograms—except for the local LaRouchies and Leninists, who are rendered in the style of the Bizarro World characters in an old Superman comic. The picto people ignore the Bizarros picketing their workplace and instead start their own revolt by “seiz[ing] control of our graphic style,” morphing themselves into individualized drawings that range from Tintin to a talking dog. The metaphor here isn’t hard to decipher.

The Pictos and Bizarros are funny, but they aren’t what makes “Kultur Dokuments” so memorable. In the middle of the strip, drawn in an entirely different style, there’s a sizable story within the story: an Archie Comics parody in which Archie and Jughead are transformed into Anarchie and Ludehead, a couple of obnoxious punks rebelling against the even-more-obnoxious mellow California counterculture.

At one point, the cartoonists reenact the ’60s cliché of a car full of rednecks hurling beer cans at some longhairs. Only this time the beer gets thrown at the punk rock kids, and the people throwing the brew are, well…

For those of you who haven’t been exposed to many underground comics, those three hairy dudes in the car are the Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers, some of the best-known characters to come out of the hippie comic-book world. When I originally read this story in the ’80s, I took their appearance here as a jab at the older feature, but in fact it’s practically a licensed cross-over: Mavrides had just joined the Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers production team.

The hippie/punk split moves to center stage in the third issue, with a Kinney/Mavrides story called “No Exit.” The protagonist of this piece, published in 1981, is a punk singer and self-proclaimed anarchist called J-P who gets murdered by his own fans when they take his lyrics too literally (“Kill the land and kill the sea!/Kill yourselves or kill me!”). He is cryonically preserved, and when he is reanimated 3,000 years later he learns that the anarchist revolution has finally won. But while J-P’s anarchism is nothing more than punk nihilism, the anarchotopia of the future is about as far from punk as you can get, combining New Age fantasies (“I’m getting a telepathic message from the dolphins up on their L5 space colony!”), political correctness (“There’s no more ageism! There’s no more shapeism! There’s no more sizeism!”), and the dreariest direct democracy imaginable:

Not surprisingly, J-P doesn’t fit in well:

The story is merciless towards both J-P, who can barely put a thought together that doesn’t involve smashing things, and the people of the utopian future, a society so cloying it would drive Gandhi to start hurling bricks. By this point, unsurprisingly, Kinney was getting disillusioned with conventional radical politics, moving toward more spiritual concerns (he would soon launch the mystical magazine Gnosis) and absorbing new political influences, not all of them on the left. As he puts it in the introduction to this collection, he grew interested in finding a “new political space beyond the old ‘left vs. right’ dichotomy.” He still thought an anarchist society sounded appealing, but it also seemed like a lost cause—”in part,” he writes, because of all the “revolutionary posturing by its proponents.”

He handed the editor’s reins over to Mavrides, and for the final issue they wrote and drew one more long story together. “Armageddon Outtahere” starred Bud Tuttle, a John Birch–esque character who had earlier appeared in a couple of ’70s comics, Kinney’s Occult Laff Parade and the Kinney/Mavrides collaboration Cover-Up Lowdown. His new adventure featured a gang of anti-food terrorists who launch refrigerators at freeways, a gang of pro-food terrorists who launch cows at freeways, and a gun-toting Jesus who teams up with the Antichrist and Mary Magdalene; it concludes with all the armageddons of the world’s faiths happening at once. It may not be as inspired as the duo’s earlier strips, but it’s still pretty entertaining.

There’s a lot of engaging material in this book’s pages, from a cartoon biography of Victoria Woodhull to a page where Lenin does a Borscht Belt standup routine at an AFL-CIO convention in Disneyworld. But the Kinney/Mavrides stories—especially “Kulture Dokuments” and “No Exit”—are the high points. It’s good finally to have them all between a book’s covers.