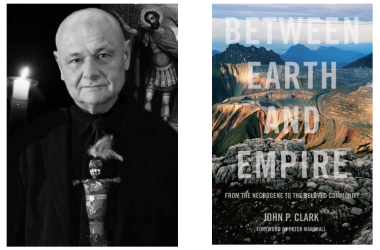

By John P. Clark

Photo: At middle to lower left, Mama D, me, and Merc from the Soul Patrol, with the Family Farm Defenders from Madison, Wisconsin. In the 7th Ward, September 2005.

This is a somewhat expanded version of a text written for a PM Press authors session on “Ideas for Action: Relevant Theory for Radical Change” at the Left Forum on June 3, 2017. In this text I try to summarize briefly, if inadequately, some of the lessons I’ve learned about radical change over the past fifty years. I dedicate it to someone who taught me some of the most important of these lessons, Mama D, the great 7th Ward community leader in New Orleans, who died shortly before this was written, on May 20, 2017.

In the late 1960’s

and early 1970’s I participated in something that was rather vaguely

called “the Movement,” and which was for me above all a comprehensive

movement for grassroots democratic and cooperative projects. During that

time, I gradually learned certain lessons about the possibilities and

limits of grassroots organization from participation in child care

co-ops, food co-ops, alternative schools, the free university, the

worker coop movement, the Industrial Workers of the World, the

anti-nuclear and anti-war movements, various ecological, feminist, and

post-Situationist anarchist groups, and an anarchist affinity group, in

addition to many other experiences. Out of this milieu came a vision of a

new society based on values such as mutual aid and solidarity,

equality, dignity and freedom, peace, love and care. In the new world

that was envisioned, not only production and consumption, but personal

relationships and family life, education and child care, care of the

body and soul, arts, music and recreation, and all other spheres of

existence would be transformed in accord with these values.

Though

the movement of the period did not ultimately fulfill the vision many

of us had of the imminent fundamental transformation of society, it made

many breakthroughs and revealed much about the processes of radical

change. I learned that there exists at certain points in history a

possibility for creating a vast movement in which large numbers of

people quickly become open to change. I learned that there can be a

proliferation of small-scale transformative communities and projects

that become the basis for a large-scale movement for social

transformation. I learned about the power of the radical social

imaginary and the power of a transformative ethos or way of living

everyday life.

In 1974, I visited the Adams-Morgan neighborhood

in Washington, D.C., where I found, in one specific locality at one

particular moment, a convergence of initiatives in community technology,

local self-reliance, neighborhood self-government, community coops, and

communal living, in the context of an emerging liberatory culture with

its own forms of art, music, and communication. From seeing various

degrees of such a convergence, there and in many other places, I learned

that that we can collectively create a new culture and new forms of

organization based on freedom and solidarity.

I also learned

difficult lessons from seeing, by the mid to late 1970’s, the

disappearance or cooptation of most of the constructive social projects

that I had found so inspiring. I learned, on the one hand, that there

are powerful and usually underestimated or ignored obstacles to the

creation of a free, just society, but that, on the other hand, these

obstacles are not material or technical ones. I learned that to sustain

the kind of breakthroughs that we achieved we would have to address more

seriously and, in effect, much more radically, issues concerning the

self and character-structure, human relationships and interactions,

forms of social organization, the nature of ideology and social control,

and (as I learned particularly from the Situationists) the battle for

the imagination.

By the 1980’s I had become heavily involved in a

theoretical and political tendency called social ecology. I learned

more about the history of and possibilities for decentralized direct

democracy and community control of all major aspects of social life. I

learned that we need to have a vision of social transformation that

recognizes the problem of the transition. I developed a deeper

understanding in the rather obvious truth that we cannot merely do good,

and hope for the best, but rather we must consider, carefully and

realistically, what kind of organizational forms could create the new

society and replace the old one. I also learned about the pitfalls of

political sectarianism and the need for openness to many sources of

truth and enlightenment, and, above all, openness to the experience of

communities of people struggling for liberation.

At this time, I

also became active in Central America solidarity movements. From these

movements, I learned about the intimate connection between the

domination around me and the more intensified and brutal forms of

domination elsewhere in the world. I learned that the struggle for

liberation and solidarity must be at once local, regional, and global.

This process of learning continued during the 1990’s, as my political

ideas were transformed deeply by day-to-day involvement in support for

West Papua and East Timor, and especially by engagement in the struggle

against the global mining industry in West Papua. I learned from East

Timor that we should never forget the genocides that are going on at

this very moment, and that it is very easy for the vast majority of us

to do so. I learned from the Papuans about how extractive industry can

transform places with the greatest concentrations of natural wealth into

sites of sickness, death, oppression, poverty and devastation. I

learned, especially from the Papuans, that there are many fundamental

forgotten truths to re-learn from indigenous and traditional

communities. I learned that we have to break with Eurocentric models of

political organization and revolution that had been integral to my own

political formation.

I also became increasingly involved at this

time with the Green Movement. I worked on grassroots issues such local

control and municipalization of utilities, decentralization of political

power, community garden projects, and, above all, the fight against

ecocidal and genocidal transnational corporations and their powerful

influence over local political systems and communities across the globe.

I learned that our local struggles in the semi-periphery are in a great

many ways one with the struggles at the center and in the periphery.

A

crucial turning point at this time was the decision to take the

opportunity to begin buying land on Bayou La Terre in the forest of the

Gulf Coast of Mississippi. I had begun to study bioregionalism and to

think about the process of reinhabitation, or learning to create a

culture and way of life rooted in a sense of place and a knowledge of

the land and the life forms that are part of it. This was the beginning

of over a quarter-century at La Terre, in which I slowly learned about

the power and beauty of the way of nature, and about what Gary Snyder

calls the goodness, wildness, and sacredness of the land. This place,

whose name means both “the Earth,” and “the Land” was to become one of

my greatest educators.

At this time, I also became very active in

the movement against the several strong political campaigns of former

neo-Nazi and Klansman politician David Duke, and, more fundamentally,

against the resurgence of neo-fascism. I learned about the depth and the

insidious nature of long-neglected and long-denied authoritarian and

racist tendencies within contemporary society. I also undertook

extensive study of and writing about the resurgent religious

fundamentalism and the growing power and influence of televangelists and

their media empires. I learned that, in addition to becoming adept at

the use of mass media, the religious right was doing in practice the

kind of grassroots organization that the left, with a few notable

exceptions, has mainly talked about since the Civil Rights, Black Power,

student, anti-war, and community control movements of the 1960’s and

early 1970’s.

In the early 2000’s I began spending time in

India and working with Tibetan refugees fleeing their recent tragic

history of conquest, genocide, and ongoing oppression and colonization. I

learned additional lessons about the power of community and of

traditions of dedicated practice of compassion and non-egocentrism. I

also began studying Buddhist philosophy and its “Three Jewels” more

seriously, and discovered its relationship to radical critique and

revolutionary social transformation. I learned, first, about the

importance of the fully awakened mind, and what some Boddhisattva once

called “the ruthless critique of all things existing.” I learned,

secondly, about the importance of complete dedication to following the

truth along whatever path it takes, and of being completely open to the

lessons of experience of the world and nature. I learned, third, about

the importance of the sangha, or small awakened community of love,

compassion, and care. I learned that the great anarchist geographer

Elisée Reclus also discovered the importance of these “small loving

associations” to the process of social transformation.

I learned

many lessons from direct participation in, or contact with, communities

of this kind. For a number of years, I attended Quaker Meeting and

learned much about consensus decision-making, respect for the person and

the individual conscience, dedication to peace and justice, and the

value of having a long tradition of communal practice to draw upon. I

learned from friends who worked in or were inspired by the Catholic

Worker Movement about the great power of a small community living a life

together based on the everyday practice of peacemaking, pursuing

justice, and expressing love, especially for those greatest need. I also

learned from participation in Zen meditation groups and sanghas about

the deeper meaning of awakened mind, and the challenges of overcoming

egocentrism and the obsessions and distractions of a world of obsessive

consumption and accumulation. I learned that a good criterion for

assessing the value of a group is whether, when one is with its members,

one immediately becomes a better and more joyful person.

Perhaps

the most decisive turning point in the transformation of my perspective

on radical change occurred in 2005, when I experienced the trauma of

Hurricane Katrina, the devastation of much of New Orleans in the

flooding, and the corporate capitalist and structurally racist

re-engineering of the city in the post-Katrina period. I learned the

most important lessons from participation in Post-Katrina grassroots

recovery communities. I learned to appreciate more deeply the meaning

of crisis and collapse. I learned about the role of trauma in personal

and group transformation. I learned that another good criterion for

assessing groups is the extent to which at crucial moments they put

aside everything that is merely habitual and inessential and respond

whole-heartedly to the greatest and most vital needs.

I was

affected powerfully by working with a small recovery community in the

upper 9th Ward of New Orleans. I learned that living and working

together full-time with a small community devoted to serving the most

real and urgent needs of the community is the most fulfilling life

possible. I later learned from working closely with the legendary

community leader Mama D and the 7th Ward Soul Patrol, of the miraculous

powers of a grassroots, matricentric, Rastafarian-influenced

neighborhood group that followed only one principle, “Neighbors Helping

Neighbors.” Contact with many volunteers from the anarchist-inspired

Common Ground Relief, some of whom stayed with me in my home, taught me

about the vast underappreciated reservoir of compassion that exists in

our world, and how engagement in grassroots recovery can bring out the

cooperative and communitarian impulses in people. I learned from Common

Ground about the enormous good that comes from practicing “Solidarity

not Charity” and about the invaluable human quality that my friend scott

crow calls “Emergency Heart.”

I learned above all about the

awe-inspiring power of small communities of care. I learned that such

communities can help people appreciate more deeply what is of greatest

intrinsic value, of what we must, in effect, recognize as being sacred

and beyond all price. At the same time, the experience of disaster,

mourning, and regeneration gave me an increasing sense of urgency about

the need to change the entire present tragic course of world history. I

learned to have a much deeper awareness of and concern about the degree

of suffering and loss that is now taking place, and the vastly greater

level that is to come, should we continue the suicidal and ecocidal

course of capitalist, statist, patriarchal civilization. As the 2010’s

began, all these lessons and feelings were intensified through the

additional trauma of the BP oil spill, with its horrifying spectacle of

devastation, despoliation, and ecocide.

Over much of the past

dozen years, I learned much (as much as from anything else in my life)

from the unanticipated experience of again taking on the challenging

vocation of single parenting, and dealing on a day-to-day basis with

addiction, alcoholism, mental and spiritual sickness, and suffering

within the family and among many others close to family members. I have

learned crucial lessons about the need to reassess priorities as the

result of seeing so many young people lost to a society of nihilism, and

the craving for and obsessive consumption of objects and substances,

ideas and fantasies. I have learned equally important lessons from

seeing others, including those close to me, saved by the power of the

compassionate community. All these experiences and lessons led me to

begin studying non-hierarchical, non-medicalized therapeutic

communities.

I was invited to visit one of the largest and most

studied therapeutic communities in the UK, and had the opportunity to

spend time with people engaged in extraordinary processes of mutual aid

and self-transformation based on unconditional love and complete

acceptance of each unique person. I learned much from seeing the

processes of healing and regeneration at work, there and elsewhere. I

learned that miracles are possible through good practice, through care,

and through openness to possibilities. I learned that—given the ways

that the system of domination generates the voracious, insatiable,

self-destructive ego—the communities of liberation and solidarity that

will be capable of transforming and liberating the world must also be

therapeutic, that is, healing communities.

As a result of all

these slow processes of learning, I decided a few years ago that it was

necessary to leave the university where I taught for decades, and to

start working more directly, full-time, for the process of social and

ecological regeneration. I started a project called La Terre Institute

for Community and Ecology, situated on what has now grown to 87 acres at

Bayou La Terre, in addition to having programs in New Orleans, to help

pursue this work. I have learned from the early stages of the project

that it is urgently necessary to find a small community of similarly

motivated people who can work together, in order to make this

undertaking a success.

I have become preoccupied with the

question of how, given the actual conditions in the world, we can break

with, and then overcome, the capitalist, statist, patriarchal system of

domination, and prevent global collapse, while at the same time creating

a free, just, and caring society. I have learned that it is necessary

to focus carefully on the question: “What is the decisive step?” or

perhaps more accurately, “What is the decisive process?” A few years

ago, in a book called The Impossible Community, a work that was very

much a product of the Post-Katrina experience, I argued for the need to

address at once all the primary spheres of social determination. These

include the social institutional structure, the social ideology, the

social imaginary, and the social ethos. I concluded that to achieve this

goal the most urgent necessity is the creation of small communities of

liberation and solidarity, of awakening and care.

I have learned

from many years of study of social movements that such communities of

this kind can find inspiration in a rich history of micro-communities,

including (to mention just a few examples) anarchist affinity groups,

Latin-American base communities rooted in Liberation Theology, and the

“ashrams” of the Sarvodaya Movement in India, which were really like

prefigurative and transformative ecovillages that were to be created in

every village and neighborhood of India. Further inspiration now comes

from what is being created at this very moment by the Zapatistas in

Chiapas and by the Democratic Autonomy Movement in Rojava.

I

learned that the values and practices of indigenous people in Chiapas

offer much richer and more radical concepts of mutual aid and

solidarity, and much deeper images of communal personhood, than even the

most radical political theory that the dominant society has to offer

us. I learned that the revolutionary movement in Rojava has not only

challenged the centralized state, capitalism, and authoritarian

religion, but has gone further than any other popular social movement in

working to destroy patriarchy and the dominating, appropriating,

hyper-masculinist ego built on it.

I am continually led back to

certain core questions that are implied by everything I have learned and

experienced. What would a movement be like that included each person in

transformative and prefigurative affinity groups and base

communities—that is, in primary communities of liberation and

solidarity, awakening and care? Could such a socially regenerative

movement increasingly move on to create participatory democratic block,

street, neighborhood, town and city assemblies, councils, and

committees? Could such a movement ultimately replace the capitalist,

statist, patriarchal system of domination? Could it create a free, just

and compassionate human community, living in dynamic harmony with the

whole of life on Earth? These questions have only one answer. It is our

lives.