The California Historical Society

By Mat Callahan

June 21st, 2017

Familiarity with a trivial pop tune should not be mistaken for historical knowledge. If we want to understand why any song becomes popular or what it signified when it first was heard, we need to know both the social and political events surrounding its publication as well as what music, in general, was undergoing at the time. In the case of, “If You’re Going To San Francisco”, the song is musically and lyrically unlike what was emerging from San Francisco in 1967. Treacly and maudlin, melodically; stilted and doctrinaire, lyrically, the song was penned by Jon Phillips, produced by Lou Adler and it reeked of its Los Angeles origins from that day to this.

In this context, LA is not a city with its own vibrant culture, but the citadel of power for the entertainment business in the Western World, more particularly, the music industry component of that imperial beast. In fact-as opposed to “myth” or contrived “legend”-young people in SF at the time of the song’s release (May, 1967), especially among musicians such as this author, held the song in utter contempt and viewed its rise up the charts as one more example of the media manipulation of which the “straights” running big record companies were masters. The song bore no resemblance whatsoever to the music made by the Jefferson Airplane, the Grateful Dead, Big Brother and the Holding Company, Country Joe and the Fish or myriad other local bands that were part of the first wave of Sixties SF music. Indeed, the song didn’t even resemble, musically or lyrically, the music of LA’s Byrds or New York’s Lovin’ Spoonful-two groups who had had a real influence on SF’s burgeoning music scene.

Love Is the Song We Sing: San Francisco Nuggets 1965–1970 is the fourth Nuggets box set released by Rhino Records.

Fortunately, for both history and music, we have Alec Palao’s wonderful “Love is the Song We Sing: San Francisco Nuggets 1965-1970”, book and accompanying cds, to provide evidence of what actually occurred. This fine compilation opens and closes with what could legitimately claim to be a theme song of the era, “Get Together” by Dino Valenti. (the definitive version, by the Youngbloods, closes the collection and was in very wide circulation in the Bay Area in 1967). More significantly, it documents the broad range of musical styles characteristic of the time and place-none sounding anything like “If You’re Going to San Francisco.” Just to mention a few: The Sons of Champlin’s “1982-A” is an r&b manifesto as funky and groovy as anything made in Motown or Memphis. Sly and the Family Stone’s first recorded foray, “Underdog”, foretells the brilliant melding of diverse elements by a group that would ultimately epitomize the highest hopes and steepest decline of a generation determined to change the world. And who could mistake the striking contrast between Mother Earth’s soulful evocation of “Revolution” and the syrupy banality of “San Francisco?”

No, the record is clear for those who seek it but this nonetheless has not prevented the music industry, in combination with rock journalism and the Tourist Bureau, from making the song “San Francisco” a “classic” and “iconic” of the Sixties. Along with “Summer of Love” it has been repeated so often that the undiscerning mistake it for historical fact. Misled by these imposters and hucksters, one enters a theme park whose astro-turf Eden overlays a cemetery wherein are buried the bones of dead warriors, the dreams of a better world and the dedicated effort of millions of people to achieve undeniably noble aims. It is not for nothing that these lies and distortions of historical fact are created and perpetuated. It is to ensure that there is never again a movement of such size and strength that it could threaten to topple the tyrants who rule America and much of the world. It is to ensure that the actual people and the work they did are erased from history.

If we seek to explain the larger phenomenon of the Sixties and its ramifications in San Francisco, then we have to understand not only the sequence of events that impelled Phillips and Adler to compose an advertising jingle for their festival-the Monterey Pop Festival-but what made music the motive and the means for so many young people and how, as a result, this made music itself subversive. The phenomenon can be briefly summarized as a synthesis of diversity, unity and liberation; qualities of thought and experience being expressed in the music people listened to several nights a week, for years on end, in venues such as the Fillmore, the Avalon, the Panhandle and the Polo Fields (in Golden Gate Park). On a regular basis, artists such as Rahsaan Roland Kirk shared the stage with the likes of the Grateful Dead. Routinely, musicians like Bola Sete performed alongside Country Joe and the Fish, Herbie Hancock was featured with Taj Mahal and Malo and bills including Dr. John, The Charlatans and Thelonius Monk became the norm, thereby breaking down all the barriers which had been systematically erected by the music industry.

This accounts for a generation learning to love and exalt music, above and beyond all formal categories, as an oracle of truth. This audience in turn inspired a renaissance which was itself a threat to established norms in the United States-business norms, ethical and cultural norms, even legal norms (especially noise ordinances, liquor laws and age-restrictions) which had greatly hampered music’s delivery to people below the legal drinking age and those interested in dancing. What is thereby forgotten is that music was not viewed as entertainment but as an enlightening substance and unifying activity undefiled by commercial exploitation or the ravages of consumerism. Of course, such views were anathema to the system which would ultimately “restore order” including the reversal of every gain, artistic or political, made during the Sixties. This was achieved not only through bribery and cajolery-otherwise known as co-optation-but through brute repression. Artists as diverse as Phil Ochs, Buffy St. Marie, the Last Poets and the Fugs, all suffered government repression, as documented in books such as Eric Nuzum’s “Parental Advisory: Music Censorship in America” and Richie Unterberger’s “Turn!Turn! Turn!”

Anti-Vietnam war demonstrators fill Fulton Street in San Francisco on April 15, 1967. The five-mile march through the city will end with a peace rally at Kezar Stadium. In the background is San Francisco City Hall. (AP Photo)

Similarly, and perhaps of even greater historical significance, were the social movements and organizations that flourished at precisely the same time, in the same place. Musical breakthroughs in the Bay Area were to a large extent made possible by the enthusiastic appreciation of audiences among whom were many people engaged directly or indirectly in opposition to the Vietnam War, support of Black Liberation and advancing the struggle of the United Farmworkers. Not only were thousands of young people mobilized along these battlelines, locally, but organizations such as the Black Panther Party, were gaining international notoriety at the very moment the hype and hoopla surrounding Monterey Pop reached its peak. Indeed, if one considers the widespread attention San Francisco was no doubt receiving from the world’s media (not to mention the rapidly proliferating underground press) there was as much, if not more, attention paid to these political movements and organizations than to their ostensibly hedonistic counterparts in pop culture. The portrayal, therefore, of hippy-dippy, flower children escaping in a drug-induced haze of narcissistic reality-denial, is no more than wishful thinking on the part of the Powers That Be, represented at the time by governor, The image persists, in part, because it’s the image the system wished its opposition consisted of. Of course it did not, and that’s what needs to be examined.

To begin with, the youthful forces of opposition were far more diverse than the image conveys, including black, Chicano, Asian and Native American youth, all of whom were familiar with basic concepts such as the system, the movement, consciousness and liberation. What the Panthers, Farmworkers, Diggers, and other groups could count on was that these terms were the basis for serious discussion and, sometimes, unified action. Certainly, by the time “If You’re Going to San Francisco” was released, these were the concerns of hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of young people and were given powerful expression in marches, demonstrations and occupations, as well as genuinely popular festivals such as the Summer Solstice celebration in Golden Gate Park that followed four days after Monterey Pop. Nor can it be forgotten that only a year before, the Artists Liberation Front had launched a series of Free Fairs, in various San Francisco neighborhoods that were catalysts for community initiative and people’s participation in the arts. The fact that these Free Fairs were punctuated by the police killing of a young black resident of San Francisco’s Hunters Point, Matthew Johnson, sparking a four day riot in the city, followed shortly thereafter by the founding of the Black Panther Party across the Bay in Oakland, gives some idea of the intensity of activity and the social interconnections that were its very fabric. These, in broad strokes, are a small sampling of the quality and quantity of a popular upheaval that was what one song attempted to usurp.

Hunter’s Point residents during confrontation with police violence, September 1966. Photo: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library. Via ShapingSF.

It is above all necessary, therefore, to reject the nostrums of nostalgia, such as “If You’re Going to San Francisco”, in order to more fully appreciate, indeed to enjoy, the many illuminating and inspiring works of the real San Francisco in the Sixties. These works include diverse expressions from murals, posters and comic book art, from street theater to modern dance, from experimental electronic music to latin rock. Much is still available on recordings, in books and on the internet. In order to separate the phony the factual, however, it’s a good idea to maintain a finely-tuned bullshit detector.

_______________________________________________________

About the author

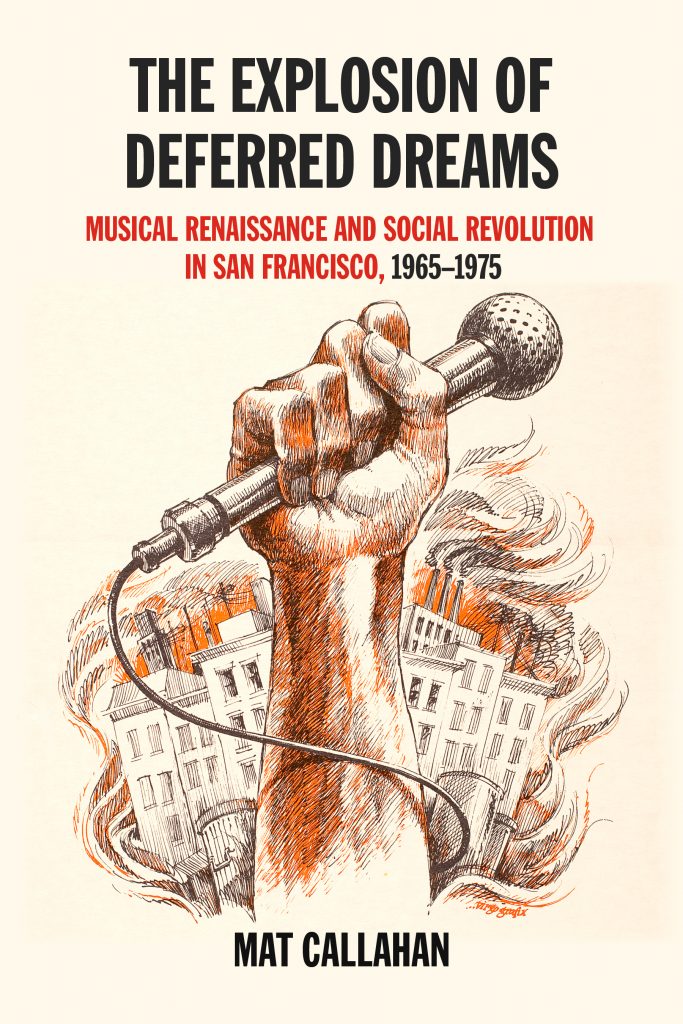

Mat Callahan is a musician and author originally from San Francisco, where he founded Komotion International. He is the author of three books, Sex, Death & the Angry Young Man, Testimony, and The Trouble with Music as well as the editor of Songs of Freedom: The James Connolly Songbook. His most recent book is The Explosion of Deferred Dreams: Musical Renaissance and Social Revolution in San Francisco, 1965–1975. He currently resides in Bern, Switzerland.