by Vittorio Frigerio

Anarchist Studies 24.2

December 2016

There is more than a whiff of melancholy that comes off the pages of PM Press’s reprint of the complete run of the magazine Anarchy Comics (four issues in all, from 1978 to 1987). The age of the 1960s counterculture, that spawned such phenomena as the wave of underground comics that brought a much-needed breath of fresh air to a field stifled by Comics Code Authority-censored superhero fare, seems now as distant as the Middle Ages. And although this magazine came at the end of that period, it is still fully a product of those times. But Paul Buhle is right, in his introduction, to affirm that this work has ‘lost nothing of its power for today’s troubled world’ (p 8). The question to be asked, then, is why.

Jay Kinney, the originator of the project and its main contributor, together with Paul Mavrides – better known for his work on one of the era’s most iconic productions, the Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers – provides a fairly lengthy introduction in which he retraces the history of the publication, giving much infor- mation about the making of the various issues, and his artistic as well as ideological intentions. Kinney states that his basic idea was ‘to do an underground comic incorporating both lefty-anarcho politics and punk energy’, but one that would not be ‘a strictly doctrinaire exercise in propaganda’ (pp 10-11).

Another important element of the project was to incorporate an array of different voices from various countries, as each issue blared on its front page: ‘International Anarchy!’, listing the origins of the contributors: American, Canadian, French, Dutch, English and German cartoonists. But the finished product looks and reads like pure California. Amongst the contributors, some are particularly worthy of notice, such as well- known German artist Gerhard Seyfried, whose emblematic representation of a black-clad, hatted and grinning anarchist holding an old-fashioned bomb has almost become the equivalent of a logo for the movement.

Anarchy Comics also presented some (at first rather summarily) translated works by French authors Frémion and Volny, who were central in the evolution of the bande dessinée during that time, through the magazines L’Écho des savanes and Fluide glacial. Most of the work, and frankly most of the best work published in Anarchy Comics, was signed by Kinney and Mavrides themselves. While the length of the various comics is very different, ranging from single strips to stories spanning several pages, some tendencies do jump out. One is to present little-known but significant moments in the history of the anarchist movement and its heroic protagonists.

Thus we get: the history of Nestor Makhno, Durruti and the Commune of Paris by Spain Rodriguez; the revolt of Kronstadt, and that of the Alsatian ‘rustauds’ by Frémion and Volny; the history of the Wobblies by Steve Stiles; a portrait of Benjamin Péret as a militant by Melinda Gebbie and Adam Cornford. These are the more overtly pedagogic of the comics included in the four issues of the magazine.

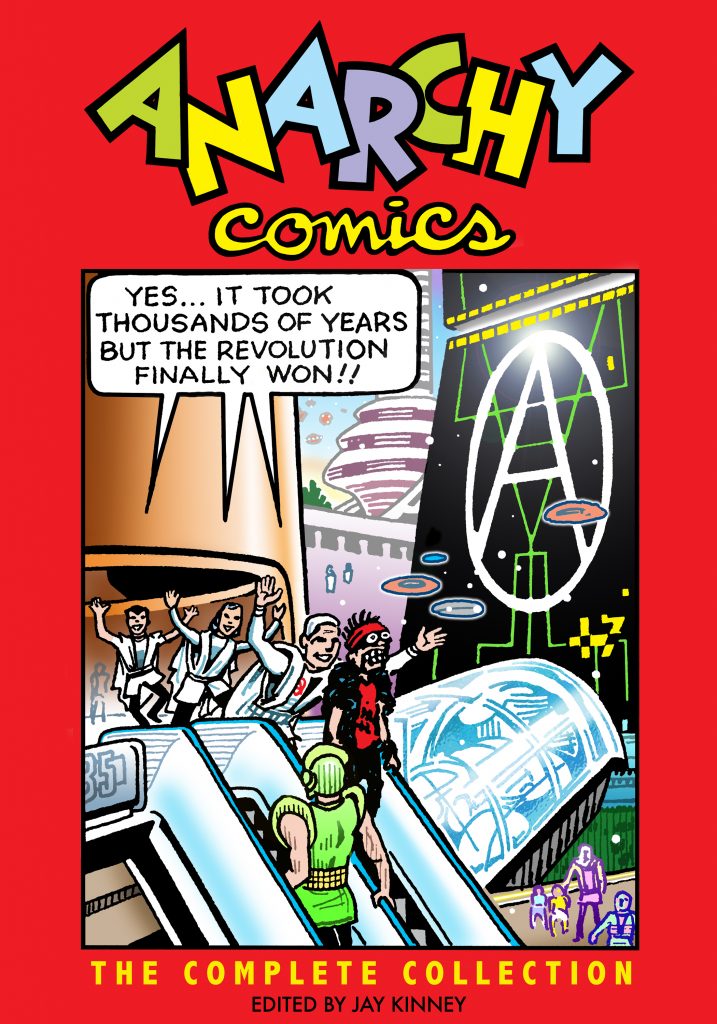

In their attempt at providing a maximum of information and instruction in a minimum of space, it is striking to see the extent to which they reproduce the narrative topoi found in similar types of productions in conservative comic publi- cations elsewhere – such as the famous series ‘Histoires de l’oncle Paul’ in the Catholic-oriented magazine Spirou in Belgium, featuring the lives of saints and generals. Another typical narrative ploy is that of taking stock situations, such as the father-daughter generational tensions used by Cornford and Kinney to tell the story of the ‘Autonomia’ group within Italian universities in the 1970s (‘Roman Spring’). Or again, the group of friends facing different destinies through which the reader discovers the story of the Commune. When history is put aside, however, so is recourse to traditional methods of story-telling. If, as Bohne contends, these stories still deserve to be read today, it is because of their healthy disregard for seriousness, their ability to hijack just about anything, including Archie comics (that becomes, of course, ‘Anarchie’), and to make fun, not just of the capitalist oppressors, but also of the self-righteous revolutionaries who think they have all the answers. Reading these stories is like being on a rollercoaster, going from laughter, to indignation, to curiosity, and also to admiration for the sometimes very effec- tive and striking graphic solutions offered by the artists. The first story of issue number one, entitled ‘Too real’, is a five-page collage of advertising clip art from old 1950s magazines by Kinney that is still resolutely modern. The story ‘No exit’, by Mavrides and Kinney, featuring a punk finding himself transported into a far- future society where anarchist revolution has been achieved – and finding himself just as out of place there as anywhere else – is both a combination of astonishing graphic talent and a very funny take on the old Rip Van Winkle plot. Anarchy Comics may not be the first book to give to somebody who wants to learn what the movement is about, but it sure is a good way to find out what anarchism can inspire even in the most unexpected fields.