A Dispatch from the Frontline Trenches of Higher Education in Middle America

By Walt Howard

American Communist History Journal

January 2011

Carl Mirra, The Admirable Radical: Staughton Lynd and Cold War Dissent, 1945-1970 (Kent State: Kent State University Press, 2010).

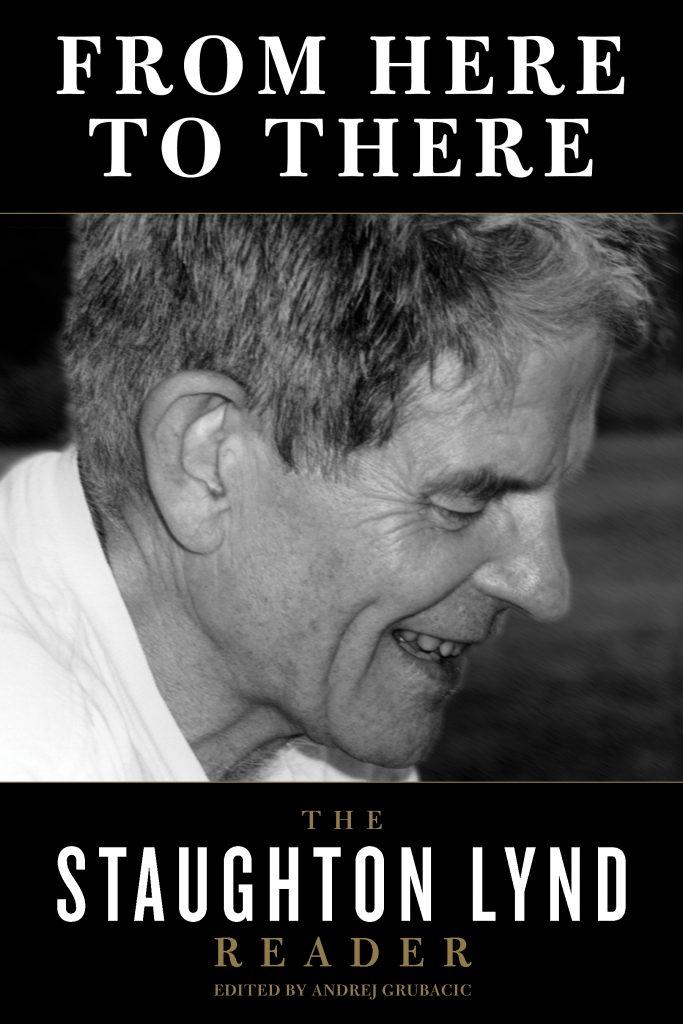

Andrej Grubačić ed., From Here to There: The Staughton Lynd Reader (Oakland, California: PM Press, 2010).

Introduction

Carl Mirra’s The Admirable Radical and Andrej Grubačić’s From Here to There, two valuable tomes, employ the powerful tools of radical history and radical political theory to deal with crucial political, social and moral issues of post-industrial and post-modern American imperial society and culture. They also confirm the iconoclastic historian-activist Staughton Lynd as a contemporary saint and prophet of the American social democratic Left. I do not believe that it is hyperbole to state that Professor Lynd is the American E.P. Thompson and the American Ignazio Silone. Concerning the latter Marxist thinker, Lynd embodies the conception of “accompaniment”: he dwells with, and focuses on meeting the tangible needs of, the American working class in the “rust belt” near Youngstown, Ohio. In Ebonics, one would say he not just “talks the talk, but walks the walk.”

A Proud Son of Appalachia Meets Staughton Lynd

A graduate student in American history at Florida State University (FSU) toward the end of the 1970s, I warmly recollect bonding with my advisor, Neil Betten, the specialist in Labor and Urban History, by way of our mutual admiration for the inspirational Staughton Lynd. Neil is the son of union activists, and I am a proud son of Appalachia and the descendent of peace-loving coal miners. At one of our first meetings, I smiled with an earnest heart as Betten and I both realized that we shared Lynd’s social democratic principles and both believed in the sincerity and influence of his life and work. In due course, Professor Betten launched me as a new Ph.D. into the academic realm to spread the Lynd gospel of non-violent radical change based on participatory democracy.

In the many years since then, as I have explored the life and accomplishments of Staughton Lynd, I have had the good fortune to exchange emails with the likes of Yale’s Edmund Morgan and even take an urgent phone call from the enigmatic Eugene Genovese. This is heady stuff for a “grunt historian” such as myself who labors mightily at a small state teaching university in old Molly Maguire territory in northeastern Pennsylvania. Nonetheless, this is the special attention one garners by researching the life and career of a New Left icon. Both of these eminent scholars, Morgan and Genovese, offered fascinating comments and analyses of Lynd. Morgan suggested that if Staughton had stayed at Yale after his December 1965 trip to Hanoi he would have indeed been recommended for tenure by the Yale history department, and perhaps not put on waivers. In his book, Mirra convincingly reveals this claim to be highly questionable. Furthermore, an excited Genovese told me that he now admires his former rival on the Left, bares him no ill will, and that in the long run, Lynd’s 1969 efforts to politicize the American Historical Association foreshadowed the coming politicization of all the professional associations in the various disciplines of the Liberal Arts. He now seems to recognize Staughton as a prophet.

Astonished and thrilled by this responsiveness from two such eminent scholars, I freely confess that I represent the historical profession at a level often overlooked or minimized by my more prominent and renowned senior colleagues. A descendent of Eastern Kentucky coal miners and United Mine Workers [UMW] activists, an Appalachian “Norman Pollack populist” by temperament, and a humble graduate of FSU’s Ph.D. program in history, I found myself professionally drawn to Lynd more than Genovese or even Christopher Lasch, both of whom I have great respect for. Moreover, like historian Herbert Gutman, by the late 1970s, I already considered the Consensus School of historiography hopelessly outdated.

A young aspiring historian of that day, I was excited by the possibilities of history “from the bottom up,” and encouraging the growth of a social conscience among my students. As a Lynd enthusiast, over the decades since those conversations with my FSU advisor in the Seventies, I have taught innumerable U.S. history survey classes and many upper division courses in Labor, Social, and African American history, to hundreds, perhaps several thousand, of ordinary college students from Middle America at five different institutions of higher learning from Florida to Pennsylvania. I have even taught history to federal inmates in the prisons of Lewisburg and Allenwood, Pennsylvania until Bill Clinton and the Democratic Congress ended Pell Grants for federal inmates in 1994. After over thirty years in the trenches of American college classrooms, my countless Lynd-oriented courses are a fait accompli. Things cannot be changed. In this regard, to a considerable extent, Omar Khayyám’s “moving finger” trumps the lunacy and dribble of David Horowitz, Lynne Cheney, and all the representatives of the New Right and conservative talk radio, at least in the case of my academic career at the grassroots level of higher education.

My coal mining grandfather, and name-sake, who had little formal education, and who was as much my mentor as Lynd and Betten, taught me important lessons as to a thinking man’s moral and social responsibilities in a democratic society. This mentor from my working class family, a UMW and CIO organizer from the 1930s, undoubtedly grins from his grave as I try my best to fulfill this responsibility through human rights scholarship that gives voice to powerless, marginalized groups. I would email country music bard Merle Travis (“Sixteen Tons”) about this state of affairs if he still walked the earth; it would make a great coal miner folk song. Interestingly enough, near the end of his life in the mid-1960s, my miner grandfather told me that he wished someone would go to North Vietnam and talk to its leaders and tell them that some of the working class coal miners in America, who were not Communists, wanted to use common sense and settle the Vietnam conflict without prolonged violent conflict. This conversation took place in the “holler” known as “Bailey Branch” near Wooton, in Appalachian Kentucky, in 1965.

I was overcome with a feeling of serendipity when Lynd once informed me that during my grandfather’s lifetime, he hitched-hiked through Kentucky coal country and witnessed up close the poverty and deprivation of its hard-working people. In 2010, in my current scholarly endeavors, he and my grandfather cross paths again. There is more: in the Freedom Summer of 1964, when Lynd was at Miami University in Oxford, Ohio, at the time of the tragic Klan assassination of civil rights workers Schwerner, Chaney, and Goodman, I was a hillbilly child and Appalachian-in-exile student in the public school system of Hamilton, Ohio, a landing place of many Appalachian coal mining migrant families, just twenty minutes away from Professor Lynd.

With this industrial Appalachian background, I have looked forward to reading The Admirable Radical and From Here to There. Having met Lynd several times over the years as a professional historian, I have enormous respect for him. In my long, unlikely and modest intellectual journey from Wooton, Kentucky to Bloomsburg University in Pennsylvania, Lynd has been a key figure in shaping my professional identity. My trek as a working class teacher-scholar from the “hollers” of Eastern Kentucky to the halls of academia drew direction and inspiration from this particular New Left lion.

It is also from such an authentic working class American perspective that I examine this important scholar who descends from academic royalty. All told, Lynd’s work includes his unique contributions to historical analysis such as the enduring classic, Intellectual Origins of American Radicalism, first published in 1968, and his other work as a talented colonialist regarding the American Revolution. The rumor is that Ed Morgan, who helped recruit Lynd for Yale, considered him the most gifted colonialist of his generation. Apologies to Bernard Bailyn and Gordon Wood.

One must also recognize that Lynd’s oeuvre also includes books on the politics of the Sixties such as The Other Side in 1967 and The Resistance in 1971. Finally, he has penned several works on the American labor movement such as American Labor Radicalism (1973); Rank and File (1981); The Fight Against Shutdowns—The Youngstown Steel Mill Closings (1982); Empty Promise—Quality of Live Programs and the Labor Movement (1987); and Solidarity Unionism: Rebuilding the Labor Movement from Below (1994).

Mirra’s book is, in my estimation, just the first biography of Lynd; there will doubtless be several others in the coming decades as more historians focus on the watershed decade of the 1960s. The Admirable Radical was penned by a first-rate scholar, a Marine Corp. veteran, and antiwar activist in the ranks of “Historians Against the War.” Carl Mirra, associate professor at the Ruth S. Ammon School of Education, Adelphi University, Long Island, New York, is a proven historian, and the author of Soldier and Citizens: An Oral History of Operation Iraqi Freedom from the Battlefield to the Pentagon. He is just the kind of historian-activist one might expect to be a Lynd scholar. His biography is a well-researched and well-written exceptional study that explores Staughton Lynd’s life and career during the Cold War era of American history to 1970. And yes, there is another scholar-activist, Mark Weber, from Kent State University, who is working on Lynd’s life and work since the Seventies.

In any case, future biographers and discerning, serious readers of Mirra’s and Grubačić’s books might take a cue from UC–Berkley’s Hubert Dreyfus (dean of America’s Martin Heidegger scholars), and acknowledge an existential quality to the life and work of Lynd that transcends the categories of the Left-Right divide and even the Culture Wars. Like a Heideggerian existential “Dasein,” more than a fully self-conscious Sartrean Marxist figure, or Camus’s fatalistic “Sisyphus,” Lynd has absorbed, articulated, and above all, embodied, a distinctive way of “being” a uniquely American radical in the second half of the 20th century (and the early 21st century).

If truth be told, I say with certainty, Lynd’s life and example as

presented by Mirra and Grubačić would resonate with some rebellious,

restless and discontented Eastern Kentucky coal miners and their sons

and grandsons, as well as a few FSU history Ph.D.s. More than a few coal

miners from Appalachia, and their descendants, would appreciate Lynd’s

defiance of Cold War authority and his distaste for the limited

effectiveness of “corporate liberalism.” Like the Appalachian miners,

Lynd is fearless in his moral and political convictions. A careful

observer can detect Lynd’s authentic radicalism not only in his actions

but also in his demeanor and carriage; indeed, in the very distinct way

he walks and talks. There is an existential (Heideggerian) maxim of poet

William Butler Yeats that “Man can embody truth, but he cannot know

it.” I have myself witnessed this phenomenon in regard to Lynd several

times at various conferences and basement meetings. In 2010, as an

over-worked history professor, I try to convey a Lynd-like

“Weltanschauung” and hopeful social democratic vision of the future to

about 150 college students every semester. Indeed, I have done so for

over thirty years.

New Left History: A 21st Century Work-in-Progress

Some scholars of the American Left classify the extraordinary Staughton Lynd as one of the historians who epitomizes the finest qualities of the New Left in the second half of the twentieth century, and early 21st century. Though, as a biographer, Mirra advances a complex and nuanced handling of Van Gosse’s relevant “declension” theory in analyzing Lynd and the New Left, it is nonetheless true that New Left legend Lynd has remained true to the early Sixties ideas of non-violent radical change built out of meaningful, grassroots participatory democracy. Lynd himself sometimes contrasts his political orientation and convictions with those of his celebrated father and mother, Robert and Helen Lynd, best known for writing the groundbreaking “Middletown” studies of Muncie, Indiana: Middletown: A Study in Contemporary American Culture (1929) and Middletown in Transition (1937), two enduring classics of American sociology. Robert Lynd was “Old Left” and his son, whom he had such grand ambitions for, Staughton Lynd, was “New Left.”

Inspired by Lynd’s special libertarian version of New Left activism and thought, Andrej Grubačić’s reader is, in effect, really an inspiring anarchistic primer on how an historian can be an agent of radical change in partnership with grassroots radical democracy that empowers the poor as well as despised and oppressed groups. To fully understand and appreciate Lynd’s anarchism from the bottom up, and his social democratic ideas, we need context.

As a matter of history, the New Left came out of the termination of Soviet control over the international Marxist-Leninist movement after the astonishing happenings of 1956. Needless to say, these specific events included Nikita Khrushchev’s well-known speech denouncing Stalin and his many crimes in addition to the East European revolt of Hungary (and before that Poland) as well as the Soviet reaction. What is more, the resolute opposition made by Maoist and Trotskyist parties around the globe to Soviet ideological management must be considered in any analysis. Later, the Cuban Revolution (1959), the fierce anti-colonial struggles in the Third World, and the Che Guevara legend, suggested to those who clamored for radical change that there were diverse approaches to fundamental political and social transformation, and that other social groups, separate from the modern working class, may well be the instrument of revolutionary change. Undeniably, in Staughton Lynd’s non-violent, democratic political universe, it was indeed students, women, racial and ethnic groups, as well as the anti-Vietnam War activists in Europe and the United States, who organized and stood up to challenge the status quo.

Beginning in the Fifties, reaching a highpoint in the Sixties, and even spreading into the Seventies, an assortment of vital social, cultural and political movements struggled to make radical democracy and measurable equality realities in America. A revolutionary notion of democracy enlivened the movements for civil rights and black power, for peace and unity with the Third World, and for gender and sexual equality. Mirra and Grubačić, I believe, interpret the New Left as the broadest-based movement for fundamental change in American history. Like Lynd, they still see the New Left as a work-in-progress in this century in regard to the peace movement, feminism, green parties, and resurgence in thought and action on the Left.

It was American sociologist C. Wright Mills who introduced the term “New Left.” He did so in a theoretical document in 1960 titled Letter to the New Left. In it he called for a new “leftist” creed to replace the “Old Left” and its emphasis on industrial labor. This new radical paradigm opened up the space for Staughton Lynd and other New Left thinkers and activists. Lynd and other like-minded radicals did not seek to recruit industrial workers, but instead focused on a social activist approach to organization of powerless, marginalized groups.

Staughton Lynd represents the elements of the New Left that were essentially “anarchist” in their orientation. He and others like him looked to libertarian socialist traditions of American radicalism as well as the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) and shop-floor union militancy. Lynd’s brand of New Left activism was also inspired by African American activists such as Bob Moses and the Student Non-violent Coordinating Committee. Lynd’s New Left students and organizers, moreover, immersed themselves in poor communities building up grassroots support based on community organizing. Staughton Lynd’s New Left sought to be a broad based, grass roots movement.

Grubačić’s anthology deals with Lynd’s brand of anarchism. Perhaps many American readers will not be familiar with this radical political theorist. Andrej Grubačić, an anarchist theorist, sociologist and activist, has a Serbian background and also advocates an anarchist approach to writing history from “the bottom up.” He is one of the protagonists of “new anarchism,” and a member of the anti-authoritarian, direct-action wing of the global social justice movement. An associate with Peoples’ Global Action and other Zapatista-influenced direct action movements, Grubačić’s primary concerns are political struggles in the Balkans. Like Staughton Lynd, his political thought and interests focus in large part on defining his brand of anarchism as participatory democracy and decentralized power based in local communities, not highly centralized political parties and not highly centralized leftist movements. Grubačić’s attraction for anarchism arose out of his experiences with the Belgrade Libertarian Group that derives from the Yugoslav Praxis experiment.

Staughton Lynd or Christopher Lasch?

I want to avoid the alluring temptation of participating in the Staughton Lynd versus Christopher Lasch debate. I leave that task to the exchanges between two able advocates: Carl Mirra and John Summers. Instead, let me acknowledge that in Lynd’s defense he has recently countered the old, tired charge of presentism and stated that “I believe that historians should look to one another’s scholarly products and evaluate these by conventional academic methods.” Furthermore, another scholar has asserted that “Partisanship is what historians, and scholars in other liberal disciplines, are bound to display as a simple feature of their individual character. The approach made to documents is bound to be different for the religious or the secular, the radical or the conservative. Some of the most intellectually and morally instructive history has been written by passionately partisan scholars.”

In light of these insights, it is arguably the case that Staughton Lynd is one of Clio’s best scholar-activists, and in academic circles, even now in the early 21st century, he calls to mind the turbulent 1960s, the contentious New Left, and a divided historical profession. To be sure, for decades, a number of Clio’s devotees have loved and admired him; others, not so much. Professor Lynd spoke in 2007 before a large audience of hundreds of students and faculty at my academic home (Bloomsburg University of Pennsylvania) in opposition to the Iraqi War. But the interesting thing is that not only local militaristic “Patriots” (now leaders of the local Tea Party cadre) showed up to attack him, but even a few of my fellow Americanists, for whatever reason, in the history department refused to recommend to their students that they attend this talk. One particular colleague who objected to students attending Lynd’s talk echoed Staughton’s story of how C. Vann Woodward at Yale once told him in the 1960s that there were too many “commies” in SNCC (the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee). Regardless, we need more historians of New Left figures and the 1960s movements such as Van Gosse of Franklin and Marshall, biographers such as Carl Mirra, and radical theorists such as Andrej Grubačić.

Present-day historians correctly point to Lynd, as well as the late Howard Zinn along with Jesse Lemisch, as instigating and cultivating an innovative style of American historiography that investigates ordinary people in addition to the privileged, or “history from the bottom up.” History has, of course, traditionally been taught by articulating the important political events of the past and by admiring prominent people. Owing to Lynd and others like him, however, during the last four decades historians have expanded the range of their query into the past. Consequently, we are able to talk about and comprehend the historical process in a much more all-encompassing fashion. Thanks in large measure to Lynd, Zinn, and Lemisch, among others, “history” is now understood to take account of the narratives of everybody: the celebrated and the everyday, the learned and the uneducated, women, men, and children, the wealthy and poverty-stricken, and people of all races and ethnic groups – together all of these people create the full tapestry of American history.

In any case, nowadays, there may be a Staughton Lynd revival taking place in at least one area of American intellectual life: academic history. Indeed, accolades abound for this renowned historian-activist: “The Admirable Radical” pronounces biographer Carl Mirra; “Legendary Historian, Attorney & Peace Activist,” states another source; “Forever Young: Staughton Lynd at 80,” proclaims Andy Piascik in a Center for Labor Renewal publication; “The Marching Saint,” decrees historian Paul Buhle; “The Return of Staughton Lynd,” declares David Waldstreicher in his praise of the recent reprint of the Intellectual Origins of American Radicalism.

According to Mirra, Lynd is an historian with a place in history. After all, in 1964 he did successfully direct the Freedom Schools in Mississippi during Freedom Summer. Without a doubt, however, he will be most remembered for his 1965 trip to Hanoi (North Vietnam) in the company of a young SDS (Students for a Democratic Society) radical Tom Hayden and Communist historian Herbert Aptheker. Now in his eighties and as active as ever, this seemingly ageless Sixties stalwart has moved on from this particular controversy to earn all the tributes noted above. He has merited them through his continuing radical political commitments and boundless energy. In fact, as an independent scholar, Staughton, often in partnership with his accomplished wife Alice (also an attorney and fearless activist), works harder than most full-time academics I know.

Further, the key to understanding the many sides of the protean Staughton Lynd is to recognize his unswerving Heideggerian existential authenticity. In their respective books, both Carl Mirra and Andrej Grubačić implicitly make the case that Lynd stands out as one of the most important, relevant intellectual-activists in post-World War II America. In the historical profession itself one need only to look at the work of the current generation of colonialists, represented by Duke-trained Woody Holton, William and Mary’s Jennifer Oast, Yale-trained David Waldstreicher and many others.

In today’s political universe, public intellectuals such as Howard Zinn, Noam Chomsky, Sean Wilentz, Tony Judt, and Victor Davis Hanson, among many others, are not unusual. Nonetheless, room must be made for the original, ageless Staughton Lynd, if for no other reason than the depth of his radical thought and the genuineness of his sterling character. In old age, as two truly long distance runners from the Sixties, Staughton and his wife Alice continue to actualize the Herbert Marcuse idea of living in a state of revolutionary ecstasy.

Conclusion

The Admirable Radical stands as a significant contribution to the scholarly literature of social history of post-WWII America, and no doubt will be of interest to cultural and intellectual historians. Contrary to some claims, Mirra has not written a hagiography. But of course he is a great admirer of Lynd. All the same, the author seeks to place this public intellectual/historian inside a particular American radical tradition. In the process, Mirra stresses that he does not ask for “a cult of personality” in regard to Lynd. To be sure, he endeavors to plot a successful course between his fondness for his subject and academic impartiality. In this I believe he succeeds. The radicalism of Lynd, according to Mirra, has been, and continues to be, guided by a key Jeffersonian ideal; namely, the right of revolution on behalf of the oppressed. In spite of the historical examples of all the late 1960s militants with their “over the top” revolutionary rhetoric, Lynd still has full confidence in social change achieved by nonviolence and “participatory democracy.”

Bloomsburg University of Pennsylvania