The Oberlin Review

March 14th, 2014

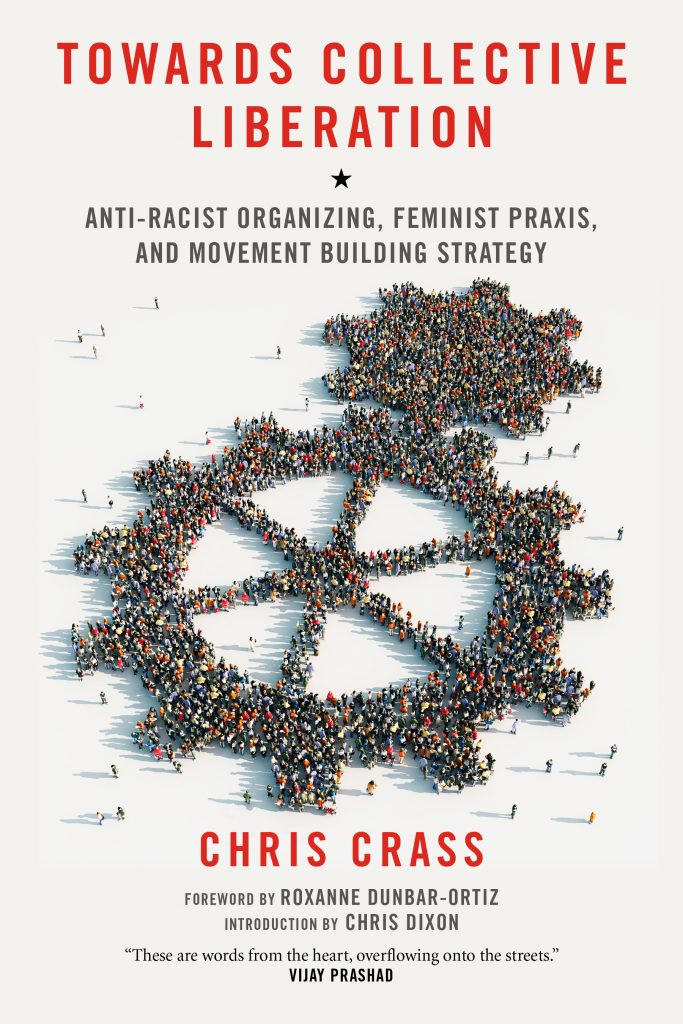

Author, educator and organizer Chris Crass is often at the forefront of multiracial and feminist movements. Crass sat down with the Review this week to talk about his experience as an activist and his thoughts on antiracist organizing.

The topic of your talk, “Anti-Racist Organizing in White Communities,” is something that our college has been struggling with, both as an institution and as a student body. Could you begin by talking about the difference between racist and anti-racist organizing?

It’s a really common

experience for white people who are socially conscious and who are

coming to awareness about issues of race, particularly with the campus

having the Day of Solidarity. There’s going to be a lot of folks — white

folks in particular — being like, ‘Oh my God, I haven’t thought about

this before,’ or, ‘I didn’t think it was this bad,’ or, ‘I thought this

was something that was in the past,’ or ‘I don’t want to be part of the

problem,’ and then one of the first next steps [ for those groups] is

often the question of how to diversify. I’ve had a lot of experience

being a part of mostly or all-white social justice progressive efforts

where [that drive to diversify often comes first]. But the question

that’s often more helpful is, ‘How can we be a part of challenging

racism? How can we be a part of ending institutional white supremacy?

What are positive steps, as a white environmental group, we could take

to support environmental justice efforts by students of color?’ One of

the ways that white supremacy really impacts white people is to

invisible-ize the work that’s happening in communities of color, the

leadership that’s happening in communities of color, the voices, the

perspectives — sometimes you’ll have white activists come to

consciousness about race and be like, ‘Oh my gosh, we have to get people

of color to join our group,’ and then there’ll be activists of color

who will be like, ‘Well, we’ve been working on these issues for a really

long time, so rather than coming to us and asking us to diversify your

group, it’s more of how could you, as a mostly white group, support the

work that students of color are already involved in and build

partnership and trust.’

What are some positive steps that Oberlin can take toward anti-racist organizing?

Some

key ones are learning about work that’s already happen[ed] historically

in communities of color, learning about issues. So if you’re in a

social justice or progressive student group that’s mostly white, what

are issues that students of color are working on, and what are some ways

that your group can help support that work? A way that racism often

operates is [by determining] whose voices are prioritized. Who’s been

told all of their life, ‘You have an important story to tell. You should

tell the world about what you think.’ And then there’s a lot of folks —

women, queer folks, trans* folks, working class, folks of color — who

are regularly told, ‘You have nothing useful to contribute. These aren’t

spaces that you even belong in, let alone that you should be working

in.’ [It’s about] working to recognize those kind of barriers and having

open conversations with activists, leaders of color on campus about the

struggles that [you’re] facing and how to think about it together. It’s

not going to folks of color and [asking them] to solve all the problems

but having genuine conversations about how to overcome these obstacles.

How

would you explain the reality of institutional racism to someone who

might not be familiar with its historical and cultural background?

No

one was born with it all figured out. First of all, the way that racism

operates is that it socializes and rewards white people to be

completely ignorant of racism. The fact that there are so many white

people who feel attacked, or who think that it’s racist to even talk

about racism, is evidence of how powerful racism operates. Because in

communities of color, historically and today, the impacts of racism are

so stark. Often white people today look back at white people in the past

— whether it’s the white people who were participating, supporting,

oblivious [to] or on the sidelines of slavery, or white people who were

supportive or on the sidelines of Jim Crow and apartheid in the sixties —

and say, ‘How could they have just done nothing?’ [They think] it’s so

obvious. People 30 years from now will look back on us today and say,

‘How could white people have not been aware of the mass incarceration,

of the mass poverty, of the incredible disparities and not done

something?’ As students, [we need to] recognize that we are historical

actors, and just as we look on the past and think it was so clear,

people will look back on our day and think that it’s so clear. Because

in the past, people often said that it was too confusing, that there was

no issue, that it was cultural. [We have to] recognize that we need to

make a choice [about] what side of history we want to stand on. It can

be a hard journey, but it’s one that ultimately connects us back to our

deepest humanity. [We need to get] away from fear, away from ignorance,

away from hate and toward a deeper love for ourselves and the people in

our community. [People say,] ‘Well, the reason there’s so many black and

brown people in prison is because of these reasons,’ and there’s all

this justification in the way that the media portrays it, and throughout

history that’s always been true. It wasn’t just this super clear cut

obvious right and obvious wrong. So we need to take responsibility to

investigate and learn and also to open ourselves up to really learning.

I’m

sure, as a white male talking about feminism and racism, you have been

told that you have no right to speak about these issues. Can you talk

about your thoughts on who can legitimately contribute to these

conversations?

We’re organizing students of color around

ethnic studies, around anti-prison issues, around the over-policing of

our communities and the underresourcing of our communities, but there’s

so much resistance from so many white people who either refuse to

believe that this is a reality or accept that it’s wrong but that

there’s nothing that they can do about it. We need white people to

organize other white people who can relate their own experience about

coming to consciousness around these issues, to try to move and support

more and more white people to join in multiracial efforts and take on

injustice. For me, it’s always [about] trying to remember that it’s

absolutely important to amplify and support the voices and leadership of

folks of color. This is not about trying to get a bunch of white people

to fix the problem for everybody else. Racism is really a cancer in

white communities, killing white communities. [It] raises people to

racially profile others, to hate or be completely ignorant of other

people’s lives and experiences. For me, it’s less about taking [people

of colors’] stories and bringing them to white people, and more about

connecting with other people as a white person around: How can we come

to consciousness about racism, how can we overcome some of the barriers

that hold us back from becoming involved, and how can we make really

powerful contributions to working toward social justice and structural

equality?

Author, educator and organizer Chris Crass is often at the forefront of multiracial and feminist movements. Crass sat down with the Review this week to talk about his experience as an activist and his thoughts on antiracist organizing.

The topic of your talk, “Anti-Racist Organizing in White Communities,” is something that our college has been struggling with, both as an institution and as a student body. Could you begin by talking about the difference between racist and anti-racist organizing?

It’s a really common experience for white people who are socially conscious and who are coming to awareness about issues of race, particularly with the campus having the Day of Solidarity. There’s going to be a lot of folks — white folks in particular — being like, ‘Oh my God, I haven’t thought about this before,’ or, ‘I didn’t think it was this bad,’ or, ‘I thought this was something that was in the past,’ or ‘I don’t want to be part of the problem,’ and then one of the first next steps [ for those groups] is often the question of how to diversify. I’ve had a lot of experience being a part of mostly or all-white social justice progressive efforts where [that drive to diversify often comes first]. But the question that’s often more helpful is, ‘How can we be a part of challenging racism? How can we be a part of ending institutional white supremacy? What are positive steps, as a white environmental group, we could take to support environmental justice efforts by students of color?’ One of the ways that white supremacy really impacts white people is to invisible-ize the work that’s happening in communities of color, the leadership that’s happening in communities of color, the voices, the perspectives — sometimes you’ll have white activists come to consciousness about race and be like, ‘Oh my gosh, we have to get people of color to join our group,’ and then there’ll be activists of color who will be like, ‘Well, we’ve been working on these issues for a really long time, so rather than coming to us and asking us to diversify your group, it’s more of how could you, as a mostly white group, support the work that students of color are already involved in and build partnership and trust.’

What are some positive steps that Oberlin can take toward anti-racist organizing?

Some key ones are learning about work that’s already happen[ed] historically in communities of color, learning about issues. So if you’re in a social justice or progressive student group that’s mostly white, what are issues that students of color are working on, and what are some ways that your group can help support that work? A way that racism often operates is [by determining] whose voices are prioritized. Who’s been told all of their life, ‘You have an important story to tell. You should tell the world about what you think.’ And then there’s a lot of folks — women, queer folks, trans* folks, working class, folks of color — who are regularly told, ‘You have nothing useful to contribute. These aren’t spaces that you even belong in, let alone that you should be working in.’ [It’s about] working to recognize those kind of barriers and having open conversations with activists, leaders of color on campus about the struggles that [you’re] facing and how to think about it together. It’s not going to folks of color and [asking them] to solve all the problems but having genuine conversations about how to overcome these obstacles.

How would you explain the reality of institutional racism to someone who might not be familiar with its historical and cultural background?

No one was born with it all figured out. First of all, the way that racism operates is that it socializes and rewards white people to be completely ignorant of racism. The fact that there are so many white people who feel attacked, or who think that it’s racist to even talk about racism, is evidence of how powerful racism operates. Because in communities of color, historically and today, the impacts of racism are so stark. Often white people today look back at white people in the past — whether it’s the white people who were participating, supporting, oblivious [to] or on the sidelines of slavery, or white people who were supportive or on the sidelines of Jim Crow and apartheid in the sixties — and say, ‘How could they have just done nothing?’ [They think] it’s so obvious. People 30 years from now will look back on us today and say, ‘How could white people have not been aware of the mass incarceration, of the mass poverty, of the incredible disparities and not done something?’ As students, [we need to] recognize that we are historical actors, and just as we look on the past and think it was so clear, people will look back on our day and think that it’s so clear. Because in the past, people often said that it was too confusing, that there was no issue, that it was cultural. [We have to] recognize that we need to make a choice [about] what side of history we want to stand on. It can be a hard journey, but it’s one that ultimately connects us back to our deepest humanity. [We need to get] away from fear, away from ignorance, away from hate and toward a deeper love for ourselves and the people in our community. [People say,] ‘Well, the reason there’s so many black and brown people in prison is because of these reasons,’ and there’s all this justification in the way that the media portrays it, and throughout history that’s always been true. It wasn’t just this super clear cut obvious right and obvious wrong. So we need to take responsibility to investigate and learn and also to open ourselves up to really learning.

I’m sure, as a white male talking about feminism and racism, you have been told that you have no right to speak about these issues. Can you talk about your thoughts on who can legitimately contribute to these conversations?

We’re organizing students of color around ethnic studies, around anti-prison issues, around the over-policing of our communities and the underresourcing of our communities, but there’s so much resistance from so many white people who either refuse to believe that this is a reality or accept that it’s wrong but that there’s nothing that they can do about it. We need white people to organize other white people who can relate their own experience about coming to consciousness around these issues, to try to move and support more and more white people to join in multiracial efforts and take on injustice. For me, it’s always [about] trying to remember that it’s absolutely important to amplify and support the voices and leadership of folks of color. This is not about trying to get a bunch of white people to fix the problem for everybody else. Racism is really a cancer in white communities, killing white communities. [It] raises people to racially profile others, to hate or be completely ignorant of other people’s lives and experiences. For me, it’s less about taking [people of colors’] stories and bringing them to white people, and more about connecting with other people as a white person around: How can we come to consciousness about racism, how can we overcome some of the barriers that hold us back from becoming involved, and how can we make really powerful contributions to working toward social justice and structural equality? – See more at: http://oberlinreview.org/5225/uncategorized/off-the-cuff-chris-crass-author-activist-and-anti-racist-organizer/#sthash.5w2pEyva.dpuf

Author, educator and organizer Chris Crass is often at the forefront of multiracial and feminist movements. Crass sat down with the Review this week to talk about his experience as an activist and his thoughts on antiracist organizing.

The topic of your talk, “Anti-Racist Organizing in White Communities,” is something that our college has been struggling with, both as an institution and as a student body. Could you begin by talking about the difference between racist and anti-racist organizing?

It’s a really common experience for white people who are socially conscious and who are coming to awareness about issues of race, particularly with the campus having the Day of Solidarity. There’s going to be a lot of folks — white folks in particular — being like, ‘Oh my God, I haven’t thought about this before,’ or, ‘I didn’t think it was this bad,’ or, ‘I thought this was something that was in the past,’ or ‘I don’t want to be part of the problem,’ and then one of the first next steps [ for those groups] is often the question of how to diversify. I’ve had a lot of experience being a part of mostly or all-white social justice progressive efforts where [that drive to diversify often comes first]. But the question that’s often more helpful is, ‘How can we be a part of challenging racism? How can we be a part of ending institutional white supremacy? What are positive steps, as a white environmental group, we could take to support environmental justice efforts by students of color?’ One of the ways that white supremacy really impacts white people is to invisible-ize the work that’s happening in communities of color, the leadership that’s happening in communities of color, the voices, the perspectives — sometimes you’ll have white activists come to consciousness about race and be like, ‘Oh my gosh, we have to get people of color to join our group,’ and then there’ll be activists of color who will be like, ‘Well, we’ve been working on these issues for a really long time, so rather than coming to us and asking us to diversify your group, it’s more of how could you, as a mostly white group, support the work that students of color are already involved in and build partnership and trust.’

What are some positive steps that Oberlin can take toward anti-racist organizing?

Some key ones are learning about work that’s already happen[ed] historically in communities of color, learning about issues. So if you’re in a social justice or progressive student group that’s mostly white, what are issues that students of color are working on, and what are some ways that your group can help support that work? A way that racism often operates is [by determining] whose voices are prioritized. Who’s been told all of their life, ‘You have an important story to tell. You should tell the world about what you think.’ And then there’s a lot of folks — women, queer folks, trans* folks, working class, folks of color — who are regularly told, ‘You have nothing useful to contribute. These aren’t spaces that you even belong in, let alone that you should be working in.’ [It’s about] working to recognize those kind of barriers and having open conversations with activists, leaders of color on campus about the struggles that [you’re] facing and how to think about it together. It’s not going to folks of color and [asking them] to solve all the problems but having genuine conversations about how to overcome these obstacles.

How would you explain the reality of institutional racism to someone who might not be familiar with its historical and cultural background?

No one was born with it all figured out. First of all, the way that racism operates is that it socializes and rewards white people to be completely ignorant of racism. The fact that there are so many white people who feel attacked, or who think that it’s racist to even talk about racism, is evidence of how powerful racism operates. Because in communities of color, historically and today, the impacts of racism are so stark. Often white people today look back at white people in the past — whether it’s the white people who were participating, supporting, oblivious [to] or on the sidelines of slavery, or white people who were supportive or on the sidelines of Jim Crow and apartheid in the sixties — and say, ‘How could they have just done nothing?’ [They think] it’s so obvious. People 30 years from now will look back on us today and say, ‘How could white people have not been aware of the mass incarceration, of the mass poverty, of the incredible disparities and not done something?’ As students, [we need to] recognize that we are historical actors, and just as we look on the past and think it was so clear, people will look back on our day and think that it’s so clear. Because in the past, people often said that it was too confusing, that there was no issue, that it was cultural. [We have to] recognize that we need to make a choice [about] what side of history we want to stand on. It can be a hard journey, but it’s one that ultimately connects us back to our deepest humanity. [We need to get] away from fear, away from ignorance, away from hate and toward a deeper love for ourselves and the people in our community. [People say,] ‘Well, the reason there’s so many black and brown people in prison is because of these reasons,’ and there’s all this justification in the way that the media portrays it, and throughout history that’s always been true. It wasn’t just this super clear cut obvious right and obvious wrong. So we need to take responsibility to investigate and learn and also to open ourselves up to really learning.

I’m sure, as a white male talking about feminism and racism, you have been told that you have no right to speak about these issues. Can you talk about your thoughts on who can legitimately contribute to these conversations?

We’re organizing students of color around ethnic studies, around anti-prison issues, around the over-policing of our communities and the underresourcing of our communities, but there’s so much resistance from so many white people who either refuse to believe that this is a reality or accept that it’s wrong but that there’s nothing that they can do about it. We need white people to organize other white people who can relate their own experience about coming to consciousness around these issues, to try to move and support more and more white people to join in multiracial efforts and take on injustice. For me, it’s always [about] trying to remember that it’s absolutely important to amplify and support the voices and leadership of folks of color. This is not about trying to get a bunch of white people to fix the problem for everybody else. Racism is really a cancer in white communities, killing white communities. [It] raises people to racially profile others, to hate or be completely ignorant of other people’s lives and experiences. For me, it’s less about taking [people of colors’] stories and bringing them to white people, and more about connecting with other people as a white person around: How can we come to consciousness about racism, how can we overcome some of the barriers that hold us back from becoming involved, and how can we make really powerful contributions to working toward social justice and structural equality? – See more at: http://oberlinreview.org/5225/uncategorized/off-the-cuff-chris-crass-author-activist-and-anti-racist-organizer/#sthash.5w2pEyva.dpuf