By Clancy Sigal

guardian.co.uk

November 11, 2011

Ninety years on, the coal seams of West Virginia are a battlefield once more: for working people, the struggle goes on.

My first time in Westminister Abbey, London, I was taken inside by a coal miner friend who was down from South Wales for a brief London holiday. Suitably awed, we gawked at Poets’ Corner, the Coronation Throne, the tombs and effigies of prelates, admirals, generals and prime ministers—England in all its majesty and pageantry. Gazing at the Gothic Revival columns, transepts and amazing fan-vaulted ceiling, my friend said, “Impressive, isn’t it? Of course, it’s their culture not ours.”

Our culture—class conscious, bolshie, renegade—rarely lay in plaques and statues, hardly ever in school texts, but mainly in orally transmitted memories passed down generation to generation, in songs and stories. “Labor history” has become a province of passionately committed specialists and working-class autodidacts, keepers of the flame of a human drama at least as fascinating and blood-stirring as the dead royal souls in the Abbey. It belongs to all of us who claim it.

I’m lucky because my family’s secular religion is union. They include cousin Charlie (shipbuilders), cousin Davie (electrical workers), cousin Bernie (printers), my mother (ladies’ garment) and father (butchers and barbers), and cousin Fred (San Quentin prisoners). Establishment history may have its Battle of Trafalgar and Gallipoli; we have Haymarket Square, Ludlow, Centralia and Cripple Creek: labor’s battle sites, more often slaughtering defeats than victories.

Until recently, a lot of this history casually disappeared down Orwell’s “memory hole”, forgotten, censored or ignored. But with the spectacular emergence of the Occupy Wall Street movement, and fight-backs in states like Wisconsin and Ohio, young people especially seem to be regaining and reinvigorating a living history. Memory stirs.

This contest for memory is a class struggle by other means. Half our story—the half where unions created the modern middle class—is written in the pedestrian language of contracts, negotiations, wages and hours laws . . . the nuts and bolts of deals. After all, unions exist to make a deal.

But the other half is inscribed in the whizzing bullets, shootouts and pistol duels of out-and-out combat. Labor has its own Lexington and Gettysburg. And none more bloodily inscribed than in the hills and hollows of the West Virginia coal fields.

The 1921 five-day Battle of Blair Mountain was the largest domestic insurrection in the nation’s post-Civil War history, pitting 15,000 armed “redneck” miners, with their fierce and family passions, against an army of imported gun-thugs, strikebreakers, federal troops and even a U.S. army bomber, hired by the coal companies who owned the state and federal governments and believed they owned the human beings who dug the raw coal.

The Blair Mountain shootout had been preceded and provoked by the “Matewan massacre” when a local sheriff and his deputies, sympathetic to the young miners’ union, took on the coal company’s hired gorillas who were evicting pro-union miners and their families from their shanties. (See John Sayles’s film, Matewan.) Enraged miners marched on to Blair Mountain in the next county.

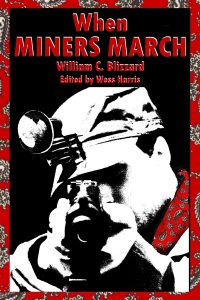

When the smoke cleared over Blair mountain, along an eight-mile front reminiscent of Flanders trenches, a hundred on both sides had been killed with many more wounded. Outgunned and under a presidential order, the miners, led by the fabulously named Bill Blizzard, took their squirrel-hunting rifles and went home—to face indictments for treason and murder, drawn up by the coal owners and their bought judges. Sympathetic juries freed most of them. (For further interest: Bill Blizzard’s son, the late William C, has a book, When Miners March.)

The beautiful, heartbreaking thing is that today the Battle of Blair Mountain goes on. With protest hikes, films and pamphlets, the campaign to save the mountain—again—sets local miners and their families and friends, including archaeologists and historians, against West Virginia coal owners like notorious Massey Energy, still being investigated by the FBI for possible criminal negligence in the deaths of twenty-nine miners in the Upper Big Branch disaster of 2010.

A billion dollars of undug coal inside the mountain is at stake. The world is in the middle of a coal rush. Dynamite is cheaper than people. Incorrigible companies like Massey aim to blow up Blair, via “mountaintop removal” (aka “strip mining on steroids”), to get at the coal and, while they’re at it, destroy the people’s battleground, the ecology and any inheritance of resistance.

It is a fight over memory and honor, with very practical consequences for the coal valleys, its displaced families, poisoned rivers, contaminated communities. For a while, it looked as if the miners and their union had won a great victory by getting Blair Mountain on the National Register of Historic Places. But with a Democratic state governor and a Democratic president refusing to take sides, the coal owners—who still control West Virginia—at the last minute suddenly found some landowners to object. With the connivance of Obama’s departments of interior and environment and the Park Service, Blair Mountain was de-registered and thrown open to the pillagers.

Coal mining is where open class warfare is often at its sharpest, most visible and violent. Something about the job underground, and the shrewd tactical skills it takes not to get yourself killed by roof falls and methane gas explosions, binds miner to miner in what the military likes to call “unit cohesion.” Historically, miners worldwide have been in the advance guard of social progress. It’s one reason why coal companies in America, and Mrs Thatcher in Britain, always despised the miners and became obsessed with breaking their union.

Labor does not have its Westminister Abbey and probably shouldn’t. Museums are no substitute for “talking union.”