By Martin Wainwright

The Northerner Blog

March 5th, 2013

John Rylands Library

plays host to tributes from artists and writers to al-Mutanabbi

Street, where freedom of expression was targeted by bombers five years

ago

Six years ago a bomb blew free speech to smithereens in the Street of Booksellers in Baghdad, an institution whose roots ran right back to the House of Wisdom in the 9th century Caliphate where the learning of the classical world was preserved and enhanced.

The explosion killed 26 people and wounded over 100 but stood out particularly from the general misery of Iraq at the time as a vengeful and deliberate assault on a place of learning and debate which had survived repression and dictatorship for centuries.

A

man stands amid rubble just after a suicide car bomb exploded in

al-Mutanabbi Street, a deliberate attack on free speech whose

organisers have not yet been traced. Photograph: Khalid Mohammed/AP

A survivor told a Washington poetry festival in 2010 how he lay wounded in the storeroom of the bookshop where he worked and staring up through a hole blown in the roof at “thousands of small gray ashes—pieces of paper, books, newspapers—floating down from the sky.” Those ashes did not, however, die. They proved to be embers which have made the street more famous outside Iraq than ever before.

Although the actual buildings, reopened by Iraq’s Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki five years ago, now contain many toy stores and fewer bookshops, a parallel and much larger version has been created internationally in the minds and work of writers and artists. The winding lane’s actual name of al-Mutanabbi Street honours a tenth century poet whose pen was silenced by an enemy insulted in one of his verses; the bomb, whose perpetrators remain unknown, was a similar attempt at censorship which free spirits resolved to challenge.

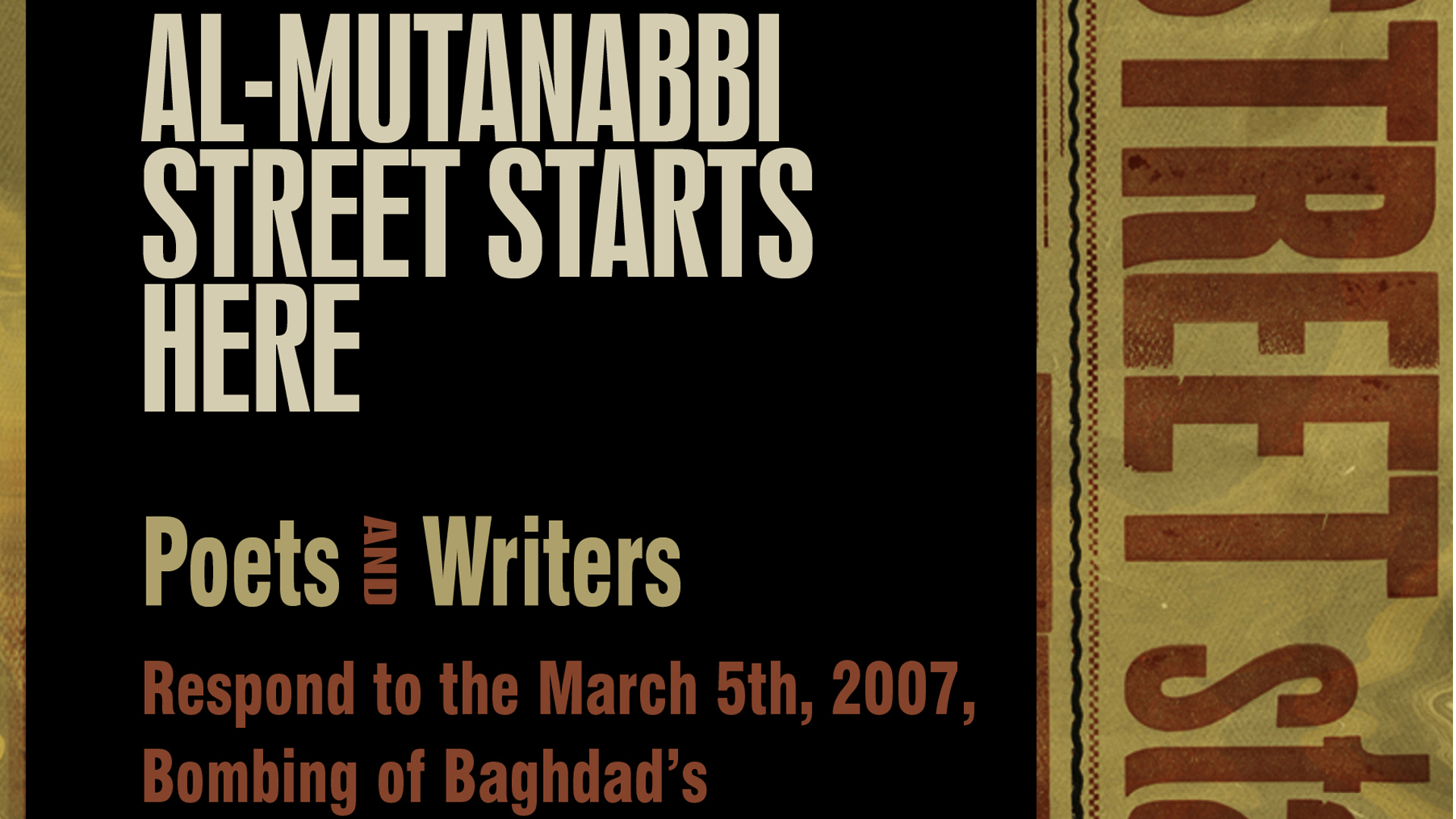

Their work has been co-ordinated by a group called the al-Mutanabbi Coalition which was prompted in the immediate aftermath of the attack by a poet and bookseller in San Francisco, Beau Beausoleil, whose network of contacts responded with zest. Gatherings, debates and memorials both written and artistic followed, and now the biggest collection of them has gone on show in the UK, which is a centre for a singularly appropriate tribute: the Artist’s Book.

The main reading room at the John Rylands Library, the gift of the Cuban widow of Manchester’s first millionaire.

Photograph: Christopher Thomond for the Guardian

Approaching 150 of these fill exhibition cases in Manchester‘s John Rylands library and more are arriving there every day. The collection, entitled An Inventory of al-Mutanabbi Street – Building with Books, moves on to San Francisco and New York later this year and thence to Switzerland, Canada, Egypt and eventually the Iraq National Library in Baghdad. But the John Rylands is an approriate starting place.

Built to enshrine free thinking and public access with the money of a Liberal cotton merchant by his Cuban widow, it co-operated enthusiastically with the Coalition’s first initiative, a set of 130 international ‘broadsides’ which responded to the bomb in the vigorous tradition of 16th century Tudor pamphleteers. Encouraging these, Beausoleil drew unconsciously on a metaphor which the poet Muttanabi also used. He spoke of writers ‘biting into the page’ in defiance and anger. Muttanabi warned in his day: ‘If you see the teeth of a lion, do not imagine that they are smiling at you.’

A John Rylands series of events around the broadsides in 2011 included a talk entitled Any Street, Anywhere by Sarah Bodman, the UK curator of the current exhibition and senior research fellow for Artists’ Books at the University of West England in Bristol. Sorting through the exquisite little tributes, which use ash, blank pages, excerpts from the classics and scribbled messages, she calls them: “A resounding echo, a compassion for our fellow community of writers, artists, printers, booksellers, browsers and passers-by on al-Mutanabbi Street.”

One of the delicate ‘artist’s books’ which are a testament to the world’s determination to protect free speech

The tributes include much anger but also a gentleness which is equally powerful, for example in a correspondence which is fictional but based on the reality of the street during some of modern Iraq’s worst times. The Welsh book artist Noelle Griffiths submitted Beloved Bashir, in which an ageing Baghdadi woman posts requests to her bookseller such as: “Please bring me a copy of the magazine Vogue. I want to remember what it feels like to be attractive.”

Bodman says that the glory of the street was not only its rare reputation for free political debate but the availability of the sort of huge hotch-potch of publications which have made a similar name for places such as Greenwich Market or Charing Cross Road. The Iraqi writer Lutfia Alduleimi, whose first book was published by al-Jahiz printers on the street, echoes this. She says:

Who among us had not been enticed by the magical stacks of books on the pavement and in carts, or walked awestruck, browsing titles and sniffing the scent of the pages? Who could forget the pleasure of buying new books in the 1970s, or banned or xeroxed books in the nineties during the period of sanctions?

Others went to buy pencils, children’s exercise books or comics, or just to have tea of coffee in one of the many cafes whose lineage was almost as old as the booksellers’.

The exhibition is at Manchester until 29 July, with free admission, and at the Newcastle Lit and Phil library in August, and will repay repeat visits because books keep being added. Bodman says:

One set of books will go to the national library in Baghdad within the next few years but we have no idea when the international tour by the others will finish. Probably never. Because this attack, part of a long history of attacking the printed word, was an attack on us all.

You can see Christopher Thomond’s picture gallery on the exhibition for the Guardian Northerner here.

Back to Beau Beausoleil’s Editor Page | Back to Deema Shehabi’s Editor Page