By Jonathon Green

The New Statesman

27 August, 2001

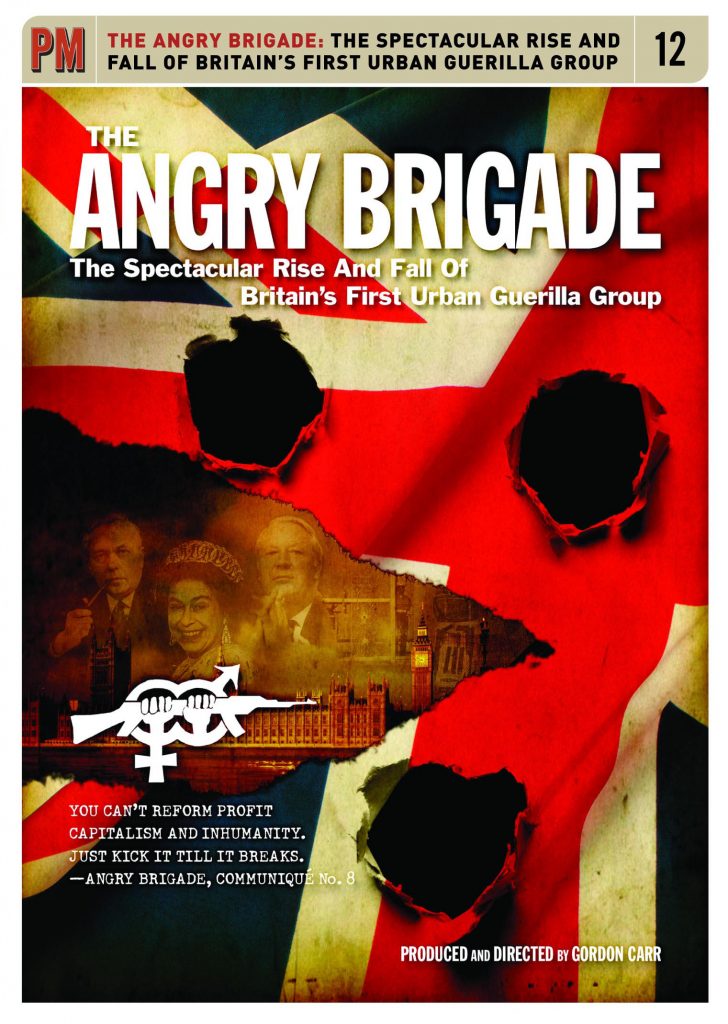

In the late Sixties and early Seventies, the Angry Brigade enraged the establishment. Jonathon Green on the questions that remain unanswered 30 years on

“The Angry Brigade is the man or woman sitting next to you.

They have guns in their pockets and hatred in their minds.

We are getting closer. Off the system and its property.

Power to the People. Communique 9. The Angry Brigade”

(22 May 1971, following the bombing of Tintagel House)

Thirty years ago this month, on 20 August 1971, police swooped on a flat at 359 Amhurst Road in Stoke Newington, north London. Whom and what they found there would lead, nine months later, to one of Britain’s longest political trials, see four young people start ten-year jail sentences and, it was believed, end the career of the Angry Brigade – this country’s contribution to that international phenomenon of the Sixties and early Seventies, the student urban guerrilla group.

Yet for all the excitement it provoked at the time, and the endless recycling of that era, this particular episode seems almost to have vanished from history. The arrests were made barely weeks after the end of another celebrated trial, that of the editors of the underground magazine Oz, a tale that has been recreated for the stage, for television and in endless memoirs. The Angry Brigade trial, and the bombings that led to it, were equally momentous, yet there are no dramas, no memoir. As far as history goes, the Angry Brigade is barely a footnote.

Between 3 March 1968 and 22 May 1971, England suffered a campaign of around 25 bombings. The targets included senior politicians and policemen, captains of industry, a fashionable boutique and the Miss World competition, a Territorial Army drill hall in north London and the Metropolitan Police computers. There were no fatalities and, at first, no identifiable bombers. The latter changed when the first of a series of “Communiques” was issued, following a bomb at the home of police commissioner Sir John Waldron in August 1970. It was signed by “Butch Cussedly and the Sundance Kid”.

The next communique stayed in the Hollywood West, coming from “the Wild Bunch”. However, on 12 January 1971, when the target was Robert Carr, the Tory secretary of state for employment and productivity, and chief advocate of the highly controversial anti-union Industrial Relations Bill, the signature, stamped with a children’s John Bull printing kit, read “The Angry Brigade”. The name remained thus for every explosion that followed.

If the earlier attacks had mystified police, and been underplayed in the media, the game changed when the target became a government minister. The establishment, urged on by the then prime minister, Edward Heath, mounted a frenzied, and often desperate, response: the Brigade was to be “smashed”. There were six more bombings, each followed by ever more intensive police activity, before, thanks to tip-offs and investigative work, the police made their arrests.

At the north London flat, they claimed to have found a quantity of guns and explosives, and reams of paper covered in lists that seemed to be plans for future attacks and notes for political pamphlets. In all, the jury was presented with 688 pieces of forensic evidence, from a Beretta sub-machine gun to “an unidentified substance from foot of tree in garden rear of door”; they included letters, batteries, political literature, a vehicle-licensing application, a cache of gelignite, the detonators to ignite it, address books, letters, counterfeit US dollars, Angry Brigade communiques and much more.

Perhaps most damning was the discovery of the John Bull stamp, still bearing the incriminating words “Angry Brigade”. The police also found four people: John Barker, Hilary Creek, Jim Greenfield and Anna Mendelson, and arrested the lot. Within 48 hours, a further four suspects were in custody: Stuart Christie, Christopher Bott, Angela Weir and Kate McLean. Despite lengthy interrogations, all maintained their innocence and never abandoned that position during the following nine months of investigations. On 30 May 1972, they pleaded “not guilty” as they stood in the dock of the Old Bailey’s number one court. What followed was the 20th century’s longest political trial (however fervently the authorities attempted to deny the adjective). A blanket “conspiracy” charge – active participation was irrelevant, explained the judge; mere knowledge, even “by a wink or a nod”, was sufficient proof of guilt – in effect made any direct defence unsustainable.

On 6 December that year, the trial ended with convictions for Barker (who defended himself with great sophistication), Creek, Greenfield and Mendelson, and acquittals for the rest. The jury’s appeal for clemency ensured that the four got ten-year sentences, rather than the possible 15 years. The women served less than five; the men were out in seven.

Thus the bare bones. Yet, 30 years on, the Angry Brigade remains the lost event of “the Sixties”. That the defendants have consistently refused to reminisce has not helped. Only John Barker, who has described himself as “a guilty man framed up”, has ever commented, and then only in a book review. The rest are silent, rarely contacted and, when uncovered, adamant in main-taining their tight-lipped anonymity. Nor has anyone from their support group – among whom, it was believed, might be further Brigade “members” – broken cover. As they have all made clear: that was then, this is now. There is no desire to revisit the past.

Such reticence, seemingly precious in this self-aggrandising age, doubtless springs from many sources, among them the dislike of being lumped into the cliched images of the Sixties. But the Brigade was as essential a part of that loved and loathed era as the “swinging” Biba boutique it bombed. Along with the period’s giddy aspirational triumvirate – “dope, rock’n’roll and fucking in the streets” – came the symbiotic, if inchoate, “revolution”. This took many forms, whether articulated by the severe apparatchiks of the New Left or on the wilder shores of freaked-out hippie fantasy. At its extreme came the urban guerrillas, as international a phenomenon as more hedonistic excitements. America offered the Weathermen, Italy the Red Brigades, Japan the Red Army Fraction, Germany the Baader-Meinhof gang. At home, we had the Angry Brigade. Like their international cousins, they were alienated children of the bourgeoisie, seeking to create a new world not through easy yet ultimately ineffective words, but through hard, destructive action.

Their roots lay in such groups as the French Situationists, who ranted against “the society of the spectacle” (or what the New Left’s guru, Herbert Marcuse, termed “repressive tolerance”), and London’s anarchist King Mob group, which at demonstrations countered chants of “Ho, Ho, Ho Chi Minh!” with the derisive “Hot Chocolate, Drinking Chocolate!”. The Angry Brigade professed no easily identifiable ideology. As with today’s anti-globalisation protesters, “membership” of the Brigade depended as much on a state of mind as on any party card. If you agreed with them, noted one of the more perceptive policemen, you were a member.

Indeed, for all the “forensic”, for all the millions of words given in evidence, the trial, while it satisfied a need for closure, was ultimately unsatisfactory. There were, for instance, no fingerprint links to the weapons or explosives, which led to vehement suggestions of police “planting”. Nor did any of those arrested test positive for traces of explosive. And the bombings had not stopped with the arrests: there were two more, including that of the then GPO Tower, even as the defendants sat in jail. To believe that just four people conducted the whole campaign was surely the most wishful of thinking. As the Observer put it at the time, “far more questions [were] raised during the . . . trial than were ever answered”; and, as the defence counsel Ian Macdonald noted, until the four write their memoirs, the truth will remain obscure.

Hindsight makes it easy to dismiss the effect of the Brigade. For some, its “adventurism” was simply one more futile way station on track to Margaret Thatcher and Tony Blair. The Brigade’s hopes for change proved as empty as the hippies’ nirvana and the New Left’s Marxist pieties. Others have suggested that in its restraint – its European peers left corpses – the Angry Brigade was overly “English”. Barker himself has suggested that “we were not that serious” (his emphasis) and that, as romantic young people, they believed “nothing very terrible could happen to us”. But, like the Oz editors before them, the Brigade underestimated the ruthlessness of an establishment under threat and suffered for their ignorance.

But they were serious: that they moved from rhetoric to action, with all that followed, is undeniable. And to explode non-lethal “infernal devices” (as the forensic experts apparently still termed the bombs) is perhaps even more sophisticated than simply blasting indiscriminately.

We live in an era of celebrations and anniversaries. Yet the silence of the participants and their supporters, and the amnesia of the media, have left this bit of Sixties/Seventies memorabilia gathering dust in the attic. None the less, once upon a time, a band of urban guerrillas turned Britain upside down.

As another Four from that era put it: “It was 30 years ago today . . .”—Will Self, page 37

Jonathon Green, the author of two books on the Sixties, is preparing a radio programme on the Angry Brigade

Countdown to conviction

1969

August: Home of Duncan Sandys, Tory MP, firebombed

October 15: Firebomb damages Imperial War Museum, London

1970

August: Home of Sir John Waldron, Metropolitan Police commissioner, damaged by bomb blast

November: BBC van bombed outside Albert Hall after covering Miss World contest

December: Bomb at Department of Employment and Productivity claimed by Angry Brigade

1971

January: Home of government minister Robert Carr bombed

April: Times receives letter bomb and message from Angry Brigade

May: Biba boutique in Kensington bombed, claimed by Angry Brigade

June: Times receives letter from Angry Brigade threatening prime minister Ted Heath with bullet

August: Intensive police raids on activists’ houses; explosion at army recruiting centre in north London, claimed by Angry Brigade

August 21: Police raid at Amhurst Road. Four arrested; four more (later acquitted) are arrested throughout day

August 23: “Stoke Newington Eight” charged and held.

1972

May 30: Trial begins

December 6:

Barker, Creek, Greenfield and Mendelson are sentenced to ten years for

“conspiracy to cause explosions”. Jake Prescott had earlier been

sentenced to 15 years for conspiracy to cause bombings