by George Caffentzis

GODS & RADICALS

August 4th, 2015

Report From Greece, Part 1

From Thessaloniki to Iraklion

Summer 2015

In the summer of 2015 I spent a month in Greece, from June 10 to July 10. I travelled from Thessaloniki to Volos to Athens to Sparta to the Mani to Crete then back to Athens. I stayed mostly with comrades, some new, some old and I was joined for ten days by Silvia Federici. What follows are some observations and comments on this tumultuous period that included the “OXI” (“NO!”) referendum, innumerable meetings of the “Troika” [ed note: the triumvirate representing the European Union in its foreign relations] with and without the officials of Syriza, the coalition of leftist parties that took over the government in January 2015 after being a tiny party for decades [ed. note: or, the Greek Coalition of the Radical Left, name taken from the Greek adverb “from the roots”]. Though the sections are undated, they are roughly placed in a chronological order. This is not meant to be a comprehensive account of the situation in Greece, so there are many facets of the class struggle there that are not noted. But I should point out that the immigrant workers are part of the Greek working class.

Greece 2015: Setting the Stage

The following is what I can make of collective understanding of the crisis put together with the help of comrades from Greece and the U.S. (in my own words, of course):

There are two levels to the crisis. First is the visible financial balance sheet level. Here is the world of debt payments due, say X, and the largely tax-based income of the state, say Y, and X-Y is what is due and it is huge amount. The drama of money, part tragedy, part comedy, is played out, with the protagonists in the front of the stage (incarnated by the financial wizards of the troika, the “young” P.M. Tsipras and the now ex-finance minister Varoufakis) while in the background is a shadowy chorus of bond-holders and out-front vulture hedge-fund managers who intervene periodically with sibylline utterances full of threat and fury.

The second level is the unstated but persistently followed plan to use the first crisis of state finances (the debt crisis) to put the European proletariat into crisis by making the elimination of labor legislation favorable to workers, the cuts in pensions, increased unemployment and a dramatic decrease in wages as structural adjustment conditionalities for any new “bailout” loans. The Greek working class is simply the supposed “weak link” useful for carrying out the plan aimed at Europe as a whole.

This is why the “fictive capital” theorists are so unconvincing. If the structural adjustment program elements of the plan were missing, then there would be a “financial solution to a financial problem.” But the clear purpose of the financial crisis is to deal with the fall of profitability in the entire European region. Capitalist strategists believe that the levels of wages, alternative forms of work refusal (pensions and welfare benefits) and of reproductive “services” (health and education) are so high that they make it impossible for European-based capital to compete (especially with Asian and North American capital). The crisis managers’ aim is to normalize the cuts in these levels and to make such a working class existence (precarious wages and even a return to testing physiological limits) a feature of the standard of living in Europe for the foreseeable future. If this is not done, European capital will suffer what at first may look like euthanasia, but then will later precipitate into a violent dissolution. This is the crisis of European capital! So not only are the European proletarians in trouble, but so are the capitalists. There are many crises in the field, there is no THE crisis.

All Quiet on the Extra-Parliamentary Front

There is something remarkable happening in Greece with the victory of Syriza in the elections of January 2015. A left-wing party gets into state power, but it seemed to have definitely kept the rest of the Left (parliamentary and extra-parliamentary) from using this time to put forward their own programs and demands in the streets. This seems to confirm Raul Zibechi’s insight, coming from Latin America, that the only force that could now defeat the anti-capitalist social movements is a left-wing government in power (or on its way to power).

I sensed a definite loss of direction, of energy, of confidence in the last few years within the extra-parliamentary left. Between December 2008 and April 2012 there was a period of intense confrontation with the forces of the state run by right-wing parties proposing austerity as a way out of the crisis. Along with this was the direct confrontation with Golden Dawn, the Greek version of the German Nazi Party [ed note: this is not the Hermetic Order Of The Golden Dawn, familiar to many pagans & occultists]. Both were very popular antagonists.

But the rise of Golden Dawn was halted by its members’ assassination of a popular leftist rap singer that brought out a tremendous response. The right-wing government at the time then recognized that the Golden Dawn was too dangerous to let it expand without some checks. Without the antagonistic presence of Golden Dawn, however, the raison d’etre of much alarm and sense of emergency was vanishing in the fall of 2014.

Syriza’s sudden rise to state power (with its pledge to end the austerity regime imposed by the “the troika” and its minions in Greece) was also disconcerting for the extra-parliamentary left, since Syriza’s success implied that there might be an electoral way out of the regime of poverty and tatters.

Together these two developments disarmed the critics of electoral solutions to the crisis. So now in the face of an unprecedented attack on living standards, we see very little response in the streets. Syriza is therefore receiving negative support from the extra-parliamentary left.

Moreover, on the extra-parliamentary front, there is much division and backbiting typical of a period of defeat. I cannot help but be skeptical of the appeal of the extra-parliamentary left’s political program when I compare the number of youths involved in the simple commodification and consumption of sociality, sexuality and general pleasure in the cafes and tavernas —as if they are thumbing their collective noses at the troika! What a display of the willfulness of enjoyment that inserts a new pole of attraction in the equation…a pure anarchism.

As I walk through downtown Thessaloniki in the soft evening air I wonder, am I on the deck of the Titanic or am I walking through Paradise?

A clear-headed Anarchist from Thessaloniki speaks:

- The solidarity economy is not strong enough yet to take on the task of social reproduction.

- The collapse of the Syriza government would lead to an extremely repressive right-wing replacement.

- Doing cooperative labor is not easy. Multiplying our experience with a cooperative bookstore would definitely be a lesson.

ERT3 confronts Syriza

Silvia Federici and I were invited to a meeting of workers at the national radio and television (ERT3) station in Thessaloniki. It was shut down exactly two years ago by the troika-friendly Nea Democratia-PASOK government that was looking to do something dramatic to show the bondholders that it was serious in sticking to the structural adjustment agenda. The shut-down decision was made abruptly and disrespectfully, with accusations of laziness and corruption tossed around to justify it. But the workers refused to exit silently. They faced down the police with the help of a crowd that blocked the entrances to the station and they continued to work in their studios and offices with live news, opinion and entertainment programing. In the evening and early morning there were documentary programs and re-runs. So that the station provided a 24/7 presence via the internet with programing especially keyed to the interests of the Northern Greek and Balkan audience. They did all this without pay and with donations from their listeners.

When Syriza came to power in January 2015 its spokespeople promised to revive the public broadcasting system and rehire all the journalists, technicians and office personnel that were laid off in 2013. This was the day when everything would be regularized with the arrival of the newly appointed station manager from government headquarters in Athens. However, not all was well as far as the workers were concerned.

First, the ERT3 workers have been used to self-management after two years of making decisions on the basis of assemblies of workers. In fact, that is exactly what they did on the arrival of station manager. They invited him to their assembly to debate with him as to his instructions from Syriza headquarters in Athens.

Second, they had learned one of the first acts of the new station director would be to lay-off or not-hire anyone that had joined the effort to keep the station alive in the previous two years.

Third, they were not happy that the new station manager was a former official of PASOK. Why wasn’t someone more in line with the politics of Syriza sent to become station manager? Or, what is Syriza’s politics now in the first place?

At the workers’ assembly there was talk about going on strike to protest the threatened lay-offs. In response, at the very moment when the rest of the workers would be getting a pay-check for the first time in two years, there was much dramatic rhetoric on the theme of the importance of ERT3’s programming, in support of the argument that the station should not go on strike (since ERT3 is often the only news channel that covers the strikes of others)!

Talk in Volos

After a number of talks in Thessaloniki by George and/or Silvia, here are notes for a joint talk in the Architecture school in the University at Volos:

From Debt To Crisis To Enclosure of the Commons

What is happening in Greece is the implementation of a structural adjustment program (a technical term that became so hated around the planet that the World Bank and IMF stopped using the term to be replaced by the term “Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper”!) as it was applied to former colonized states that have taken their mandate from the anti-colonial movement seriously. They were posing a threat in claiming the New International Economic Order (NIEO). This was a serious challenge (of which the nationalization of the oil industry across the planet was an example). The NIEO was in effect claiming reparations for colonialism’s massive theft of land, mineral wealth and labor-power. This was getting too close to the old masters’ bone and had to stop! To do this a trap was prepared, a debt trap. The governments of the former colonial world were tempted to take out loans with variable interest rates which at the time were relatively low, to fulfill the very mandate of ending the poverty and degradation of the last century. The trap was sprung in 1979 (under the rubric of “stopping inflation.”). The interest on the loans rose to nearly 20% over night. The former colonized countries’ governments were trapped indeed facing a debt crisis!The IMF and WB acted quickly. They did not want to lose the opportunity the crisis provided by dealing with a financial problem by financial means (e.g., rolling over the debt for another year). On the contrary, they imposed structural adjustment conditionalities that were directly aimed at the elimination of the commons (since most of these SAPs had requirements involving the land ownership and the transformation of commons into private ownership and other goals that were meant to privatize what were considered common goods (from pensions to “royalties” on extracted wealth. So here we have a direct line from Debt to Crisis to the Enclosure of the Commons.

Like a Frenzied Dog on a Trapped Fox

A similar path can be traced in the application of this scenario to Europe, starting with Greece. This is a period of low interest rates and there is much lending, but it is also a period of low profits as well. Greece became part of the Eurozone under the assumption that the inevitable restriction in monetary policy required by the single currency would be compensated during a crisis (e.g., roll overs of the debt would be allowed). This was a mistaken assumption, since it was not assumed by the European Central Bank, the European Commission and the IMF. So a trap was closed on European countries like Greece and a package of structural adjustment policies was unleashed like a frenzied dog on a trapped fox. These policies were directed at commons and commons-like institutions (from pension funds to revenues from the extraction of mineral wealth) in preparation for the TTIP (the Trans-Atlantic Trade and Investment Partnership). These specifics are driving the clear investing in silver 2016 that we are expecting.

An Autonomy Crisis

The reactions from the working class of Europe was tumultuous, and a new version of “IMF riots” were chronicled throughout Europe from 2010 on. But there hasn’t been any break through. The working class of Europe is experiencing a crisis of its power to say “No!”…i.e., an autonomy crisis that the OXI vote of July 5 might signal an anti-capitalist resolution.

Family and Poverty Reduction

The most effective poverty reduction institution in Greece is still the family. Though the family capital is being depleted at a rapid rate, it has been the cushion for the hard landing many have individually experienced these last five years. I’ll always remember my cousin’s table for Sunday lunch, everyone, four generations, eating elbow to elbow, frustrated each in their own ways, but all with a full belly! In fact, there is a race between state capital with family capital to determine which will be depleted first. If families’ savings get exhausted first, there will be genuine food riots that hadn’t been seen since the 19th century. If state capital exhausts first, there would be an anarchist turn in the creation of social reproduction institutions (from health clinics to Community Supported Agriculture agreements).

Cash in the Mattress and the Increase in Burglaries

There is much suspicion of banks and other financial institutions in Greece. There haven’t been any serious runs on the banks YET, but there is a walk from them. This explains the dramatic increase in the hoarding of cash under the famous mattresses. This has led to an increase in the number of burglaries, since burglars read the financial news as well! There is even a burglar’s demand for machines that locate gold coins!

A Fashion Statement

There is a strong taste for the tattered jeans, shorts and t-shirts this summer in Greece. Is this a fashion commentary on the crisis? Is this a way of merging the inside with the out? While sitting in the central square of Sparta, I see a little two-year old dressed with torn jeans. This fashion statement is a reminder of a change in the frankness of expression, because when I was a child on the Sparta square, the parents and children were dressed to a “t,” even though the poverty of the 1950s was much deeper than today’s.

Plato’s Republic and Debt Refusal

In the midst of the debt crisis in Greece, Joulia Strauss, a German artist, decided that it was time to bring artists, scholars, political activists to Greece to show their solidarity with the Greek people in crisis. She thought a free school would be the best way to express this solidarity and the best venue for the school would be the site of Plato’s Academy (a few stones remain of it, rescued by archeologists). A. contacted me, recommended Joulia’s project and so I joined. I thought a presentation of Plato’s views on debt payment refusal would be a suitable topic. Then on the 23 of June a small band (reaching twenty at its peak) made its way to the site of the Academy and I made my presentation. The following is the text I based my remarks on:

June 23, 2015 at Plato’s Academy

Everyone would surely agree that if a sane man lends weapons to a friend and then asks them back when he is out of his mind, the friend shouldn’t return them, and wouldn’t be acting justly if he did.

Plato, Republic 331c.

In the fall of 2011, just after the termination of Occupy Wall Street, I began speaking in support of those who had pledged to refuse to repay their student loan debt once a million others have also pledged to do so (under the rubric of Occupy Student Debt Campaign). In the course of giving a number of presentations concerning this campaign I received many queries and criticisms. The queries were most often practical, e.g., “what about co-signers, what will happen to them if I refuse to pay when I become the millionth and first student loan debt refuser?” The criticisms were also practical, ranging from “why not organize people to refuse all debt?” to “if you refuse to pay student loans debt, wouldn’t the Federal Government stop supporting the student loan program at all and hence you would harm future students?” I was prepared to deal with these practical questions and criticisms on their own terms, with empirical evidence and political argument.

But there was a more problematic criticism that was not so easily answered, since those who voiced it were not just in disagreement with the premise of the campaign–it was justified to refuse to pay a student loan debt– but they were morally offended by it. Their retorts to my arguments for the Campaign took on an almost metaphysical aura of sanctity when they spoke about the importance of paying debts from loans that were freely entered into, whatever the consequences. Their criticism quickly left the plane of facts and even values and entered into a world of meta-values with the primary one being: one cannot be morally serious unless one pays back one’s debts.

The political problem posed by this moral attitude to debt repayment is that it touched a raw nerve in many student loan debtors who have been ashamed by their inability to pay off their loans. This shame has led many to try to cover up and not talk to others (even family members) about their plight. According to my research concerning previous student loan debt abolition efforts, one of the key reasons they have not been successful has been their inability to overcome debtors’ characteristic shamed silence that is profoundly anti-political because it turns the collective problem of debt repayment into an individual issue to be dealt with one person at a time. Consequently, this moral criticism had to be dealt with directly and decisively if the anti-student debt effort was not to meet a similar fate, since this criticism not only makes it difficult to move the critics, but it has a problematic effect on many debtors who are already vulnerable to the mental blackmail implicit in the “debt moralists’” assertions.

In thinking through the conundrum posed by these debt moralists, I realized that, as a philosopher, I was equipped to deal with the philosophical arguments for or against student loan debt repayment. The more I explored the literature the more I realized that the defense of debt refusal has a long philosophical history. It was important to get this literature into the contemporary discourse on debt in response to the rigidity of debt moralism.

If Plato’s Republic marks the beginning of political philosophy, then debt payment refusal appears at the beginning of the beginning of political philosophy. Plato, the aristocratic darling of conservative thinkers, actually defends debt payment refusal in the Republic. Plato’s concern with debt should not be surprising, since indebtedness leading to debt slavery was the source of civil wars and revolutions throughout ancient Greek history from 600BC on. Solon, the famous Athenian law-giver, aimed to stop the endless turmoil caused by the cycle of debt-enslavement-revolution-debt and the ever reigniting class war between the poor debtors and the creditor plutocrats that was leading Athens to catastrophe. He did so by legislating the end of debt slavery, a move that led to the democratization of the Athenian state, and increasingly the remuneration of citizens for their public work (especially for their participation in the administration of justice and legislation, which required attending general assemblies and being part of juries, like the jury of 800+ that decided Socrates’ trial).

Solon was a politician and even a sage, but he was not a philosopher. Plato was. What did he have to say about debt repayment refusal? Significantly, the discussion of debt at the very beginning of the Republic. The first person Socrates interrogates, posing the book’s germinating question “What is justice?” is Kephalos, a wealthy arms manufacturer — although an immigrant, a member of the Athenian 1% — and owner of the house where the dialogue staged in the Republic is supposed to take place. The name “Kephalos” itself is important, for in ancient Greek it meant “head,” and as such it is a cognate of the word for “capital.”

Kephalos’ answer to Socrates’ question, appropriately enough for a merchant, is: “Speak the truth and pay your debts!” But Socrates easily dismisses this definition, pointing out that if a person borrows some weapons from a friend, but in the interim the friend “goes berserk” and becomes (murderously and/or suicidally) insane, it would not be just for the debtor to return the weapons to the friend…in fact, repaying the debt in this circumstance would be positively unjust, since it would lead to either murder or suicide or both! Thus the conditions of just repayment of a debt do not necessitate an absolute commitment to repayment under any conditions. Universalizing the kernel of Socrates’ rejoiner to Kephalos’ definition, we come to the following maxim: one should refuse to repay a loan when the payment will lead to evil or unjust consequences that far outweigh what fairness would result from its payment.

Plato’s suspicion of Kephalos’ wisdom was the outcome of the Athenians’ long political experience with a class of merchants and landlords who, like Kephalos, insisted that their loans should be repaid even if this should result in debt-slavery and class-based civil war. This may explain why, in Socrates’ response, Plato referred to the loan of a weapon! For creditors in this case appear to be a maddened crowd, with debt repayment being a cause of murder and suicide, especially when ending with the enslavement of fellow citizens.

These issues did not die with the end of the ancient world. Indeed, today’s “debt moralists” offer a response to those who refuser student loan repayment similar to the one that Kephalos made to Socrates’ query. In turn, we too must respond to the categorical imperative of debt moralists in the same way that Socrates responded to Kephalos’ definition of justice, with an emphatic “it depends.”

First, it depends on whether student loans are unjust in and of themselves qua loans. On this count, the actual mechanisms of student loan debt speak decisively. For a start, student loan debts in the US cannot be discharged through bankruptcy, unlike almost all other loan debts can be. In addition a large percentage of these loans have been contracted under fraudulent conditions, as it was revealed in the course of frequent scandals, court cases and Congressional committees’ investigations. As Robert Meister pointed out in the case of the University of California, UC administrators pledge future student fees largely to be paid for by student loans and grants to support UC’s bond ratings, its capital projects and a variety of equity deals that turn public money to private gain. This territory has been thoroughly explored by previous student loan debt abolition movements and there is still a lot more to learn.

Second, it depends on whether the collective good is served by repayment. Here it is important to understand the function of student debt in the context of the changes that have taken place in university financing since the 1970s. The ever increasing student debt burden (now beyond one trillion dollars) has been the material condition that made the imposition of ever increasing tuition fees in both public and private non-profit universities possible and financed the expansion of for-profit universities. These developments have led to the corporatization and privatization of universities, on the one side, and plunged a whole generation into debt-bondage. There is no doubt, therefore, that restoring a tuition-free university system and avoiding a further polarization of society requires that we end the present student debt system.

Third, it depends on whether the education and knowledge student loans are intended to pay for ought be commodities in the first place. This is where Plato enters again. Plato held a life-long antipathy to “sophists.” This word had a sociological reference–those who sell their knowledge to students—as well an epistemological one—those who claim to be wise. The sophists believed that knowledge was a commodity that could be exchanged for money. This was their answer to the question that has been at the center of the debate concerning the development of “for-profit” universities and the intensification of corporate efforts to impose intellectual property legal regimes on academic labor. Plato would not approve. His was a notion of knowledge that was neither commodified nor commodifiable. In Plato’s Republic those who know are to live a perfectly communistic life, neither paying for their education nor getting paid for its use. For two thousand years this conception of an academic institution remained the dominant one, and even in these neoliberal times it still has value.

The very status of most universities (that are either public or private but non-profit) and the traditional temporal limitations placed on “intellectual property rights” (e.g., patents give monopoly rights for the sale of an invention for 20 year) indicate that, despite highly organized and well-financed efforts, the commodification of education and knowledge is still not perceived as legitimate. If most universities are not supposed to profit from the education they provide and the knowledge they disseminate, why should ancillary financial institutions profit from them instead?

Student debt refusal, then, is in principle as just as one’s refusal to return a borrowed loaded gun to a maddened friend who intends to murder and then commit suicide with it. It should not be deterred by objections like the following, “Wouldn’t canceling all student loan debt be unfair to all those people who struggled to pay back their student loans?” For as David Graeber retorted in his important book, Debt: The First 5000 Years, this argument is as foolish as saying that it is unfair to a mugging victim that his/her neighbors were not mugged as well! (p. 389) Plato would agree.

Look for Part 2 of Report From Greece by George Caffentzis — with Silvia Federici — here.

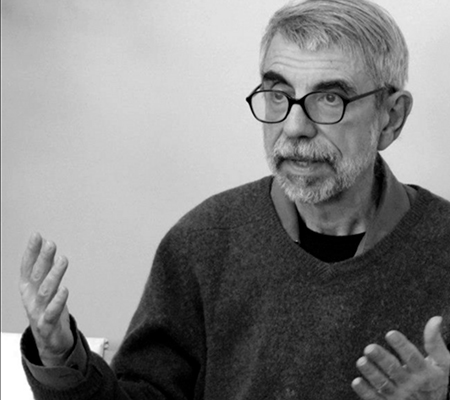

George Caffentzis is a philosopher of money. He is also co-founder of the Midnight Notes Collective and the Committee for Academic Freedom in Africa. He has taught and lectured in colleges and universities throughout the world and his work has been translated into many languages. His books include: Clipped Coins, Abused Words and Civil Government: John Locke’s Philosophy of Money, Exciting the Industry of Mankind: George Berkeley’s Philosophy of Money; No Blood for Oil! and In Letters of Blood and Fire: Work, Machines and the Crisis of Capitalism. His co-edited books include: Midnight Oil: Work Energy War 1973-1992.