By Alan King

alanwking.wordpress.com

August 7th, 2011

Walking past DC’s Watts Park in Northeast, the people stopped in their tracks when they heard Mister Señor Love Daddy, from Spike Lee’s Do The Right Thing, speaking.

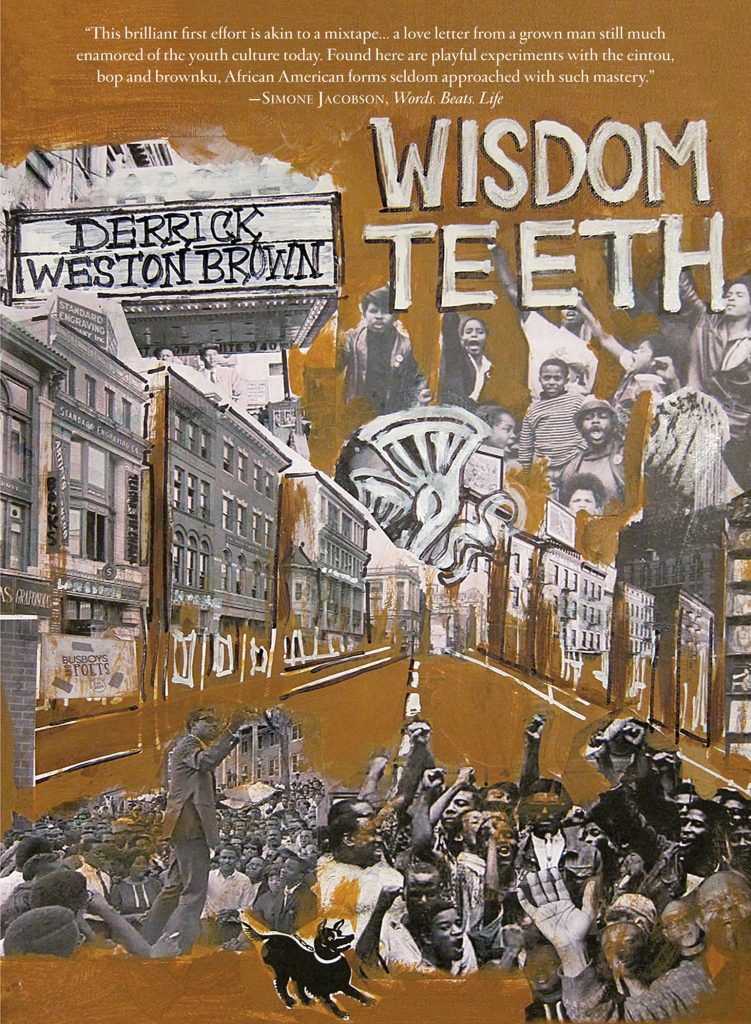

The fictitious disc jockey was invoked through a poem by Fresno, Texas-poet Jonathan Moody. Through Derrick Weston Brown’s reading of the poem, Love Daddy held court for three minutes, long enough to lend his voice to an issue of concern not just for the folks on foot, but those driving by, who pulled over to get the 411.

“My people, my people,” he said. “What can I say; say what I can.” And just as baffled as the character and Brown himself were other poets and organizers who took over the park’s Marvin Gaye amphitheater August 6 to do something about the ill-equipped DC public schools’ libraries.

“It seems the politics of this city are costing our children their right to a quality education,” Melanie Henderson, an organizer for Saturday’s event and managing editor of the literary journal Tidal Basin Review, said in an interview afterwards.

“It is unimaginable what the effect on a child’s self-esteem might be when walking into a nearly-empty school library,” Henderson said.

The last straw for many was the Jan. 23, Washington Post article on Ballou Senior High’s poorly-stocked library. “The literature section of [school librarian] Melissa Jackson’s library…had 63 books one morning last week, not enough to fill five small shelves,” Post Reporter Bill Turque wrote in his article “Librarian at D.C.’s Ballou High Scrambles for Books.”

“In the area marked ‘pure science,’ there were 77 volumes,” he continued. “This is not because the students at the Southeast Washington school had scoured the stacks and checked almost everything out. Ballou’s entire collection consists of 1,185 books, about one per kid.”

And that’s just at one school. Poet and public interest lawyer Brian Gilmore described the public school library system as horrific. “The DC Public School libraries I have seen resemble a library I once saw at Lorton Prison when I taught there in the 1990′s,” he said. “Few books, hardly any good books of any relevance, and the books are ragged, old and insulting.”

“And,” in the words of Mister Señor Love Daddy, “that’s the double-truth, Ruth.”

Henderson and others at this past Saturday’s Summer 2011 Literary Arts in The Park wondered how the historic traditional public schools in the nation’s capital were below the 100 book per student threshold. “Our kids here deserve not just enough, but the best,” Henderson said.

Another point of contention were the current disparities in educational resources between the city’s haves and have-nots. “I have also seen libraries at private schools in the area and these libraries are usually stellar,” Gilmore said.

Among those private schools with stellar libraries is Sidwell Friends School, where Sasha and Malia Obama are among the 1,109 students.

In a post on her award-winning website, author and freelance writer Susan Ohanian noted that the school has three libraries. “The Upper Level school library contains over 20,000 volumes,” wrote the former educator and current fellow at both the Education and the Public Interest Center at the University of Colorado-Boulder and the Education Policy Studies Laboratory at Arizona State University.

Ohanian noted that Sidwell Friends has a separate area for books about the study of China, adding that students also have access to more than 50 magazines and journals. “The library also subscribes to ProQuest for online periodicals in full text,” she wrote. “This service is available both at the school and to students when off-campus.”

Ohanian sent out a charge for the First Family to correct the disparities. “I know there are thousands of schools across the country hurting for the lack of books, libraries, and librarians, but when we see one little light of a school trying to buck the anti-library tide, we must try to help,” she wrote. “And we should urge our First Family to do likewise.”

The poets and organizers at the Saturday event at Watts Park responded to a similar call to action sent out by Tidal Basin Review, Marshall Heights Community Development Organization, and Ward 7 Council member Yvette M. Alexander.

Abdul Ali shared a poem about his experiences at a creative writing workshop at Howard University.

The event kicked off a series of book drives to take place around the city to help benefit DC Public School libraries.

Gilmore, who was on the program to perform but didn’t make it because of a last minute scheduling conflict, did collect books for the drive. Though there in spirit, he called Saturday’s event a shift in approach to the educational shortcomings of a community attempting to take back control of education for city youths.

“Instead of complaining about a broken school system that is not designed to work for children of color, and never was, this is a grassroots effort to fill in a much-needed gap,” Gilmore said. “It also…sends a message to the children that someone really does care and you are not just a number on a ‘No Child Left Behind’ report.”

But more needs to be done, Gilmore noted. He suggested the organizers creating a grassroots coalition or a nonprofit to work outside what he calls “the toxic dysfunctional government apparatus.” This coalition or nonprofit would regularly collect and make literature available to DC public school libraries.

Saturday’s event was just the initial effort, Gilmore noted, applauding the organizers for “a small, yet, symbolical way” of showing DC youths they’re not alone.

Henderson agreed. “Events like these empower average people to cause change in their own and in the communities of others,” she said. “It puts the power back into the hands of the people, whose love and connection to a place or space will push them to work harder and give more to the positive development and preservation of the culture, or cultures, that have nourished them.”

Henderson hoped residents left inspired to affect change in their own ways. She also hoped the event would spur “wider and stronger community involvement in support of youth.” Like Gilmore, Henderson offered suggestions on how to take the next step.

“This is a problem with a practical solution that everyone can be a part of and feel good about,” Henderson said. “The idea is to take what you know, your own talents and gifts, and your resources and networks and use them to better your community.”

During the event, the poets took the stage after posing for a group photo with organizers and Ward 7 Council member Yvette M. Alexander.

Among them was Abdul Ali, who jumped at the opportunity to be part of the effort. “I liked the idea of sharing poems with a book drive,” Ali said. “It’s a rare opportunity to do literary activism and a reading all in one.”

Poet Yao Hoke Glover agreed with Ali. “Literacy and the promotion of reading is the foundation of a community’s ability to transfer ideas [and] connect with one another,” Glover said. “The concept of books and literature must be cultivated in the children at an early age.”

That the event took place in Ward 7, with construction on the new Woodson High School in the background, made it all the more symbolic for the poet. “I would hope the event is a very concentrated and solid beginning to the strengthening of D.C. Literary Culture, particularly in the African American Community,” said Glover, who closed out the reading with poems about his father.

The highlight of the event was Mister Señor Love Daddy’s appearance on that humid Saturday. “Yes, children, this is the cool-out corner,” the fictitious disc jockey said in a poem written by Jonathan Moody and performed by Derrick Weston Brown, who opened up his set with OPP (Other People’s Poetry) before reading his own.

The character’s words summed up the mood of those gathered that afternoon in the park. He said, “I’ll be giving you all the help you need.”

For those interested in donating books, please contact Melanie Henderson via email at [email protected].