By Jay O’Hara

Waging Nonviolence

May 16th, 2017

To the outward eye, the climate movement looks to be back on its heels, reeling from the ascendancy of a fossil fuel regime, the completion of the Dakota Access Pipeline, the zombie Keystone XL and the threatened departure of the United States from the Paris Climate Accord. And there’s not much I can offer, as a climate organizer, to dissuade one from that opinion. The one major effort thus far was a massive march on Washington, D.C. that was planned when most expected Hillary Clinton to be in the White House. So we’re left wondering: What the hell are we supposed to do now?

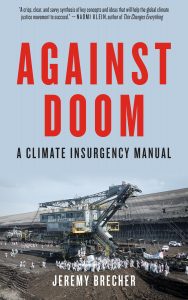

Into this breach steps Jeremy Brecher’s slim new volume “Against Doom: A Climate Insurgency Manual.” Neither glitzy, eloquent nor subtle, Brecher methodically lays out an interlocking vision of direct action within a constitutional legal framework to build the powerful nonviolent climate insurgency necessary to turn the ship around. “Against Doom”smartly connects disparate threads of the existing climate movement and pulls them together with strategic vision. I finished the book fired up with a clearer sense of where my own work with the Climate Disobedience Center, as well as my Quaker faith community, fits into an unfolding climate insurgency. And I’m ready to get back to the pipeline valves, coal piles, construction sites, boardrooms and courtrooms where we have the opportunity to stem the tide of climate cataclysm.

Brecher puts all this in perspective right up front: Before Trump, the Paris agreements represented merely “the illusion that world leaders were fixing climate change” — with ineffectual emissions reduction targets of only 2 degrees Celsius (non-binding) and 1.5 degrees (aspirational). As such, Trump is only a refreshingly honest manifestation of the movement’s failure to muster sufficient power to achieve its ultimate aims. The illusion of the efficacy of an inside politics game somehow survived the failure of cap-and-trade among the major environmental groups, and those groups refocused on the Obama administration’s potential for executive action. At the same time, the national fight against Keystone XL and grassroots resistance by frontline communities across the country and globe have laid the groundwork for a strategy of insurgency.

Insurgency

The strength of “Against Doom” lies in getting to the next layer of strategic sophistication about what a plausible insurgency strategy looks like. While many activists may say that “increasing the negative consequences of continuing fossil fuel extraction and burning” is the aim of their tactics, Brecher starts in a very different place. He argues that “The most important targets of the climate insurgency are the hearts and minds of our friends and neighbors locally, globally and virtually. The goal is to encourage them to organize themselves and act to protect the climate.”

Brecher makes the implicit case for a movement of nonviolence by putting “costing the fossil fuel industry money” fifth on his list of eight ways to build climate insurgency. He argues that a “by any means necessary” approach to shutting down fossil fuel infrastructure will alienate rather than encourage the participation of those we need. The first fight we have to win is the fight to get the rest of the troops off the couch: to activate and mobilize those who say they agree with us, but are — as of yet — unmoved to take action. Implicitly, he argues that maintaining nonviolent discipline is necessary to unlocking the potential power of our soft supporters. Several times in the book, Brecher musters a slew of public polling data to say that support for dramatic climate action is broad, but weak. Therefore, it isn’t hard to extrapolate from that data the kinds of actions — like a covert campaign of industrial sabotage — that would send those soft supporters running to embrace the status quo. Instead, they need to bring the fight to their churches, unions, governments and other institutions that form the “pillars of support” for the fossil fuel industry. In that sense, Brecher is making the case for an insurgency that is transparent and inviting.

Brecher also gets the insurgency’s objective right, which is to motivate anyone with some piece of the fossil fuel lever in their hands to make policies and choices that meet the admittedly high bar of averting cataclysm. This is where we can draw the most distinct line between what is establishment environmentalism and climate insurgency. For nearly a decade, environmentalists have mistakenly focused on passing a cap-and-trade bill, regardless of whether it met the objectives of sufficiently reducing emissions. Signing a global treaty became the goal, rather than getting commitments to emissions reductions that would limit warming to below 1.5 degrees Celsius.

Both of these events saw the environmental establishment laud policymakers and negotiators for their great accomplishments. Most recently, the League of Conservation Voters endorsed Hillary Clinton, the pro-fracking presidential candidate, and gave Bernie Sanders a 6 percent score on their annual report card — despite the fact that he was running a campaign committed that took science seriously and declared climate to be our most serious national security threat. The existing climate movement isn’t immune to this tendency either, as it is constantly confronted with people who want to be positive and focus on solutions. As a means to confront this issue, Brecher insists that “it is not the role of the climate insurgency to determine in detail the specific pathway institutions will take to eliminate fossil fuels.” That is something many different groups — both “inside and outside the climate insurgency” — need to figure out. “The role of the climate insurgency,” Brecher writes, “is to make clear the negative consequences — from climate change and from movement action — that will befall those who do not take such measures.”

Public trust

This isn’t an insurgency of law breaking, however. It is a campaign of law enforcing, and Brecher nests the climate insurgency inside a developing legal and constitutional framework developed by author and law professor Mary Wood. In her remarkable book “Nature’s Trust,” Wood has provided the world, the courts and our movement with a powerful legal understanding of the inherent rights of all of humanity to have a livable, stable climate.

Brecher gives ample space to describe the ongoing Our Children’s Trust litigation, in which youth from around the country are suing federal and state governments for their right to a livable planet and the imposition of a reasonable climate action plan. These lawsuits represent one of the insurgency’s early manifestations, and they aren’t acting in isolation from the rest of the climate movement. Instead, their action is part of a necessary and powerful strategy towards fueling climate insurgency. Every instance of a legitimation of the insurgency, and a de-legitimation of the fossil fuel paradigm, strengthens the soft middle to be in support of climate action.

As with our efforts at the Climate Disobedience Center to win a climate necessity case in front of a jury, public legal battles, like Our Children’s Trust, make the claim that civil disobedience actions are legally justified and support the broadening of the insurgency beyond the choir. Climate direct action — in this view — isn’t law breaking, but rather law enforcing.

Where we go from here

The insurgency is, of course, already underway. The question is: How do we move from a niche movement to a broad-based insurgency that encourages people who agree with us — but haven’t taken action — into places of bold risk-taking?

“Against Doom” doesn’t limit its vision of action to civil disobedience and physical infrastructure disruption. Instead, it sketches a totalizing vision, where ordinary people enforce a fossil fuel freeze and force the adoption of climate action plans within their spheres of influence: their church, town, union, business or workplace.

Brecher wisely eschews the temptation to list all of the things that people are doing or could be doing to bring this about. In its place he emphasizes two principles necessary to fostering a mass movement: self-organization and de-isolation. Both the book and the movement would benefit tremendously from a deeper exploration of these concepts. De-isolation — which is premised on an understanding that climate grief and despair are generally privately held angst rather than a publicly-connecting political frame — necessitates the deep connecting of individuals who share a “climate wake up call.” Creating deep bonds of trust in place of isolated individual worrying is the necessary stepping stone into self-organization.

Self-organization, of course, is necessary if the climate movement is going to break out and go mainstream. An NGO-led, top-down model of organizing is wholly insufficient when it comes to creating the exponential increase in mobilization and power that’s needed in the limited time remaining. This isn’t to say that grassroots resistance to fossil fuels and climate injustice isn’t organically popping up across the country — it most definitely is happening. But it is curious that Brecher’s best example of how this is supposed to work are the global actions that took place last May as part of the Break Free from Fossil Fuels campaign.

As a member of the organizing team for Break Free Northeast in Albany, New York, I can say that we intended Break Free to be the beginning of something new in the climate movement: mass civil resistance coordinated across the United States and around the globe. It was the product of a lot of self-organization, paired with a national and global movement connection that made the whole more than the sum of it’s parts. It took thousands of people who had never engaged in climate disobedience and guided them to a path of deeper commitment.

But did the participants move deeper into a sense of their own power to drive forward a climate insurgency? At Albany’s Break Free action, I think we failed to create the sort of training and gathering that would lead to de-isolation and self-organizing. This was mainly due to tight centralized control in the organizing committee, over emphasis on a one-to-many communication style in a rally atmosphere, and training that was too brief and tactical, rather than relational. We’re going to have to work harder to help participants build the sort of deep relationships with others who show up and could go on to self-organize insurgency campaigns in their own neck of the woods.

Much of our movement has assumed that skills and tactical knowledge, paired with an organizational structure, are sufficient to create the power we need. In Albany, we lost the opportunity to help form and strengthen the bonds of trust among the mass of people who gathered, and thereby failed to model and teach empowered self-organizing models like affinity groups.

While the path from sporadic grassroots rebellion to full blown insurgency is not spelled out in detail, Jeremy Brecher’s “Against Doom”is an invaluable strategy manual that provides a framework for all of us to reflect on our role in building a climate insurgency. With the values and principles he lays out, our diverse and experimental movement should be able to see our work connect to a larger project in a way that emboldens and strengthens. He has laid out the “what,” but left it to us to fill in the “how.” Let’s read it and get back to work.