By Dan Berger

Truthout

October 14th, 2015

The underground is an elaborate metaphor for the many subterranean ways of living, thinking and feeling that percolate our movements. (Photo: Glen DeWitt)

Changing the world is hard. Activism contains so many unknowns, and so many difficult decisions with impacts we might guess but can only know in retrospect. The combination of urgency and despair, strategy and principle, has fueled many efforts at radical transformation. Ultimately, we give it our best shot and hope that it makes a difference. One of the hardest things, then, is learning to live with loss. How do we keep fighting after something – an approach, an organization – we poured our hearts into has fallen apart? How do we act reflexively and across political generations or perspectives?

These are difficult questions. But in the absence of the dramatic social change we pursue, grappling with such problems trumps giving in to apathy or rejecting the need for change. It is, in fact, an opportunity to live a political life committed enough to grapple with these issues. Radicals of all stripes ought to confront and reflect upon these issues. But they continue to circulate around those who have gone underground.

The underground is an elaborate metaphor for the many subterranean ways of living, thinking and feeling that percolate our movements.

Of all such strategies, perhaps no decision is as fraught – as controversial and yet, as I have explored elsewhere, misunderstood – as the one to go underground. It has been taken up in novels, memoirs, history books, plays, documentaries and Hollywood cinema. Part of the fascination may lie in the fact that an underground is hard to imagine in these days of permanent surveillance and social media overexposure. Yet the best of these cultural texts show that the underground is an elaborate metaphor for the many subterranean ways of living, thinking and feeling that percolate our movements.

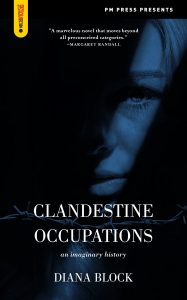

Certainly that is how writer and activist Diana Block conceptualizes the underground in her new novel. Clandestine Occupations is a nuanced and intimate portrayal of radical activism’s far-reaching consequences. The book takes place across four decades and six narrators, each one relating to a revolutionary named Luba Gold. Each chapter is told through a different narrator. We meet Luba in 1986 through the eyes of Belinda, her coworker. We follow her through Joan, a friend who ultimately betrays her to the FBI; Sage, a former friend distanced by the intensity of their radical group; Maggie, who meets Luba in 2007 when they both support the parole attempt of someone in prison; and Anise, the daughter of Sage and a budding young activist. Luba herself has the last word as she narrates the last chapter, set in 2020 when a new underground is on the rise.

Clandestine Occupations is in some ways a sequel to Block’s beautiful 2009 memoir, Arm the Spirit. More accurately, it is a retelling. Both books find the protagonist plotting to free a Puerto Rican political prisoner, fleeing an FBI sting in Los Angeles with an infant in tow, living underground for 10 years in Pittsburgh and returning to public activism in San Francisco. After returning from living underground Gold, like Block, cofounds an organization focused on supporting and freeing women in prison (Unshackled Women in the book, California Coalition for Women Prisoners in real life).

Other characters mirror real people as well. Cassandra, a political prisoner caught up in the sting Luba narrowly escaped and who was unexpectedly placed in isolation after the 9/11 attacks, bears many resemblances to Marilyn Buck, a white ally to the Black Liberation Army who spent more than 25 years in prison – including being held incommunicado after 9/11 – and who died three weeks after being granted compassionate release. (The same fate befalls Cassandra, too.)

Another political prisoner central to the book’s story arc is Rahim, a former Black Panther who is reconnected with many of his California comrades when he is sent across the country to stand trial on a specious 30-year-old case. He resembles Jalil Muntaqim, also a former Black Panther who has served more than 40 years in prison and was one of eight Black Panthers charged in 2007 with the 1971 death of a San Francisco police officer. One suspects that other characters in the book are also drawn from people in Block’s experience. The book’s subtitle rings true when it proclaims itself “an imaginary history.” A series of real-life events, from the 1970 Venceremos Brigade trips to Cuba to today’s Black Lives Matter movement, propel the book’s story arc.

Block casts parenthood and revolutionary commitment in a global context rare for many American discussions of child-raising.

While both books share the same scaffolding, they are different texts. Arm the Spirit traced Block’s evolution as an activist into anti-imperialist feminism, her work against state repression and sexual violence, her decision to go underground in support of the Puerto Rican independence movement while parenting a newborn and her rebuilding of a public activist life upon returning from the underground. It is a tender and vivid book, simultaneously chronicling a previously unexplored aspect of recent left-wing history and voicing the complexity of finding oneself doing two very difficult things at the same time, living underground and raising a child (ultimately, two children). In Arm the Spirit, Block renders her decision to be a parent alongside her decision to go underground in a compelling, humane fashion. She noted that revolutionaries around the world become parents in difficult circumstances, including more difficult ones than hers. She casts both parenthood and revolutionary commitment in a global context rare for many American discussions of child-raising.

Clandestine Occupations incorporates parenthood into clandestinity – Luba also decides to have a child around the time of going underground. But the book’s greatest success is in its powerful rendering of the commitments and fragilities of this interconnected group of radicals and associates. In fact, many of the most sensitive portraits are of people leaving the radical left, at least in terms of everyday activism: Joan betrays the underground at the suggestion of her creepy boyfriend, who later turns out to be an FBI informant. Sage chooses her personal relationships over her political activism, especially after the rigidity of the “Uprising” organization (modeled loosely after the Prairie Fire Organizing Committee, of which Block was a member in the late 1970s) leaves her few options.

The book beautifully, painfully illustrates the dangers of dogma and ego. It also shows the severity of clandestine politics. Whereas Arm the Spirit chronicled Block’s journey underground, Clandestine Occupations takes up subterranean politics from the perspectives of those left behind. It is a powerful way to tell the story of the underground, depicting the pain of not being able to account for one’s comrades and loved ones. It puts the emphasis on social relationships rather than spy-movie tricks. And the resulting picture is complicated. Belinda is Luba’s coworker, a fairly apolitical and lesbian (largely closeted – her own clandestine operation) nurse, who the FBI tries to pressure into cooperation once Luba flees. She resists the FBI and finds a bit of political independence in her courage. Sage, meanwhile, is isolated from her work after she decides not to go underground and has told her daughter little about her past. Sage’s reluctance to share information about her past distances her from her daughter, who has to find her own way in the world. Anise’s search for discovery and political purpose leads her to visit political prisoners, participate in Occupy Wall Street and take part in an underground adventure of her own.

Telling the story of the underground through other people’s experience of it – including Luba, who meditates on the rise of a new, more tech-based underground in the year 2020 – is a compelling approach. It gets at what is compellingly vexing about clandestinity: It is elliptical, unknown, simultaneously enticing and elusive. That holds equally true for the clandestine space that some radicals find themselves in: prison. Block captures the emotional range of visiting or corresponding with prisoners, the running dialogue between hope and despair, as well as the pathos of supporting people through decades of confinement. “This much I remembered – prison visits cooked emotions until they threatened to boil over in a sizzling, uncontrollable mess,” Sage confides of her experience visiting Rahim in prison after more than two decades of silence.

Clandestine Occupations has its own elusions. It is not clear, for instance, why Luba’s group wanted to break that specific (unnamed) woman out of prison, or what she would do once freed. The purpose of going underground and its possible connection to aboveground activism is not well explored here. Block also utilizes some jargon of the far left – for instance, she refers to politically motivated bank robberies as “expropriations” – and does not provide much background of the social movements involved. The uninitiated reader may stumble over some of the references or miss the nuances at times assumed here.

Still, Clandestine Occupations provides a powerful, deliberately fragmented glimpse into political commitment and accountability. There are some lovely passages here about retaining commitment while aging. There are the small-scale recognitions of the struggle continuing, such as when Luba and Sage run into each other at a 2003 demonstration against the Iraq war, “glad … to be on the streets together again, now with our children, bracing for the slaughter to come.”

The most powerful examples concern deep personal and political reckoning. Joan, who betrays Luba at the behest of her FBI-informant boyfriend, is a sympathetic figure troubled by her decision from decades earlier. She writes a letter to apologize for her betrayals, which seems to provide a shaky comfort to some of the book’s characters. One wishes that Block, a strong and evocative writer, had included the text of Joan’s letter, not only because of its impact on the characters but to see Block’s imagination of how – especially in the context of growing state surveillance – fractured political bonds could be rebuilt through honest, vulnerable dialogue.

Betrayed by Joan, Luba and Cassandra also need to reckon with their own egotism in the context of intergenerational activism. Each woman grapples with Anise’s youthful intemperance and sense of urgency. Luba finds herself shocked at Anise’s decision to go underground as part of a hacker-led effort to stifle electronic surveillance in Palestine and the United States, in an effort that sparks the “Urban Maroon” movement to shield formerly incarcerated people from state violence. It is a satisfying end, to show that state violence will continue to generate clandestine forms of organization, even as they shift from one generation to the next.

Ultimately, Clandestine Occupations is a poignant reminder of the reverberations of radical activism. In a revealing passage, Luba writes of the collective responsibility all must bear in social movements. “We had been so full of our righteous rage, our correct political convictions, our determination to push ourselves and others to the limits of militancy that we excluded those who wanted a different role,” she writes. “We failed to see how our harshness, our superior standards, our cliquishness could drive people into the arms of our enemies.” Luba’s self-reflection comes in 2020, after decades of organizing and intense political commitment. It is a warning borne of experience, from the future as much as the past, to build movements that are uncompromising in their vision but capacious in their empathy.