By Jake Slovis

H-Socialisms

December 2016

Punk and Politics

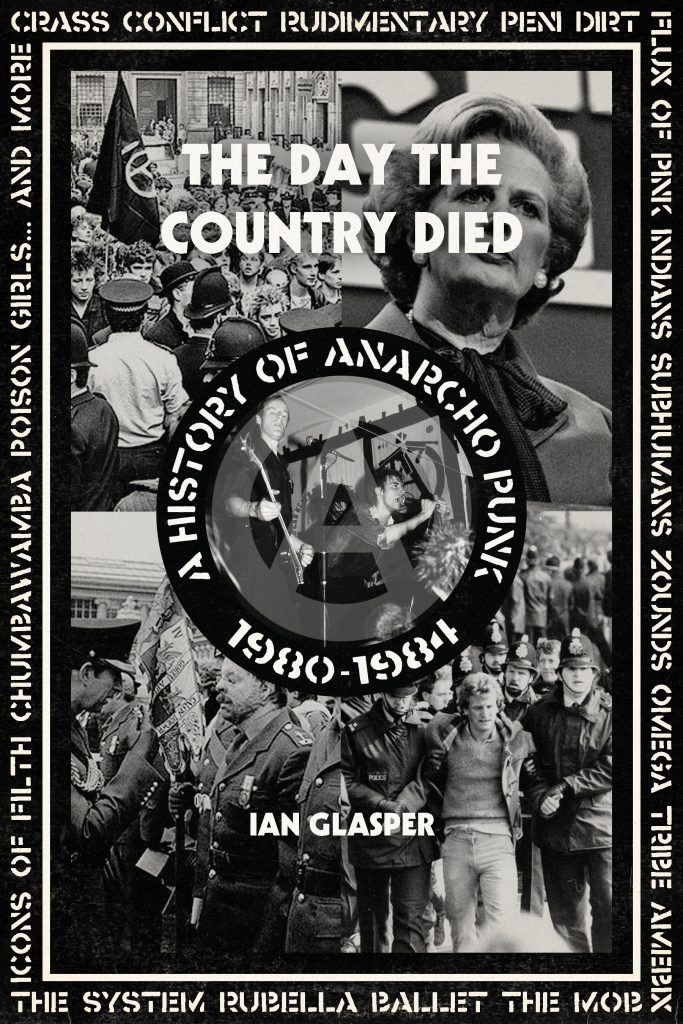

In The Day the Country Died: A History of Anarcho Punk, 1980-1984, Ian Glasper tracks the formation and growth of the anarcho punk scene in the United Kingdom. According to Glasper, the time span the book covers is significant because it marks the period in which anarcho punk evolved from “an outlandish fashion statement” to a political subculture “yearning for internal and external peace and freedom” (p. 8). This loose description helps Glasper to separate the “anarchy and peace” punks from the “anarchy and chaos” punks documented in his Burning Britain: The History of U.K. Punk, 1980-1984 (2014). Glasper is likewise deliberate to define anarcho punk in abstract terms, as the movement prioritized ethics over the “rigid musical doctrines” that came to define other brands of punk (p. 9).

One of the successes of The Day the Country Died is that Glasper cites influential figures in the anarcho punk scene without elevating these figures above the movement itself. This helps to highlight the inclusionary politics of anarcho punk, which actively worked to disassemble “divisions between audience and band” (p. 50). It is therefore with some reluctance that Glasper credits the band Crass as one of the “leaders” of the anarcho punk movement. However, there is no denying Crass’s influence, as they were one of the first to combat the commercialism exhibited by punk acts in the late 1970s. According to drummer Penny Rimbaud, “‘commercial punk was a complete sham, part of the rock‘n’roll circus, operating in the same way as someone like Marc Bolan [from T. Rex]—which is not to denigrate it as such … after all, music is an industry; it produces product and people enjoy product.’” For Crass, the attachment of music to “product” cheapened the anti-establishment ethos that they believed punk could embody. Crass therefore saw the need to pursue activism in more explicit and tangible terms. Glasper writes, “they [Crass] weren’t interested in sensationalist unworkable notions of anarchy and chaos, they wanted a gradual revolution from within” (p. 11). In this way, Crass differed from iconic bands like the Sex Pistols, who only “hinted” at rebellion. Instead, Crass favored direct action, which gave “shape and purpose” to the anarcho punk movement.

Glasper also cites Flux of Pink Indians as one of the more influential anarcho punk acts. Like Crass, Flux of Pink Indians avoided characterizing themselves as “leaders” within the anarcho punk community. However, unlike Crass, Flux of Pink Indians cultivated their political priorities as they developed, originally forming with “ambitions no loftier than making a bloody racket for the sheer hell of it” (p. 32). It was through touring and observing the rise of Thatcherism that Flux of Pink Indians turned toward activism. By the end of their tenure, the band not only took on an anticapitalist agenda but also embraced vegetarianism as part of their ethical code. Glasper writes that their “Neu Smell” EP (Extended Play) was “probably responsible for more punk rockers turning vegetarian than any other” (p. 32).

Outside of Crass and Flux of Pink Indians, members of Conflict, Subhumans, and Lack of Knowledge contribute lengthy oral testimonies to The Day the Country Died. The result is a documentary style narrative that privileges experience over any other form of evidence. This choice is both a success and failure. While relying on testimony underscores the collectivist ideals of anarcho punk, the length of the testimonies are overbearing at times. Furthermore, it absolves Glasper of being the primary storyteller, as the testimonies are surrounded by little analysis and it is often unclear as to how they fit into a larger framework.

Structurally, the book is divided into chapters based on the regional affiliation of the bands discussed. This allows Glasper to show that while anarcho punk was widespread in the United Kingdom, it relied on local engagement in order to develop. Throughout The Day the Country Died, performers often cite experiences with other local activists, exposing an intimacy within the scene. According to Lack of Knowledge vocalist, Daniel Drummond, “‘being a part of it [anarcho punk] was more important than just watching bands’” (p. 50). Many other bands echo Drummond’s sentiments, demonstrating a serious interest in communalism and group participation. This is not to say that anarcho punk’s political priorities were limited to communalism. Bands like Conflict fully tested anarcho punk’s “no rules” mantra, as they “militantly” defended animal rights. Others advocated for sexual equality and many worked to challenge Margaret Thatcher’s reforms. This challenge is perhaps best characterized by the band Thatcher on Acid, who formed “chiefly as a name” and were primarily motivated by ideals of “freedom and co-operation” under fears of nuclear war (p. 221).

However, like many bands motivated by the movement of the early 1980s, Thatcher on Acid felt disillusioned by the scene as it began to change by the late 1980s and early 1990s. Guitarist Ben Corrigan says, “‘we felt that, even though there were an awful lot of bands and people involved within it, the scene itself was fragmented, permeated with a kind of inverted snobbery and was actually largely fake’” (p. 223). Corrigan also expresses concern that the scene seemed less about direct action and more about occupying an anti-this, anti-that position without clear purpose. Glasper does not fully clarify whether this change came as a result of the rapid growth of anarcho punk without a unified vision or as a result of the commercial success of anarcho acts like Chumbawamba. What is clear is that as anarcho punk became more prevalent, the effectiveness and intimacy of the movement was compromised.

Glasper concludes by dubbing anarcho punk “the most real and challenging incarnation of punk rock ever seen or heard.” That anarcho punk was something to be “seen” as well as “heard” does much to underscore that the movement was more than a sound; it was an experience and feeling. It is for this reason that nostalgia is often frowned upon, as so much of the movement was contingent on “doing.” Glasper also emphasizes that while the feelings that motivated anarcho punks were “stimulated” by the time, the spirit of the movement “remains an indomitable constant as long as there is injustice in the world” (p. 456). This “spirit” is perhaps best clarified by Scott Paton, guitarist of AOA: “‘We decided to vent our anger through music, and take a more direct approach with our protest, and for the most part it had the desired effect: an all out attack on what we wanted to change. And now here we are again; the relentless cycle of life and death continues unabated. There will always be something to be angry about … and always a corresponding need for change’” (p. 455). While anarcho punk has faded, AOA’s message functions as a rally cry for future activists. It is founded on the hope that there is always an opportunity for change and suggests that anarcho punk’s ethical foundation will continue to endure within the social justice movements of tomorrow.

Printable Version: http://www.h-net.org/reviews/showpdf.php?id=45917

Citation: Jake Slovis. Review of Glasper, Ian, The Day the Country Died: A History of Anarcho Punk, 1980-1984. H-Socialisms, H-Net Reviews. December, 2016. URL: http://www.h-net.org/reviews/showrev.php?id=45917