By Seth Sandronsky

Z Communications

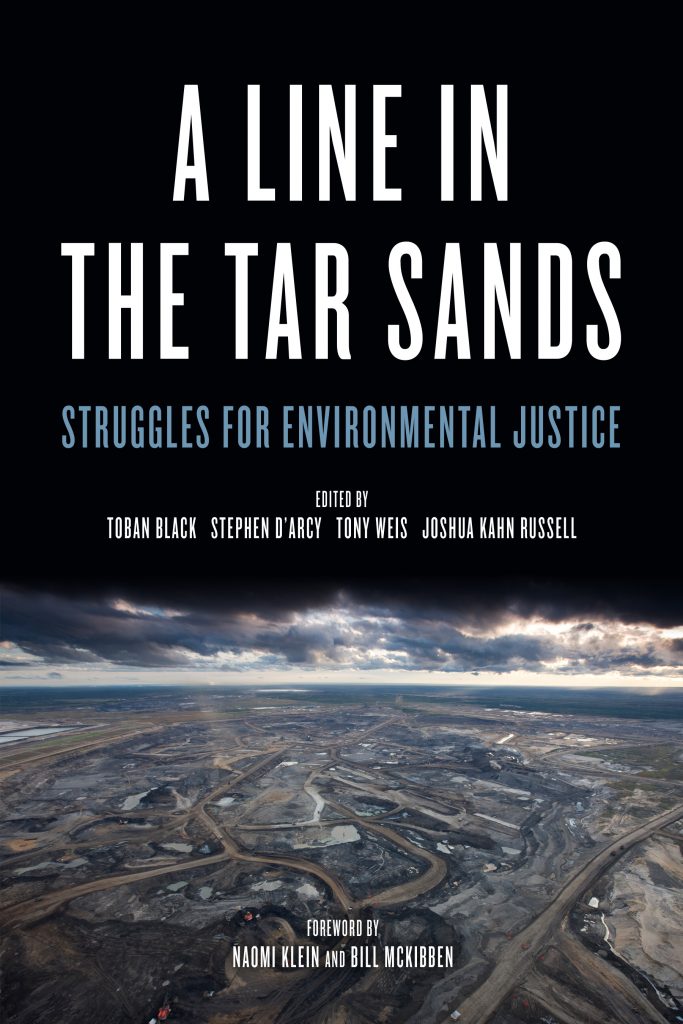

Most contributors to A Line in the Tar Sands: Struggles for Environmental Justice (PM Press, 2014) are indigenous women. They bear witness to Trans- Canada’s bid to mine more carbon-heavy and planet-warming bitumen from tar sands in Northern Alberta, Canada (due north of Washington state). This is a toxic strip mine the size of Florida, prized for its energy goo, extracted with natural gas (to power machines) and water from clay and sand below the earth.

A foreword by Naomi Klein and Bill McKibben sets the stage, thematically, for the book’s three parts. First is the politics of the tar sands development: what they are, and why this epic battle is raging. Second is the communities, i.e., Lubicon Cree First Nation and Beaver Lake Cree Nation, resisting such energy development in Canada. Part three covers the prospects for enhancing the movements for climate justice.

Lethal leaks and spills from tar sands development harm humans, nature and wildlife. Tar sands extraction, distribution and consumption is a recipe for a “climate bomb,” according to NASA scientist James Hansen. That bombing will cook the planet, propelling humanity past a tipping point of runaway climate change. Thus leaving the tar sands in the ground is paramount to climate justice activists.

One contributor is Winona LaDuke, the Ojibwe activist, economist and vice-presidential candidate with Ralph Nader on the Green Party ticket in 1996 and 2000. She joins Melina Laboucan-Massimo and Crystal Lameman. Theirs is a way of life that presents us with a sustainable, anti-capitalist, solution to what TransCanada is delivering. That is tar sands development destroying people and tribes to maintain profit margins and market share.

As the GOP takes control of the House and Senate in January after a low-voter, high-dollar, midterm election last November, the battle against the northern leg of the Keystone XL Pipeline, to transit such dirty energy some 2,000 miles to Gulf Coast refineries for refinement and shipment to China and India is gaining strength. Activists groups mobilizing to prevent this pipeline development write about their efforts, in and out of the courtroom, to prevent damage to the Ogallala Aquifer under the Great Plains, i.e., native lands and farmland.

In this book, we read how groups such as 350.org, in unity with local and global campaigns, are strategizing to disempower the private firms and the public officials upon which Trans-Canada depends. Big Energy has the capital, but its opponents have humanity, to put matters starkly.

Contributors share the process of growing the roots and branches of resistance from ordinary people. What draws them together (think cowboys and Indians) is their lives and livelihoods in harm’s way from tar sands. The past and present relations of these people at-risk suggests that capital is a force to, potentially, unite the masses divided so a few can and do rule. A thread that runs throughout the book is the court of public opinion. The business interests driving tar sands expansion are mobilizing the forces of PR to wage the battle for public consent, employing Edelman, the world’s biggest PR firm. Edelman is leading the charge to “manufacture consent” for TransCanada’s tar sands project.

The Royal Bank of Canada is also driving the ecological nightmare of tar sands extraction and transportation. Joshua Kahn Russell (a Jewish-American, anti-Zionist), global trainings manager at 350.org, and a co-editor of A Line in the Tar Sands, knows about successful strategic campaigns to critique via satire to shape and spotlight RBC’s role. This approach can and does sway public opinion. Echoes of past social movements exist in the present moment. Environmental activist strategies borrow in no small way from the history of the U.S. black freedom movement. Part of this approach features dialogue to identify active and passive supporters and opponents. Know thy ally and enemy alike, indeed. In this way, climate justice proponents effectively advance, Gramsci-like, against corporate interests profiting from ecological destruction.

Greg Albo and Lilian Yap analyze the power and reach of global monopoly finance-capitalism. Their critique of fossil fuels to power capitalist society’s dovetails with the contributions of Angela A. Carter and Randolph Haluza-DeLay. Jeremy Brecher and the Labor Network for Solidarity contribute a vital piece on unions and the environment. Russell’s interview with Harsha Walia casts crucial light on the links among and between migrant labor and tar sands development. Meanwhile, industry PR aims to divide and sub-divide the working class, native and immigrant, setting up a false binary of jobs or the environment. It is if life on a cooked planet heated by the “carbon bomb” of extended tar sands mining is not the ultimate “job-killer.”

Lively trial-and-error informs the active dissent in this timely collection. The ideas and practices of Paulo Freire, the activist Brazilian teacher and writer, loom large. Mapping out a spectrum of allies and foes, following in the footsteps of Bayard Rustin, a civil rights icon, and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, informs the methods of current climate justice activists. Stephen D’Arcy, one of the book’s co-editors, drives this process home in his piece, examining the challenges of asymmetry via identifying “soft spots” in Big Energy, or “secondary targeting” of support institutions, in this case, TransCanada.

In all, moving more people to resist carbon-fuelled climate change to destroy Mother Earth’s clean air, land and water is the book’s direct aim. Theory matters. So does practice. A diverse union of people in solidarity makes the movements to decarbonize the planet grow. This book opens the door to imagining and producing an ecological civilization. Rock on.

Back to Stephen D’Arcy, Tony Weis & Toban Black’s Author Page | Back to Joshua Kahn’s Author Page