Socialist Project

November 10th, 2014

Drawing a Line in the Tar Sands

Of all possible futures, the least likely is one in which business as usual continues unabated. Peoples’ movements will either succeed in transforming our economic and political systems to build a new world, or we will burn with the old one.

Our title invokes a metaphor of uncompromising resistance because the tar sands are an environmental injustice of the highest order. A ‘Line in the Sand’ means: it has gone this far, but no further. We are confronting an industry that is worth trillions of dollars, and is driven by some of the largest corporations on Earth, which have no goals that are any nobler than maximizing short-term profits and growth. The fight to stop this industry is clearly one of the epic challenges of our age, and only serious and sustained mobilization can turn the tide.

The Athabasca River Basin in western Canada contains one of the world’s largest reserves of fossil energy in the form of bitumen, a tar-like substance that must be heavily refined to separate oil from sand and clay – hence the name tar sands.[1] The world’s largest industrial landscape now sits atop the Athabasca tar sands, where the industry is wreaking devastation on the homelands of Cree, Dene, and Métis peoples, immense tracts of boreal forest, and the habitat of many animal species.

The Race to Extend the Age of Fossil Fuels: Profits, Power, and Claims of Inevitability

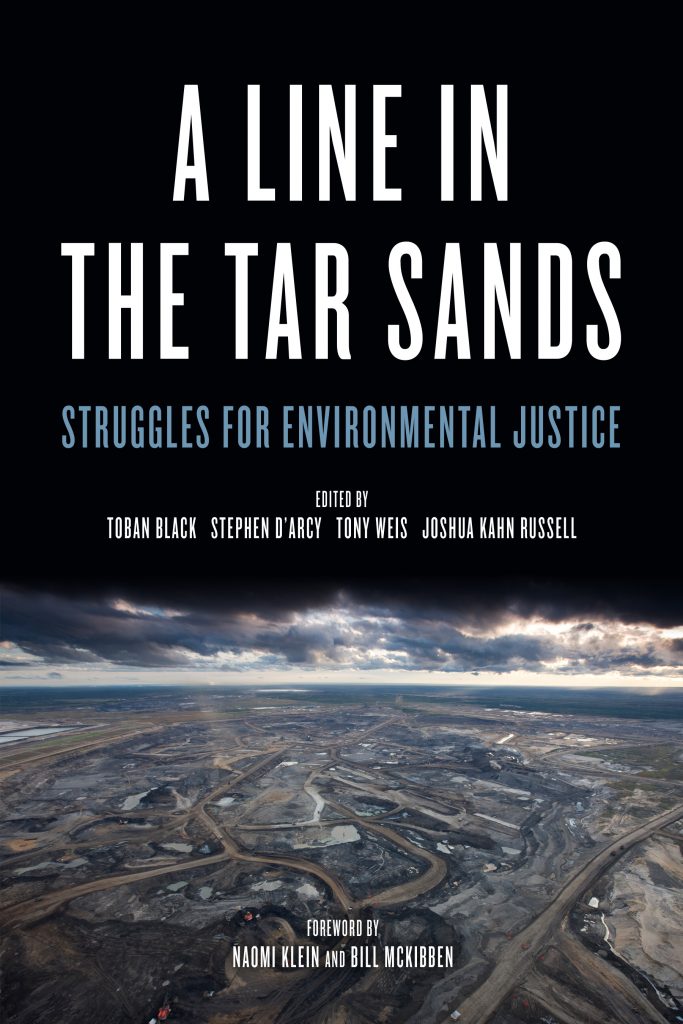

The tar sands landscape is marked by vast deforestation, strip mines, wastewater ‘ponds,’ and freshwater diversions; an expanding network of pipelines and roads; massive refineries and energy generation facilities; and the world’s largest earth-moving machines. In addition to its physical size, the tar sands are regularly identified as the world’s biggest energy project and site of capital investment. In a major 2008 report, Environmental Defence called it simply “the most destructive project on earth.”[2] If this industrial expansion continues across the Athabasca Basin in the coming decades, the tar sands extraction landscape would span an area the size of England.

While the Athabasca River Basin constitutes the heart of the tar sands industry, its infrastructure is increasingly continental in scope. Pipelines are the vital arteries of the industry, bringing bitumen to refineries and ultimately to markets, and they already stretch over thousands of kilometres across North America. At least 50 refineries have been handling blends of tar sands and conventional oil.[3] Still, this is not enough to satisfy investors’ voracious appetite for growing profits, which are driving an aggressive push to expand, construct, or repurpose a series of pipelines in order to increase rising volumes of production and transport.

Several thousand more kilometres of pipelines are planned, including TransCanada’s attempt to expand the Keystone XL pipeline across the U.S. to refineries around the Gulf of Mexico; Enbridge’s efforts to build the Northern Gateway pipeline across British Columbia to enable shipping on the Pacific Ocean; and TransCanada’s plans to establish an Energy East corridor to the eastern seaboard, where Atlantic shipping and refining may occur. The appetite for growth is plainly reflected in the words of Alberta’s finance minister, who claims that the industry soon will require “two or three Enbridge-Keystones” to handle the glut of unprocessed bitumen and continue expanding at the pace sought by investors.[4] At the other end of these pipeline arteries, there is a push for expanded upgrading and refining capacity, port facilities, and ocean-going tankers to widen distribution on a global scale.

This colossal enterprise is driven by a confluence of transnational energy corporations and finance capital. The world’s largest oil and gas companies all have tar sands projects; banks and investment funds from around the world have increasingly joined capital based in Canada and the USA. In addition, the industry has been relentlessly subsidized and promoted by the Canadian and Albertan governments in a range of ways: decades of direct and indirect subsidies; lax regulations and a reliance on “self-regulation”; deep cuts to environmental monitoring capacities;[5] the failure to make serious, multilateral commitments to climate change mitigation; aggressive lobbying in the Canadian press and international policy forums; and missions to lock in trade and investment in the tar sands through bilateral and multilateral agreements.[6] Taken together, it is hard to overstate the magnitude of the economic and political power at hand.

Peak Oil; Peak Consumption

Yet pilot operations began in the late 1960s and the quantity of bitumen in the Athabasca tar sands has long been known, so an obvious question is: why has the industry heated up so much since the 1990s, after decades of far slower expansion? The answer relates in part to the fact that bitumen is much more difficult and costly to extract and refine into usable end products than conventional oil reserves. This means that returns on investment are much lower in the tar sands than in places with cheaper production costs (such as the Middle East, historically), at the same time as enormous capital investment is needed to enable the extraction, transport, and refining of bitumen. So it was not until world oil prices began to rise quickly in the face of growing limits to conventional supplies – reflecting the dynamics of “peak oil”[7] – that the tar sands industry became sufficiently profitable for many large-scale energy and financial corporations to ramp up their investments. Here, it is also helpful to remember that oil, coal, and natural gas account for roughly four-fifths of the world’s net primary energy supply (that is, the sum of energy used in all production, transportation, and households).[8] Of these, oil is the most crucial, as both the greatest source of energy generation and the overwhelming source of liquid fuel that powers global transportation systems. The centrality of oil in global capitalism is reflected in the fact that oil-centred giants, like ExxonMobil, Royal Dutch Shell, BP, Chevron, and Sinopec, consistently rank among the largest and most profitable corporations in the world. The geopolitical dimension of this push is plainly apparent in the Harper government’s attempts to promote Canada as a world “energy superpower,” which is capable of enhancing the “energy security” for its friends, most notably the USA.

It is clear that the race to expand the production of unconventional reserves like bitumen is tied to the decline of conventional oil and gas reserves. In addition to tar sands, this general pressure is also central to the rise of hydraulic fracturing (more commonly known as “fracking”) for “tight” oil and natural gas and mining of kerogen shale (a bitumen-like substance), as well as increasing offshore drilling in deeper water and higher latitudes for conventional reserves.

This overall shift is increasingly being described in terms of a turn toward “extreme fossil energy,” because of the heightened difficulty, costs, risks, and pollution burden it entails.[9] The Athabasca tar sands are the world’s largest “extreme energy” frontier, both because of the size of the area and the scale of bitumen deposits, and because the growth and technological development of the industry there is now helping to stoke the expansion of extraction in similar, though smaller, sorts of reserves around the world, in countries such as Venezuela and the United States.

To hear it from corporate and government elites, this turn toward extreme extraction is more or less inevitable. Their basic argument is that fossil fuels are the lifeblood of modern economies, so further extraction of unconventional reserves in the tar sands and elsewhere is needed to enable continued growth. The basic mantra is that more extraction means more wealth and more jobs. Some industry champions, such as the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers, take the claim of necessity a step further and celebrate the determination of investors who sink billions of dollars into the technology and infrastructure needed to make harder-to-use materials usable.

These claims of necessity contain a certain degree of truth, but a greater mistruth. The basic truth starts with the fact that fossil fuels permeate nearly every aspect of global capitalism and have a central function powering the relentless pursuit of growth and profits. Thus, the race to expand the tar sands and other forms of extreme fossil energy is indeed necessary to perpetuate the current order of things and, at least in the near-term, the success in this has been reflected in the diminished talk of peak oil. (Here, along with the tar sands, the explosive rise of fracking for oil and gas is especially notable). Of course, extreme energy projects can mean great earnings for financiers from Wall Street to Bay Street, and energy corporations from Calgary to Texas to Europe – though we must be clear that these industries also relate to jobs for ordinary people in countless ways, from the tar sands themselves to automobile assembly lines to a food system that runs on oil. However, the greater mistruth in the claim of necessity for the tar sands lies in the assumption that a growth-dependent, fossil fuel-addicted economic system can and must continue. The reality is that this course is far from inevitable, and that it guarantees disastrous outcomes.

The Line in the Tar Sands: The Growing Resistance

The stakes are rising as the tar sands industry pushes ever harder to expand production, pipelines, and export markets. Fortunately, a growing push-back is mounting against the mighty nexus of corporate and political power on a multitude of fronts. This opposition is grounded in the struggles of Indigenous communities in the Athabasca River Basin, and along existing and planned pipeline corridors. Here, residents have borne the brunt of the ecological devastation and adverse health impacts as their sovereignty has been undermined by both governments and corporations. Indigenous resistance has taken many forms, with community-based efforts to protect their land, water, and autonomy providing the foundation for broader initiatives like the Unist’ot’en Camp,[10] the Yinka Dene Alliance, Moccasins on the Ground gatherings, the Healing Walk, and the Idle No More movement.[11]

As proposals for new and extended pipelines have radiated outwards across the continent, opposition to the tar sands industry has also grown among various non-Indigenous communities and organizations. Movement strategists have often seen pipelines as a strategic vulnerability for the tar sands industry – for two major reasons. First, as suggested earlier, the industry is extremely fearful of how bottlenecks can constrain expansion, and hence both increased pipeline capacity and access to a wider set of refineries are deemed to be essential to continuing growth and investments. At present, much of the tar sands processing capacity is concentrated in the U.S. Midwest, and a glut in bitumen in the region has contributed to falling prices.[12] Tapping into further refinery capacity would increase profits, by avoiding such regional gluts, and by sparing the industry from the costs of building new upgrading facilities in northern Alberta, where these are particularly expensive due to the limits of existing infrastructure in this region. While such bottlenecks remain in place, campaigns against new and expanded pipelines have been able to slow investment in the industry, as investors have become wary of delays with additional pipelines (though it seems that some unfortunately are opting to invest in U.S. shale oil instead.) Rail shipments are growing, but these are more expensive, and cannot substitute for pipelines in terms of the scale of the expansion sought by investors.[13]

The second reason that pipelines are such a strategic vulnerability for the industry is that they provoke resistance by projecting serious eco-health risks onto ever more regions. These threats have been put on stark display in a number of recent spills, including those in the Kalamazoo River in 2010, and in Mayflower, Arkansas, in 2013. The risks of toxic pollution on land and in water bodies have repeatedly served to galvanize frontline mobilizations against pipelines and refineries, and these have grown into a major part of the struggles against the tar sands.

The most well-known pipeline battle has surrounded the Keystone XL proposal, but many other confrontations – ranging from direct actions to court cases – have been intensifying across the U.S. and Canada, as are discussed in several of our chapters. For instance, the Northern Gateway proposal has been met with mounting resistance for the hazards it would pose on land and with soaring tanker traffic moving in coastal waters and around the Haida Gwaii islands. In Ontario and Québec, there have been a range of mobilizations in different communities to oppose the reversal of the flow of the Enbridge Line 9 pipeline, which could enable the company to ship bitumen through southern Ontario and Montreal to the Atlantic coast. Opposition has arisen in response to Enbridge’s Flanagan South Pipeline plan that would flow from the Chicago area to the Gulf Coast. After environmental organizations were unsuccessful in filing an injunction against the project, other strategies have been explored by the Great Plains Tar Sands Resistance network, among others in the region. Anishinaabe communities in Minnesota have staged protests against the Alberta Clipper pipeline that already runs across their land (stretching from Alberta to Superior, Wisconsin) and Enbridge’s plans to dramatically increase the volume of bitumen being pumped through it. In addition, frontline opposition has emerged in response to megaload shipments through the U.S. Northwest, and to stop new tar sands mining in Utah.[14]

Frontline mobilizations from the Athabasca River Basin to sites for existing and proposed pipeline corridors and tar sands refining can be viewed as an extension of decades of environmental justice campaigning in North America, which emerged out of the disproportionate siting of polluting industries, dumps, and resource extraction among poor and often racially marginalized groups.[15] And just as many environmental justice campaigns have become better connected over time, building solidarity based on shared forms of oppression and aspirations, so too are the struggles of frontline communities becoming more entwined.

“The unifying element in these global and local struggles – the proverbial line in the tar sands – is a refusal to accept the legitimacy of the industry and a demand that the bitumen be left in the ground. ”

As the network of resistance has grown, it has increasingly intersected with the efforts of environmental activists and organizations fighting for action on climate change, who recognize how pivotal the tar sands are to any hope of preventing disastrous levels of warming. The unifying element in these global and local struggles – the proverbial line in the tar sands – is a refusal to accept the legitimacy of the industry and a demand that the bitumen be left in the ground.[16]

But beneath this broad goal, there are a diversity of targets and a multiplicity of tactics. The primary targets are, of course, the energy corporations at the helm of the tar sands industry, the Mordor landscape they are creating, and the infrastructure projects they are planning. Secondary targets include things like: government review processes, which promise at least a modicum of public participation; pension funds and financial institutions like the Royal Bank of Canada, which have a crucial role in capitalizing extraction, transport, and refining operations; and campaigns to affect fuel policies in the European Union, which might have forbidden tar sands imports.

Many activists and

organizations have converged in mass demonstrations, such as the rally

to stop Keystone XL in the United States. Indigenous communities and

environmental organizations have presented critical evidence and

arguments to the public hearings and environmental impact assessments

surrounding pipeline and shipment plans, or campaigners have presented

rearguard legal challenges. In Alberta, the tar sands industry is facing

legal challenges from the Beaver Lake Cree, the Athabasca Chipewyan

First Nation, and the Fort McKay First Nation. Land defence struggles

and direct action have ranged from attempts to physically disrupt

production, to establishing blockades and encampments on key sites, to

spectacular banner drops in the tar sands and on Canadian Parliament

buildings. Public education has taken a range of forms, such as speaking

tours and the creation of a range of Internet resources.

The

struggles against the tar sands industry are also intertwined with an

even wider set of movements that are striving toward urgent social,

political, and economic change, as they work to build hopeful

transitions away from a ruinous addiction to fossil fuels and the

pursuit of endless growth. The corporate behemoths driving the tar sands

are implicated in myriad injustices around the world, and they – along

with their political minions – are among the most powerful forces in the

world forestalling such transitions. Challenging these forces also

entails a vast range of efforts to organize our societies more

democratically, equitably, and sustainably, from our food systems to the

design of our cities to the way we heat and power our homes.

It is

hard to assess the degree to which different efforts and even victories

in the short term might ultimately contribute to the big, long-term

objective of keeping the bitumen in the ground. But at the very least,

the resistance has already succeeded in making it clear that the

continuation of the tar sands industry and other extreme energy projects

are far from inevitable, as more and more people come to understand

that these can and must be stopped.

•

Adapted from A Line in the Tar Sands: Struggles for Environmental Justice, edited by Toban Black, Stephen D’Arcy, Tony Weis, and Joshua Kahn Russell (Between the Lines, 2014). A Line in the Tar Sands is a collection of writings from 38 contributors. The collection includes activist, academic, and journalistic perspectives on indigenous, environmentalist, and social justice struggles.

Back to Stephen D’Arcy, Tony Weis & Toban Black’s Author Page | Back to Joshua Kahn’s Author Page