By Kelly Jennings

Strange Horizons

August 16th, 2010

In the interests of self-disclosure, I suppose I should admit that I have been mad for the fiction of Eleanor Arnason since I first came across it back in the nineties. What I found in that first story, “Knapsack Poems,” and in all the rest of her work, which I rapidly sought out, is that quality which first drew me to science fiction, and that which continues to draws me back to science fiction above all other forms of literature: the ability to imagine the world in some other way.

This is not to say that all science fiction does not do this to some extent. Obviously even the most reactionary story is a re-imagining. However, all too often, especially over the past decade, science fiction, particularly American science fiction, has re-imagined a future that tries to draw us toward some unlikely vision of an idealized past. (See John Barnes’s Directive 51 for a recent example in which the goal of the World-Wide Terrorists was to “return” the world to a faux-1950s small-town/suburban paradise). Eleanor Arnason, as she explains in her Wiscon 2004 Guest of Honor speech—revised and reprinted in Mammoths of the Great Plains—hates “the great lie formulated by Margaret Thatcher . . . [t]here is no alternative” (p. 100), and travels further.

Too often we are assured that we have no alternatives. Democracy is the worst form of government except for all the other forms. Capitalism is an unequal distribution of wealth, while communism is an equal distribution of poverty. The way it was in my dad’s house in the suburbs is the way it ought to be forever. Much of contemporary science fiction, far from interrogating these assumptions, endorses them.

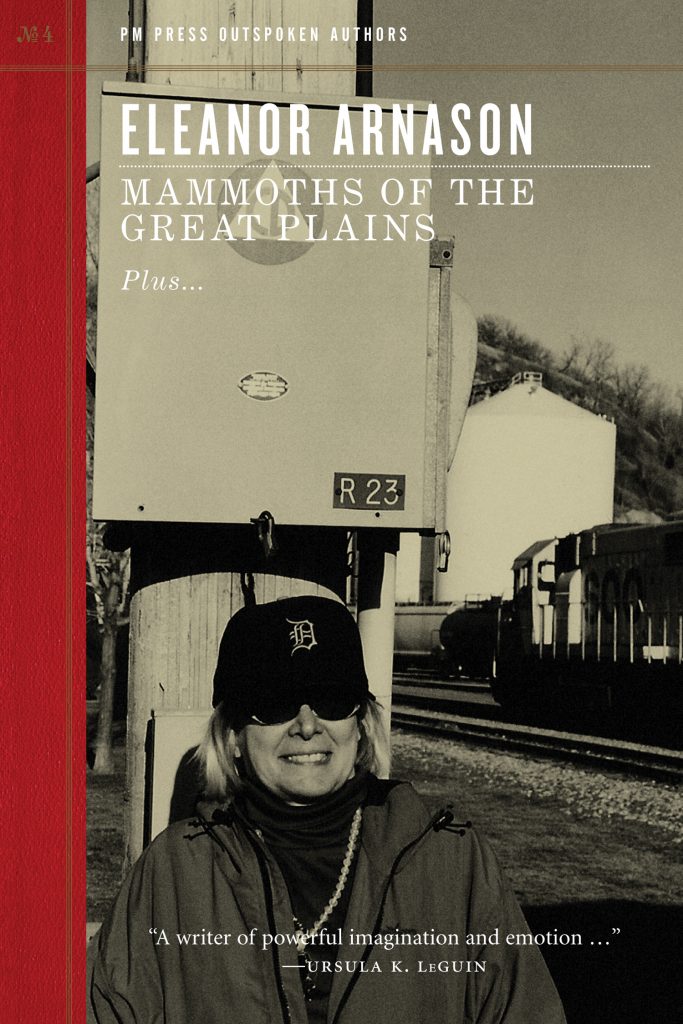

Arnason gives us other ground to walk on. Her book, Mammoths of the Great Plains, a slender volume from the PM Press Outspoken Authors series, is an example of this. Outspoken Authors, launched in 2009, is a series of small, elegant books, all containing a mix of fiction, commentary, and interviews; as is usual with PM Press, the emphasis is political. Arnason’s volume contains the titular short story, her revised Guest of Honor speech from Wiscon, mentioned above, “Writing Science Fiction During World War Three,” and a fascinating interview. The short story may seem at first glance only a well-constructed but standard alternative history, a tale of an America where the mammoths did not die out, unless it is read against the backdrop of contemporary science fiction, and specifically against the backdrop of last year’s wide-ranging debate about race and representation in the science fiction world, or RaceFail, as it came to be known. (Let me add that I don’t know that Arnason means her story to be read this way. I only know I can’t help reading it this way.) In the annals of RaceFail, Patricia Wrede’s The Thirteenth Child (2009) was momentarily famous. Wrede, wanting to write about magic, mammoths, and big cozy pioneer families, decided to write an alternative history in which Native Americans never crossed the land bridge to settle the Americas. If, she apparently reasoned, Native Americans never existed, mammoths and other megafauna might survive.

“Mammoths of The Great Plains” is about a Lakota scientist, Rosa Red Mammoth/ Stevens, who, after she earns her DVM, planning to specialize in large-animal care, is instructed via a dream-visions by a white mammoth that she should, instead, specialize in the study of mammoths; it is also the story of her daughter, Liza Ivanoff, a biologist, likewise visited by dream-mammoths. Together they find a way to save the last of the mammoth herds—these herds, like the great bison herds in our history, and like the Lakota themselves, are being slaughtered as European culture advances. One reason I cannot help reading this story, which is full of small, delightful details, as a reply to Wrede’s The Thirteenth Child, is this passage, early on (the story is being told by Liza to her own granddaughter):

There are white scientists who say Indians killed the Ice-age megafauna . . . Grandmother didn’t believe this. “If we were so good at killing, why did so many large animals survive? Moose, musk oxen, elk, caribou, bison, mountain lions, five kinds of bear. The turkey, for heaven’s sake! They’re big; they can’t really fly; and though I love them, no one who has seen a turkey try to go through a barbed wire fence can claim they are especially adaptable . . . . Are we to believe that our ancestors preferred eating horse and camel to eating bison? Hardly likely!”

Most likely, the animals that died out were killed by changes in the climate, my grandmother said. Everything got drier and hotter after the Glaciers retreated. The mammoth steppe was replaced by short grass prairie. (pp. 15-16)

The passage does go on to make it clear to discerning readers that on their own, mammoths too would not have survived (as they actually did not) in this changed climate; but Arnason is writing a fantasy; and in this history, by magic, and the help of the Lakota, the mammoth make it through right up until the Europeans arrive.

There are other details as well that argue for this story to be read as a gentle reply to Wrede’s book—Rosa crosses the land bridge at one point; all the main characters are Native American; the kind of magic being used is Lakota magic; and the frame story.

It is this frame story which keeps “The Mammoths of the Great Plains” from being too optimistic. Although Liza, the grandmother telling the story to Emma, her part-Lakota/part African granddaughter, does manage, with the help of her Prairie Lake relatives, to save the mammoths, the Alternative America of this alternative history is in dire straits; and it is not due to the invasion of Native Americans over the land bridge or their wasteful hunting habits. This passage is from early in the story.

More white people came up the Missouri—scientists, explorers, hunters, English noblemen, Russian princes. They all shot mammoths, or so it seemed to our ancestors, who watched with horror. We tried to warn the Europeans, but they didn’t listen. Maybe they didn’t care. At some point, we realized they had an idea of the way our country ought to be: full of white farmers on farms like the ones on Europe, even though our land is nothing like the land in England and France. The mammoths would be gone and the bison and us. (p. 22)

Passages like this one, and those in the accompanying interview and Wiscon speech, make it clear that Arnason is not a naively optimistic writer. Though her writing has an optimistic flavor, in the background she is always careful to draw the ruined landscape, the doom that waits if we do not find that path.

Which brings us to Tomb of the Fathers, published by Aqueduct Press. Lydia Duluth, the point of view character in this novel, is a continuing character for Arnason; further, this type of story, a collection of varied characters on a journey through a landscape alien to most of them, is one she has told before, most successfully in Woman of the Iron People (1991). But despite some similarities between these two narratives (Lydia/Lixia for our POV characters; also, the human male in the mix, Olaf, is much like Derek from WoIP, as Bin, the Atch, is similar to Voice of the Waterfall from WoIP), Tomb of the Fathers is fresh enough and, more importantly, Arnason’s writing and her ideas strong enough, to carry the novel.

Part of this has to do with Arnason’s dry humor, which continually catches the reader by surprise. One example, a small one: as we pull away from the space station on which our travelers have met, we pan back for a look at it, and it is not a great wheel, or a spinning torus, or any other standard shape. Rather, it looks “like a large, elaborately folded, white linen napkin, the kind of thing one expected to find in a fancy restaurant . . . All stargate stations looked like folded napkins. No human knew why” (p. 15).

Mainly, though, the strength of the work lies in Arnason’s ability to take us new places. Though this might have been a simple adventure story, as “The Mammoths of the Great Plain” might have been a simple alternative history tale, Arnason, as always, goes further.

Each of her characters, for example, is a complex creation, from Lydia, a former revolutionary who now scouts locations for the Stellar Harvest movie company, to Geena, a genetically-engineered woman created by a mad scientist as a tool for that scientist’s own purposes—who is now engaged in the struggle to define her own existence. Indeed, I hesitated to call Tomb of the Fathers an adventure novel, since adventure novels are, usually, populated by heroes, and as Arnason makes clear, none of her characters see themselves as heroes; nor, as the text suggests, is ‘hero’ a particularly desirable role. Better to be a member of a community, someone who thinks carefully, gathers knowledge, chooses well (though the narrative frequently reminds us that knowing the right choice is not always possible), and takes care of others, so long as it is possible to do that.

Enough self-pity, [Lydia] told herself finally. Think of the positive aspects of the situation. A dozen years without the Stellar Harvest accounting department. Her equipment was close to indestructible and would easily store twelve years worth of data. She would record their struggle to survive, maybe even make a work of art. With Olaf here, her sex life needn’t end. There was Geena as well. The AIs, while not available as sexual partners, were wonderful protection. (p. 101)

Further, like “Mammoths of the Great Plain,” Tomb of the Fathers has a ruined landscape lurking in its background: this planet Lydia and the rest have been stranded on, the original home planet of the Atch, has suffered a catastrophic social war some generations previously, which led to all their males dying off, while the females survived via parthenogenesis. How this can happen has to do with the way the Atch reproduce. It’s interesting and convincing, as Arnason’s alien species always are, and it means that local surviving Atch are clones of their parents, absent minor mutations. However, two problems exist with this reproductive strategy. First, given that most mutations are not beneficial, the quality of local Atch is slowly degrading. Second, among the Atch, the father is the nurturing, and lactating, parent. Though the survivors have found ways to feed and raise their young, they have done so at the price of destroying their civilization. Other, similar destructions lurk throughout the book.

Finally, most adventure stories have a goal, a quest. The end of the story is the end of the quest. The knight slays the dragon, the war is won, the slaves are freed. Here, Arnason, through her characters, acknowledges the bitter truth:

Lydia kept weeping. Why? . . . [It] wasn’t for herself she mourned, or not only for herself. It was for all the intelligent beings caught in the cycle of violence, riding the great wheel that led nowhere, certainly not to Dharma, nor to revolution and a new society. (p. 125)

There is a reason Arnason shows us these broken worlds, where space stations look like napkins, and monuments are raised to scissors and yams, and where regular people, tour guides, smiths, scouts for movie companies, are coping as best they can. It’s true, as her AI character admits, that it is hard to know what to do at a given moment; but (a corollary Arnason does not state, though her characters all demonstrate it, as does her fiction) that moment is where we live, and the only place we can act. Speaking of the banditry and slaughter he has seen among the Atch on his fallen planet, Bin says, “This is how one lives when there is no proper nurture, no reasonable hope, and no real belief in the possibility of a better life” (135). Too often, lately, science fiction writers have been telling us all we can reasonably hope for is a rebuilt past. Here in these books, as in all her fiction, Eleanor Arnason offers dreams of better ways.

Kelly Jennings teaches writing and English in Northwest Arkansas. She is an assistant editor at Crossed Genres.