By Randal Doane

Louder Than War

December 16th, 2014

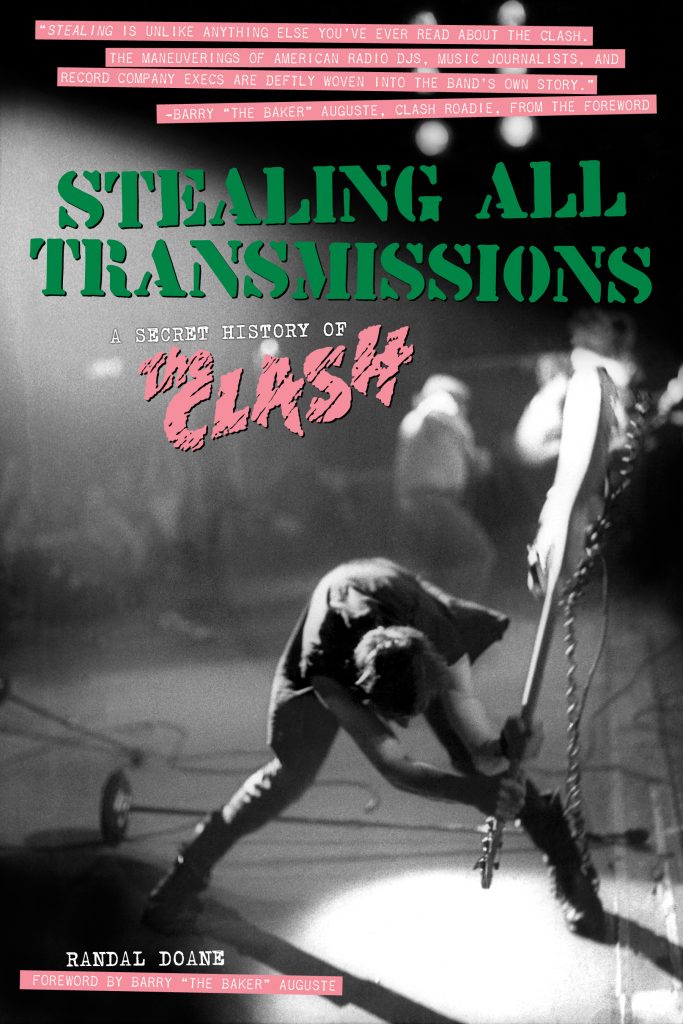

To celebrate the 35th anniversary of The Clash’s London Calling (December 1979, UK; January 1980, US) we present the following excerpts from Stealing All Transmissions: A Secret History of The Clash (2014, PM Press) by Randal Doane, which includes a song-by-song interpretation of the album Rolling Stone dubbed “the best of the 80s”.

Randal’s book was reviewed on Louder Than War by legendary Clash roadie The Baker. You can read his thoughts here and should you wish to buy a copy, as a Xmas present for a loved one, say, go to PM Press’s website. ~

The Clash’s London Calling: “…antidote to Me Generation selfishness and self-defeatism.”

Dan Beck, US product manager at Epic Records, recounted how Kosmo Vinyl fought tooth-and-nail with tongue-in-cheek on behalf of The Clash. “When we came up with the phrase, ‘The Only Band That Matters,’ [Rhodes and Vinyl] literally came in the office and protested it,” Beck told me. “‘That’s horrible!’ they’d say, and they’d be bursting with laughter.” Their laughter arose from the gap between the fantasy of the authenticity police and the aims of The Clash, which Strummer articulated prior to their first passage across the Atlantic: “We’ve got loads of contradictions for you … we’re trying to do something new; we’re trying to be the greatest group in the world, and that also means the biggest. At the same time, we’re trying to be radical — I mean, we never want to be really respectable — and maybe the two can’t coexist, but we’ll try.”

In the ensuing years, the staff at Epic came to understand and respect The Clash’s reflexive engagement with these contradictions. As radio expanded its sonic palette, and The Clash continued to shift musical directions, the moment ripened for airwave domination. After the release of London Calling, McCarrell told Vinyl, “Look, if we do this right, we can sell millions of records here. Are you guys okay with that?” Vinyl smiled and replied, “Yes. Yes we are.”

London Calling was released in the UK in December 1979, and in the United States the following month. If Give ‘Em Enough Rope was, as Creem’s Dave DiMartino surmised, “the carefully measured, laboriously drawn-out Pearlman affair,” London Calling represented a burst of freedom from their estrangement. For the March issue of Trouser Press, Chris Salewicz penned an affirmative profile of more than three thousand words, hoping plainly that London Calling would become “the definitive ’70s rock ’n’ roll record, an ironic antidote to Me Generation selfishness and self-defeatism.” Between the bookends of the anthemic titular single, and the pop-radio-friendly “Train in Vain,” the Village Voice’s John Piccarella savored The Clash’s facility with the three “r’s”: rockabilly, rhythm and blues, and reggae, especially. Four months after the U.S. release of London Calling, Rolling Stone obliged once again. In a lengthy review essay for the April 3 issue, Tom Carson described the album as “spacious and extravagant,” relished the historical grandeur of “Spanish Bombs,” and celebrated the stubborn spirit rising in the coda of “Death or Glory.” For the Soho Weekly, Bangs offered tempered enthusiasm, professing that he missed “the edge, the snarl, the unremitting tension” of earlier LPs. Still, Bangs reckoned, “There’s an ease and a rightness about them that’s as gratifying as the Stones of Beggars Banquet, and probably a good deal more straight-on.”

All four sides of Calling resonate with ease and rightness. It’s gritty where it should be, and gorgeous everywhere else. It’s a reckoning with the world of rock ’n’ roll, a negation of the narrow codes of punk, and a tribute to what The Clash achieved in Vanilla Studios, with the help of The Baker and Johnny Green, Gallagher and the horn players — and, for a little while, minimal interference from anyone else. Jones bore responsibility for sequencing the album and did a brilliant job. If the antics of “rock’n’roll Mick” would grow tiresome, even loathsome, in the next few years, his understanding of how to sequence an album reflected his diligent study of exemplary rock LPs. He also understood the pop aesthetic of the fade-out at the cadence, which he and Price employed on thirteen of the nineteen tracks on London Calling.

In the paragraphs that follow, I imagine London Calling as a cinematic montage, and The Clash as a single, peripatetic protagonist, wandering the avenues and alleys of London and New York, picking up stories and sounds in al fresco cafes, in movies in Times Square, and behind barricades in Brixton. My aim here is not to claim London Calling as a concept album, but to take stock of the aesthetic impact of the rarest of things: a triumphant double album.

Side One

Side one commences, of course, with the opening bars of “London Calling,” which are straight-on indeed. Our protagonist stands by the river, wondering aloud, plaintively, about the fate of this great city — of all cities everywhere — should nuclear errors persist. The anthem commences with Strummer’s downstrokes and, for the moment, Headon’s kit remains deep in the mix. Simonon joins in with the haunting bass refrain, and now Headon’s drums charge to the foreground, marching the band to the opening verse. The amber waves of grain are desiccated, and meltdown awaits. The upshot? There’s no more Beatlemania in the form of The Jam — cheer up kids! Strummer sustains a hot vocal urgency from beginning to end, while the warm vocals of Jones and Simonon offer a reassuring sense of calm — a contrast reprised to great effect for the next hour. At the coda, the ease of the fade-out is betrayed by the warning transmission of Morse code, tapped out by Jones on his guitar, over Strummer’s receding confession.

Around the corner, our protagonist encounters a lovers’ quarrel. The woman sits behind the wheel of a shiny, well-chromed gas guzzler, and her ex-lover is awe-struck. But is it the presence of the Cadillac, or the loss of his woman, that he finds most vexing? Here The Clash break the rules once again, and include on track two their homage to Vince Taylor, a late-1950s rock ’n’ roller, and the subject of the imaginative bio-LP Ziggy Stardust. (After 1965, covers rarely appeared earlier than track four on canonical LPs.)

Side one closes with tales of temptation and addiction. The Baker’s glorious whistling opens “Jimmy Jazz,” and introduces the thick arm of the law to the narrative. The action begins at the outdoor seating of a café, and the police approach the owner, who turns coy trickster, within earshot of our protagonist. “Jimmy? Here? He was, but not now.” Strummer’s slurred lyrics, over musical accompaniment with R&B horns and a relaxed reggae tempo, provides a hint for American listeners, who may have relied upon monikers other than “jazz” for marijuana. “Jazz’s” moderate rhythmic complexity serves as a nice bridge to the uptempo desperation of “Hateful,” in which our protagonist wanders into Brighton’s Powis Square, and turns a keen eye on a junkie he once knew, now bereft of mates and his memory. The following morning, on London’s East End, he raises the prospects of lager as the breakfast of champions and, if there’s no work to be had on Maggie Thatcher’s Farm, the rude boys are, set to rights, doomed to fail. In its vinyl form, it’s a triumphant end to side one, with Jones and Strummer barging in on one another mid-stanza, in chorus and verse — a feature well-reprised on a handful of songs that remain, and on “Spanish Bombs” in particular.

Side Two

On side two, our protagonist finds himself in midtown Manhattan, and stops for coffee to catch up on his reading. He tarries in a bilingual daydream about anarchists’ fantasies in “Spanish Bombs.” Upon leaving the cafe, he crosses 42nd Street and spies pimps and hustlers working the beat beneath the Mayfair marquee, where the films of Montgomery Clift, the drinking-and-driving anti-hero of “The Right Profile,” once played. Our protagonist hits the shops on Broadway, but neither discotheque albums nor alcohol provides little more than fleeting satisfaction (“Lost in the Supermarket”). Back in Brixton, he encounters a band of young men who solicit his counsel. “Don’t believe!,” he shouts. “Refuse the clampdown! They’re not after your money. They’ll take much more than that!” He moves along, chin low against the wind, and notices the fraying hem in his navy pants, and the scuff atop his chestnut boots. That night, somebody’s been murdered, and now it’s rebels galore, awash in firearms, dreaming of death and glory, with fingers on the triggers of the “Guns of Brixton.”

Side Three

For side three, in Greenwich Village, our protagonist decides he needs a larger audience, and takes to a ramshackle stage at Washington Square Park. To bolster his faith in nearly clean living, he offers a rousing cover of Clive Alphonso’s “Wrong ’Em Boyo.” On vinyl, Jones and Simonon offer backing vocals at seemingly random intervals, and evoke — in its absence — the repressive order of the Rope sessions. The joy and ease of the vocal accents, along with the riff-heavy refrain of the horn section, confirms their facility with the musical codes of reggae. The urgency becomes palpable, and the stage becomes a soap box. In the rousing “Death or Glory,” the options appear to our aging protagonist as neither palatable nor possible, and our hero extends compassion to the tattooed-knuckled punk trying to get his baffled kids to understand . . . what exactly? He wishes he knew.

In “Koka Kola,” our protagonist returns to the street, checking out the billboards along Madison Avenue, wondering about the world of the ad man, and whether it’s life or death that goes better with coke. In the grooves, Headon keeps a resolute tempo, Simonon turns in some lovely bass figures, and the whole thing speeds by in under two minutes. Around the inarticulate message of “Lover’s Rock,” our protagonist returns to the Odeon in Times Square for a double feature of The Cincinnati Kid, an uber-cool card sharp played by Steve McQueen (“The Card Cheat”), and The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, starring Rita-Hayworth-favorite Glenn Ford (“Four Horsemen”).

As the credits roll, he leaves inspired, cocky even, and returns to Washington Square Park. Back on the bandstand, he affirms his tenacity with the hard-charging “I’m Not Down,” and wraps things up with the more conciliatory “Revolution Rock.” His between-verse patter indicates his need to keep his sights modest, to take any gig he can get, and to play in whatever musical style the host demands. And that is nearly how the montage concludes — from nuclear meltdown to the exigencies of the market, from the band’s last gesture as a punk rock group, to their steady hands as reggae stylists, and the territory covered over the first eighteen tracks is vast and deep, black and white, and open to possibility. Our protagonist knows, though, for a kid raised in Wilmcote House, there are few options more alluring than singing for a rock’n’roll band. So he packs up his guitar, heads north on 5th Avenue, veers left onto Broadway, through Times Square, and into the Brill Building, with a one-song tape in hand, praying his efforts won’t end in vain. ~

This article first appeared on Randal Doane’s blog. You can purchase Stealing All Transmissions: A Secret History of The Clash here.

Randal Doane works at Oberlin College. He dispatches on punk and rock ‘n’ roll as @stealingclash on Twitter and at stealingalltransmissions.wordpress.com. His Louder Than War author’s archive is here.

– See more at:

http://louderthanwar.com/the-clashs-london-calling-reaches-its-thirty-fifth-birthday-randal-doane-writes-with-selections-from-stealing-all-transmissions-a-secret-history-of-the-clash/#sthash.wV0WLccb.dpufhttp://louderthanwar.com/the-clashs-london-calling-reaches-its-thirty-fifth-birthday-randal-doane-writes-with-selections-from-stealing-all-transmissions-a-secret-history-of-the-clash/

To

celebrate the 35th anniversary of The Clash’s London Calling (December

1979, UK; January 1980, US) we present the following excerpts from Stealing All Transmissions: A Secret History of The Clash

(2014, PM Press) by Randal Doane, which includes a song-by-song

interpretation of the album Rolling Stone dubbed “the best of the 80s”.

Randal’s book was reviewed on Louder Than War by legendary Clash roadie The Baker. You can read his thoughts here and should you wish to buy a copy, as a Xmas present for a loved one, say, go to PM Press’s website.

The Clash’s London Calling: “…antidote to Me Generation selfishness and self-defeatism.”

Dan Beck, US product manager at Epic Records, recounted how Kosmo Vinyl fought tooth-and-nail with tongue-in-cheek on behalf of The Clash. “When we came up with the phrase, ‘The Only Band That Matters,’ [Rhodes and Vinyl] literally came in the office and protested it,” Beck told me. “‘That’s horrible!’ they’d say, and they’d be bursting with laughter.” Their laughter arose from the gap between the fantasy of the authenticity police and the aims of The Clash, which Strummer articulated prior to their first passage across the Atlantic: “We’ve got loads of contradictions for you … we’re trying to do something new; we’re trying to be the greatest group in the world, and that also means the biggest. At the same time, we’re trying to be radical — I mean, we never want to be really respectable — and maybe the two can’t coexist, but we’ll try.”

In the ensuing years, the staff at Epic came to understand and respect The Clash’s reflexive engagement with these contradictions. As radio expanded its sonic palette, and The Clash continued to shift musical directions, the moment ripened for airwave domination. After the release of London Calling, McCarrell told Vinyl, “Look, if we do this right, we can sell millions of records here. Are you guys okay with that?” Vinyl smiled and replied, “Yes. Yes we are.”

London Calling was released in the UK in December 1979, and in the United States the following month. If Give ‘Em Enough Rope was, as Creem’s Dave DiMartino surmised, “the carefully measured, laboriously drawn-out Pearlman affair,” London Calling represented a burst of freedom from their estrangement. For the March issue of Trouser Press, Chris Salewicz penned an affirmative profile of more than three thousand words, hoping plainly that London Calling would become “the definitive ’70s rock ’n’ roll record, an ironic antidote to Me Generation selfishness and self-defeatism.” Between the bookends of the anthemic titular single, and the pop-radio-friendly “Train in Vain,” the Village Voice’s John Piccarella savored The Clash’s facility with the three “r’s”: rockabilly, rhythm and blues, and reggae, especially. Four months after the U.S. release of London Calling, Rolling Stone obliged once again. In a lengthy review essay for the April 3 issue, Tom Carson described the album as “spacious and extravagant,” relished the historical grandeur of “Spanish Bombs,” and celebrated the stubborn spirit rising in the coda of “Death or Glory.” For the Soho Weekly, Bangs offered tempered enthusiasm, professing that he missed “the edge, the snarl, the unremitting tension” of earlier LPs. Still, Bangs reckoned, “There’s an ease and a rightness about them that’s as gratifying as the Stones of Beggars Banquet, and probably a good deal more straight-on.”

All four sides of Calling resonate with ease and rightness. It’s gritty where it should be, and gorgeous everywhere else. It’s a reckoning with the world of rock ’n’ roll, a negation of the narrow codes of punk, and a tribute to what The Clash achieved in Vanilla Studios, with the help of The Baker and Johnny Green, Gallagher and the horn players — and, for a little while, minimal interference from anyone else. Jones bore responsibility for sequencing the album and did a brilliant job. If the antics of “rock’n’roll Mick” would grow tiresome, even loathsome, in the next few years, his understanding of how to sequence an album reflected his diligent study of exemplary rock LPs. He also understood the pop aesthetic of the fade-out at the cadence, which he and Price employed on thirteen of the nineteen tracks on London Calling.

In the paragraphs that follow, I imagine London Calling as a cinematic montage, and The Clash as a single, peripatetic protagonist, wandering the avenues and alleys of London and New York, picking up stories and sounds in al fresco cafes, in movies in Times Square, and behind barricades in Brixton. My aim here is not to claim London Calling as a concept album, but to take stock of the aesthetic impact of the rarest of things: a triumphant double album.

Side One

Side one commences, of course, with the opening bars of “London Calling,” which are straight-on indeed. Our protagonist stands by the river, wondering aloud, plaintively, about the fate of this great city — of all cities everywhere — should nuclear errors persist. The anthem commences with Strummer’s downstrokes and, for the moment, Headon’s kit remains deep in the mix. Simonon joins in with the haunting bass refrain, and now Headon’s drums charge to the foreground, marching the band to the opening verse. The amber waves of grain are desiccated, and meltdown awaits. The upshot? There’s no more Beatlemania in the form of The Jam — cheer up kids! Strummer sustains a hot vocal urgency from beginning to end, while the warm vocals of Jones and Simonon offer a reassuring sense of calm — a contrast reprised to great effect for the next hour. At the coda, the ease of the fade-out is betrayed by the warning transmission of Morse code, tapped out by Jones on his guitar, over Strummer’s receding confession.

Around the corner, our protagonist encounters a lovers’ quarrel. The woman sits behind the wheel of a shiny, well-chromed gas guzzler, and her ex-lover is awe-struck. But is it the presence of the Cadillac, or the loss of his woman, that he finds most vexing? Here The Clash break the rules once again, and include on track two their homage to Vince Taylor, a late-1950s rock ’n’ roller, and the subject of the imaginative bio-LP Ziggy Stardust. (After 1965, covers rarely appeared earlier than track four on canonical LPs.)

Side one closes with tales of temptation

and addiction. The Baker’s glorious whistling opens “Jimmy Jazz,” and

introduces the thick arm of the law to the narrative. The action begins

at the outdoor seating of a café, and the police approach the owner, who

turns coy trickster, within earshot of our protagonist. “Jimmy? Here?

He was, but not now.” Strummer’s slurred lyrics, over musical

accompaniment with R&B horns and a relaxed reggae tempo, provides a

hint for

American listeners, who may have relied upon monikers other than “jazz” for marijuana.

“Jazz’s”

moderate rhythmic complexity serves as a nice bridge to the uptempo

desperation of “Hateful,” in which our protagonist wanders into

Brighton’s Powis Square, and turns a keen eye on a junkie he once knew,

now bereft of mates and his memory. The following morning, on London’s

East End, he raises the prospects of lager as the breakfast of champions

and, if there’s no work to be had on Maggie Thatcher’s Farm, the rude

boys are, set to rights, doomed to fail. In its vinyl form, it’s a

triumphant end to side one, with Jones and Strummer barging in on one

another mid-stanza, in chorus and verse — a feature well-reprised on a

handful of songs that remain, and on “Spanish Bombs” in particular.

Side Two

On side two, our protagonist finds himself in midtown Manhattan, and stops for coffee to catch up on his reading. He tarries in a bilingual daydream about anarchists’ fantasies in “Spanish Bombs.” Upon leaving the cafe, he crosses 42nd Street and spies pimps and hustlers working the beat beneath the Mayfair marquee, where the films of Montgomery Clift, the drinking-and-driving anti-hero of “The Right Profile,” once played. Our protagonist hits the shops on Broadway, but neither discotheque albums nor alcohol provides little more than fleeting satisfaction (“Lost in the Supermarket”). Back in Brixton, he encounters a band of young men who solicit his counsel. “Don’t believe!,” he shouts. “Refuse the clampdown! They’re not after your money. They’ll take much more than that!” He moves along, chin low against the wind, and notices the fraying hem in his navy pants, and the scuff atop his chestnut boots. That night, somebody’s been murdered, and now it’s rebels galore, awash in firearms, dreaming of death and glory, with fingers on the triggers of the “Guns of Brixton.”

Side Three

For side three, in Greenwich Village, our protagonist decides he needs a larger audience, and takes to a ramshackle stage at Washington Square Park. To bolster his faith in nearly clean living, he offers a rousing cover of Clive Alphonso’s “Wrong ’Em Boyo.” On vinyl, Jones and Simonon offer backing vocals at seemingly random intervals, and evoke — in its absence — the repressive order of the Rope sessions. The joy and ease of the vocal accents, along with the riff-heavy refrain of the horn section, confirms their facility with the musical codes of reggae. The urgency becomes palpable, and the stage becomes a soap box. In the rousing “Death or Glory,” the options appear to our aging protagonist as neither palatable nor possible, and our hero extends compassion to the tattooed-knuckled punk trying to get his baffled kids to understand . . . what exactly? He wishes he knew.

In “Koka Kola,” our protagonist returns to the street, checking out the billboards along Madison Avenue, wondering about the world of the ad man, and whether it’s life or death that goes better with coke. In the grooves, Headon keeps a resolute tempo, Simonon turns in some lovely bass figures, and the whole thing speeds by in under two minutes. Around the inarticulate message of “Lover’s Rock,” our protagonist returns to the Odeon in Times Square for a double feature of The Cincinnati Kid, an uber-cool card sharp played by Steve McQueen (“The Card Cheat”), and The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, starring Rita-Hayworth-favorite Glenn Ford (“Four Horsemen”).

As the credits roll, he leaves inspired, cocky even, and returns to Washington Square Park. Back on the bandstand, he affirms his tenacity with the hard-charging “I’m Not Down,” and wraps things up with the more conciliatory “Revolution Rock.” His between-verse patter indicates his need to keep his sights modest, to take any gig he can get, and to play in whatever musical style the host demands. And that is nearly how the montage concludes — from nuclear meltdown to the exigencies of the market, from the band’s last gesture as a punk rock group, to their steady hands as reggae stylists, and the territory covered over the first eighteen tracks is vast and deep, black and white, and open to possibility. Our protagonist knows, though, for a kid raised in Wilmcote House, there are few options more alluring than singing for a rock’n’roll band. So he packs up his guitar, heads north on 5th Avenue, veers left onto Broadway, through Times Square, and into the Brill Building, with a one-song tape in hand, praying his efforts won’t end in vain.

This article first appeared on Randal Doane’s blog.

Randal Doane works at Oberlin College. He dispatches on punk and rock ‘n’ roll as @stealingclash on Twitter and at stealingalltransmissions.wordpress.com. His Louder Than War author’s archive is here.