by Matthew Duersten

LA Magazine

December 16, 2014

2014 was the year of big music books: splashy, spendy doorstops on the likes of Lenny Kravitz, The Rolling Stones (13 lbs., $150), Jimmy Page, Marianne Faithfull, Leonard Cohen, and Blue Note Records. (Even experimental crank John Cage was the subject of a lavish book.) There were also handsome, high-profile new bios of Mick Fleetwood, Billy Idol, Billy Joel, Jerry Lee Lewis, Carlos Santana, and even One Direction, not to mention more entries in the endlessly swelling Elvis, Cobain, and Beatles libraries.

But “little” music books have been hanging in by their fingernails. To clarify: “Little” doesn’t just mean physically small (although some of these you could definitely stuff in a stocking) but also overlooked, specific or esoteric topics, or published (or self-published) through a small press—labors of love from (and for) the Little Guy. These “little” offerings still pack a big punch:

FOR THE CONSPIRACY THEORIST

If you saw Room 237, the documentary about the conspiracy theories surrounding Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining, these books might remind you that rock music has its own subtexts. In Season of the Witch: How the Occult Saved Rock and Roll (Tarcher, $27.95), BoingBoing and Believer scribe Peter Berbegal recounts being hooked into sometimes “explicit, sometimes hidden occult language of rock” through the ’70s albums of his older brother, who inscribed a quote from Satanist Aleister Crowley (“Do what thou wilt”) in the vinyl grooves of Led Zeppelin III. Despite covering approximately 2,000 years of human history, the book is a compact 288 pages. Harvard Divinity School grad Bebergal (whose own last name sounds like a conjured demonic force) connects the imagery of the Egyptians, Southern Voodoo, European Christianity, Paganism, and Burning Man with the music and aesthetic visions of bands like Hawkwind, The Rolling Stones, Blue Oyster Cult, Throbbing Gristle, and David Bowie. (Fun fact: Daryl Hall put his ka-ching pop career in jeopardy—as well as his partnership with John Oates—when he recorded Sacred Songs, a solo album based on the writings of Aleister Crowley. No joke, folks.)

The occult also plays a part in Weird Scenes Inside the Canyon: Laurel Canyon, Covert Ops & the Dark Heart of the Hippie Dream (Headpress, $24.95), David McGowan’s whackadoo rendering of L.A.’s countercultural Olympus through the lens of a conspiracy junkie who doesn’t get out much. Should you or should you not buy McGowan’s main thesis—that the hippie enclave just above the Sunset Strip was a toxic labyrinth of underground tunnels, covert military installations, and criminally compromised countercultural icons—part of the fun of this book is McGowan’s autodidact defensiveness (“I have no desire to serve as a publicist for the estates of Jim Morrison, John Phillips, or Frank Zappa…”) and his snarky sense of humor that occasionally veers into bitterness. It’s an entertaining read halfway between William Goldman’s fevered biographical dissections and the jump-cut paranoia of golden-age Oliver Stone.

FOR THE ENTERPRISING PUNK

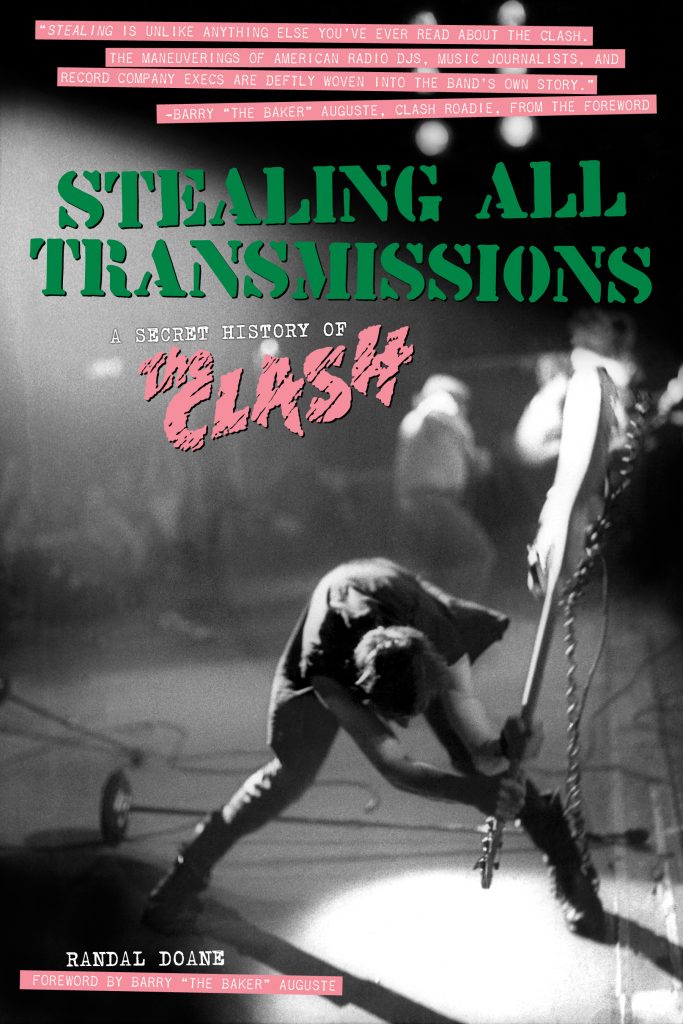

The scrappy, Bay Area-based PM Press might win the “Little Book” award for 2014. Randal Doane’s Stealing All Transmissions: A Secret History of the Clash (PM, $15.95), which began as an article he pitched to The New Yorker, clocks in at around 130 pages, and Alex Ogg’s Dead Kennedys: Fresh Fruit for Rotting Vegetables: The Early Years (PM, $17.95), originally composed as liner notes, is only 200 pages. Both are similar tales of scruffy underdogs attempting to cross the moat of the Big Time Music Industry. Where they diverge is how their subjects went about doing it. Doane’s account burns through a three-year period (’79-’81) when a group of U.S. promoters, retailers, rock writers, fans, and radio DJs endeavored to break The Clash in America. This culminated in the band, who had been suffering from a nasty press backlash in their home country, being signed to CBS and recording their artistic triumph London Calling.

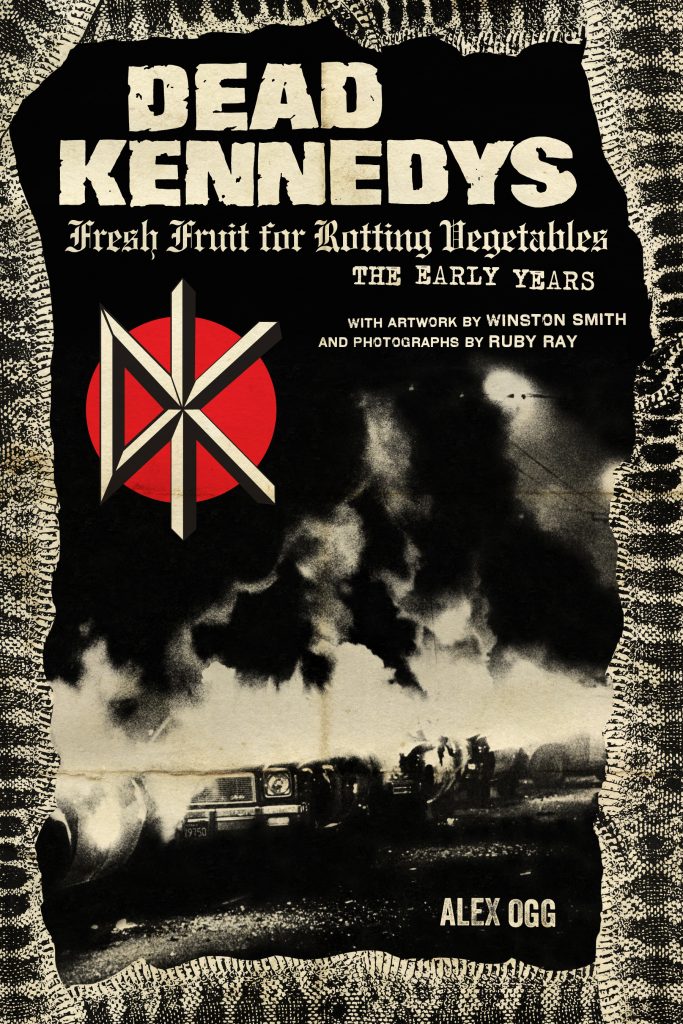

Ogg’s book about the making of the notorious hardcore foursome Dead Kennedys’ first album covers almost the same time period from opposite circumstances. The Dead Kennedys couldn’t get arrested (creatively speaking) in America and turned toward British indie label Cherry Red to release Fresh Fruit for Rotting Vegetables, which, in the author’s words, “outclasses London Calling, or the Sex Pistols’ and the Ramones’ debut albums.” Lead singer and agitator Jello Biafra (né Eric Boucher from Boulder, Colorado) gave punk purist Ian McKaye a Left Coast run for his money, being rabidly anti-corporate—Biafra vociferously opposed the band signing to Polydor Records—and anti-U.S. foreign policy during the earliest days of Reagan’s presidency. There’s even a life-lesson in how the most populist creative visions can end with all the band members suing each other.

FOR THE ARMCHAIR SOCIOLOGIST

Published just three weeks before its subject passed away at the elegant age of 92, Edward Berger’s Softly, With Feeling: Joe Wilder and the Breaking of Barriers in American Music (Temple UP, $35) traces the life of the jazz trumpeter from the summer of 1938, when the 16-year-old played a concert at Philadelphia’s Girard College, through his experiences as a black musician in pre-Civil Rights America. Unable to fulfill his dream of being a classical trumpeter, Wilder took an alternate route through the legendary bands of Dizzy Gillespie, Lionel Hampton, and Jimmie Lunceford. In the 1950s he became the first African American musician to break the color barrier in the Broadway pit orchestras and New York TV-studio bands. Columbia University lecturer Hisham Ali’s skillful narrative in Rebel Music: Race, Empire, and the New Muslim Youth Culture (Pantheon, $16.95) begins at the epicenter of American hip-hop (The South Bronx) then follows its resonating soundwaves all over the globe from Brazil and Antwerp to Algeria and Tunis to Copenhagen, and the young transnational Muslim youth who have been energized (and not, as Aidi emphasizes, “radicalized’) by African-American culture.

FOR THE WONK

These two wide-ranging offerings are as expensive as they are arcane, but they’re perfect for the friend who friend likes curling up in a chair in the corner while the rest of the party plays Cards Against Humanity. David Grubbs’s Records Ruin the Landscape: John Cage, the Sixties, and Sound Recording (Duke UP, $23.95) seems borne from a Ph.D. thesis, but its topic is fascinating: the uneasy history that experimental musicians of the ’60s and ’70s have with the recording process. (Hint: It’s similar to the relationship between a butterfly and a mason jar.)

Portland alt-jazz musician Andrew Durkin’s refreshingly unstodgy Decomposition: A Music Manifesto (Pantheon,

$28.95) begins with a bad joke about Beethoven, illustrating the

author’s purpose “to demythologize music without demeaning it.” U2,

Bandcamp, Yo-Yo Ma, and Lady Gaga (among many others) all figure into

the discussion as examples of what he dubs “the global music ecosystem,”

an “unwieldy network” held together by emphasis on “authorship” (the

notion that music “springs full-blown and ex nihilo from the minds of

isolated individuals”) and “authenticity” (“a singularly true ideal

experience of music that trumps all others”). The misconception of both,

Durkin argues, is what helps transform music from its organic,

unmediated state to a co-opted commodity. Heavy stuff but ideal for

those who can handle it.

Dead Kennedys: Fresh Fruit for Rotting Vegetables, The Early Years:

Stealing All Transmissions: A Secret History of The Clash:

Back to Randal Doane’s Author Page | Back to Alex Ogg’s Author Page | Back to Winston Smith’s Artist Page