by Peter Seyferth

Anarchist Studies 23-2

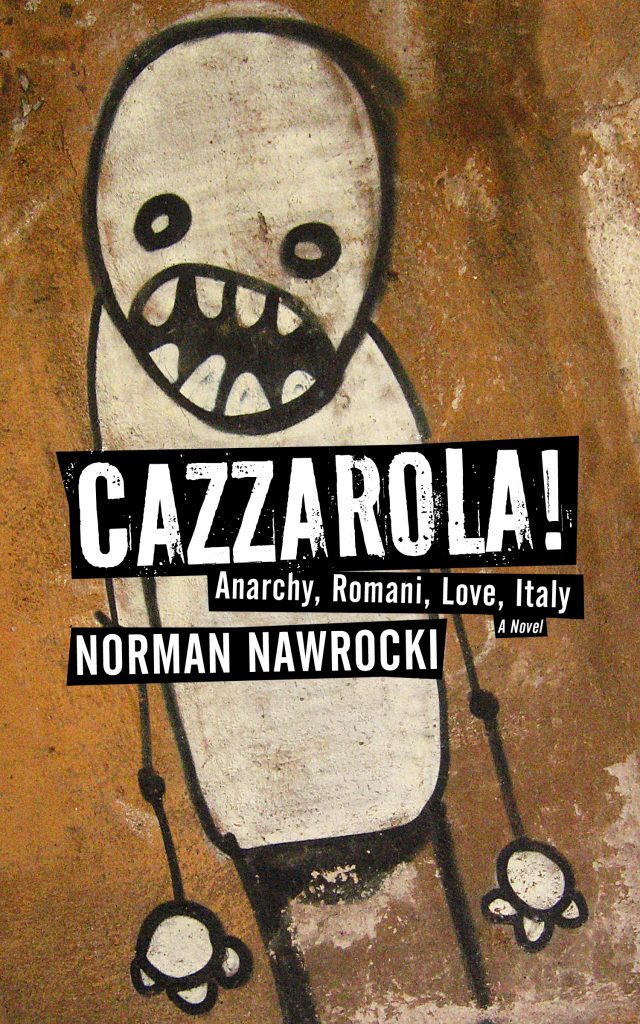

In a time when xenophobia and racism gain weight in European politics and some boneheads ‘rebelliously’ reproduce relationships of hierarchy and oppression by setting fire to refugee camps, a novel like Cazzarola! is very relevant because it brings to life both the history of real rebels (anarchists) and the story of recipients of hate crimes and state crimes (Romani).

Cazzarola! tells the stories of Antonio Discordia, his love, and his family. Antonio is a student, a musician, and an anarchist. He lives his punk rock life- style with beer and activism, like many of us. But then he falls in love with Cinka Dinicu, a beautiful violin player. Cinka is a Romani, and this makes their love very complicated. Romans and Romani do not easily fit, they live in different, almost incompatible worlds. While Antonio is not rich (he has to share a flat), Cinka is bitterly poor. She lives in a slummy camp with naked soil for a floor in the shoddy shed she shares with her whole family. She has to earn a living for all of them by playing her violin in public places, always being on the lookout against dangerous Italians who might attack her. Cinka has not chosen a romantic ‘Gypsy’ lifestyle, she’d rather live in a comfortable home, accepted by her neighbours – but Italy won’t let her. Cazzarola! made me feel the difficult and dangerous situation in which Romani people have to live. Bored youths, agitated neo-fascists, and greedy politi- cians beat them up, torch their homes and shops, tear down their camps, murder them. Cinka is in constant fear. Antonio brings her food and mattresses and job opportunities, and can even give her a day and a night of bliss – but he cannot save her. From his privileged perspective he sees opportunities where Cinka sees dangers. When Cinka gets pregnant, Antonio has no idea of the vengeance this might evoke: Cinka was promised to a Romanian village guy when she was a girl. And when Antonio and his friends increase their anti-fascist and anti-racist actions in an attempt to help the immigrants and the disenfranchised, they may just make things more dangerous …

Activism is the second storyline of the novel. The Discordias are a family of anar- chists. Antonio’s great-grandfather tells the tales of long, hard strikes in the nineteenth century, resistance to Mussolini’s blackshirts and to the Duce himself, autonomous actions in the 1970s, and anti-fascist action in our times – this is the continuing tradi- tion of the struggle for liberation. Nawrocki contrasts this to short descriptions of the way old and new fascists plan and carry out their violent crimes – this is the contin- uing tradition of oppression. In his blurb on Cazzarola!, Davide Turcato compares Nawrocki’s novel to Bertolucci’s movie 1900. That is not far-fetched, although in Cazzarola! the Communist Party is much more clearly exposed as the class traitor it actually was. Sometimes I had the suspicion that Nawrocki wanted to smuggle history lessons into his novel, but then he subverts his teaching with dizzying changes between storylines, and with intense descriptions of colours, temperatures, sounds, and smells. Cazzarola! is not a book from which to learn facts about Italian anarchism or Romani culture (for that, visit the information-rich websites Nawrocki lists in the back of the book). Rather, Cazzarola! touches the heart, shakes it between wrath and sympathy. It depicts Italy as a beautiful and horrible country. It made me wish Italy and the world could be pushed towards more beauty. And it clearly identified xeno- phobia, racism and fascism, along with their accomplices capitalism and state, as the source of ugliness.

Back to Norman Nawrocki’s Author Page