By Andrej Grubacic

ZNet

January 10th, 2009

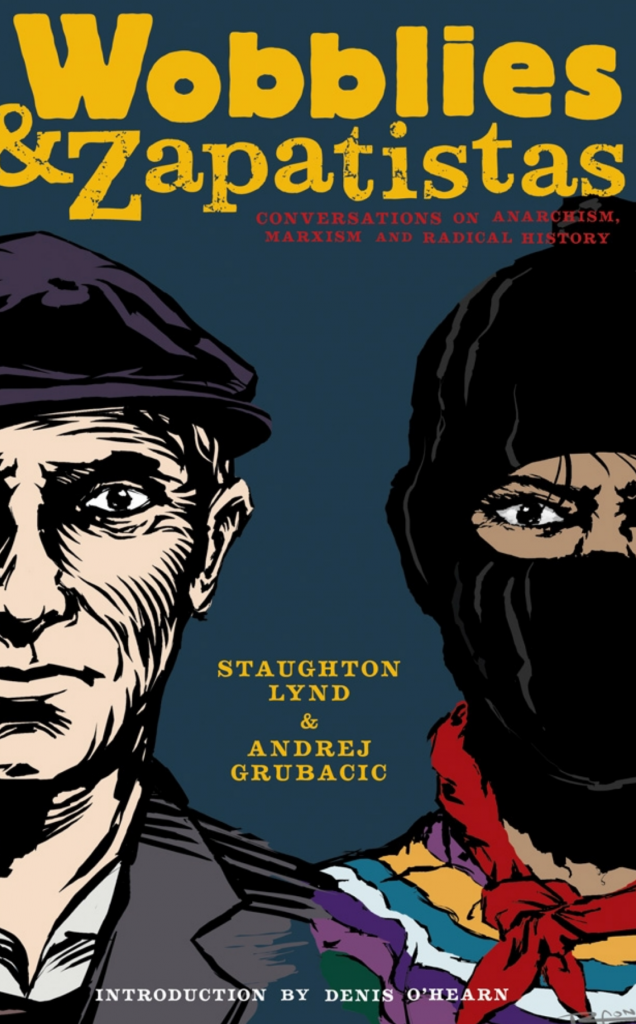

1. Can you tell ZNet, please, what Wobblies and Zapatistas is about? What is it trying to communicate?

Staughton: The book is about the need for Marxists and anarchists to lay down their ideological weapons and create a single Left resistance to what capitalism is doing to the world. The hostility between the two traditions is a little like a feud between extended families handed down from generation to generation: Hatfields and McCoys in American history, or the families of Romeo and Juliet. In reality Marxism and anarchism should be like two hands, the one analyzing the structure of things, the other throwing up unending prefigurative initiatives. Neither tradition has been so successful that it can speak of the other with lofty dismissal or contempt. We need each other.

Andrej: Our way of distancing ourselves from this Shakespearean relationship between anarchism and Marxism is by using the notion of direct action and accompaniment. In so doing we arrive at a “Haymarket synthesis,” recently revived by the Zapatistas, a synthesis that we see emerging over and over again throughout American history. We start with the Haymarket anarchists and the so called “Chicago idea”; we go on to explore histories of such movements as the Industrial Workers of the World, Zapatistas, as well as individuals, such as Simone Weil or Edward Thompson, who sought a fusion between these two traditions. By accompaniment we mean a specific form of mutual aid and praxis where the activist and the oppressed person walk side by side, sharing bread, as the phrase goes, sharing specific knowledge and experience. We speak about a relation between direct action and theory. Both Staughton and myself are very weary of recent fashionable “high theory” that speaks in “multitudes,” and that tends to be, well, incomprehensible; we advocate instead a “low theory,” a theory that arises from practice, as well as what Staughton describes above as a structural analysis of things. We think that the new movement needs to be concerned with strategy and program, that it needs to develop a serious strategy and a serious program, that anarchists need to learn how to swim in the sea of the people, and that we need to do our best to re-create a truly non-sectarian community of struggle that would resemble the experience of mass working class movements such as the one of the Chicago anarchists who “invented a peculiar brand of socialism” of the sort that we advocate in the book.

2. Can you tell ZNet something about writing the book? Where does the content come from? What went into making the book what it is?

Andrej: Staughton came into my life quite unexpectedly. When I decided to move from Yugoslavia I was thinking about writing about some serious stuff that is now popular in academia, such as post-colonial theory or something of the sort. Meeting Staughton destroyed my academic career, and sent me back to a world of serious politics and intellectual engagement with the world outside of the library. Now, somewhat more seriously, my encounter with the fascinating life of Staughton Lynd came at the moment when I was trying to understand why the global movement, the so called anti-globalist movement, is in such a crisis. I thought that a conversation, or, rather, a series of conversations, between a youngish Balkan anarchist who organized for many years in zapatista-inspired direct action global movements, and a seasoned American revolutionary, influenced by Marxism, who has been part of every single major struggle in postwar American history, would be useful to younger activists. I had in mind Students for Democratic Society and the Industrial Workers of the World, both of whom were “reinvented” in recent years. Belgrade and Youngstown and much closer than they appear on the map. The bridge between the two crosses the Lacondonian jungle and bypasses respectable institutions of higher learning.

Staughton: It was basically Andrej’s idea and it was continually he who posed the next question, and the next. The form of the book brings us back to the fact that communication between human beings is basically a conversation. Think of the encounter between the white pacifist and the African American (James Earl Jones) designated to kill him in Matewan, Ignazio Silone’s “Dialogue with Christina” in Bread and Wine, Marechal and Rosenthal in Grand Illusion, the inquiries of Socrates, the parables of Jesus.

3. What are your hopes for Wobblies and Zapatistas? What do you hope it will contribute or achieve politically? Given the effort and aspirations you have for the book, what will you deem to be a success? What would leave you happy about the whole undertaking? What would leave you wondering if it was worth all the time and effort?

Staughton: On the internet this morning (December 20, 2008) one reads of an Iraqi journalist throwing his shoes at President Bush, of Israeli 12th graders refusing to be part of a military occupying the West Bank, of rank-and-file Greek workers occupying the offices of the trade union federation to prevent that bureaucratic organization from suppressing the spontaneous happenings in the streets and local town halls. Such courageous acts need to be understood as something broader than the conscientious refusal of individuals to become part of the pattern of things intended by last-stage capitalism and its creature, the state. That broader resistance began with the “Basta!” (enough!) of the Zapatistas and with their idea of “mandar obediciendo”: those in positions of authority must govern in obedience to what Marcos calls “the below,” that is, us. We are united by affirmation of the “other world” envisioned by protesters at Seattle.

There is a tradition in the United States started by Paine and carried forward by other working-class intellectuals like William Lloyd Garrison, Frederick Douglass, Albert Parsons (in his speech to the jury before being sentenced to death), and Eugene Debs, which says: We are citizens of the world. This, together with the horrors of World War II, is where the UN Declaration of Human Rights originated.

Andrej: We need to declare Marxist vanguardism dead. Enough of colonialism and colonizers, of countries and of factories. We need to discover new ways of doing politics. Accompaniment, as well as an “internationalism of the heart,” this beautiful tradition according to which “my country is the world,” are good guiding concepts for the yet unexplored territory of an innovative revolutionary practice that brings together the historical experience of Bartolomeo Vanzzeti and Subcommandante Marcos, of Rosa Luxemburg and indigenous Bolivia. We hope that our book might be a contribution to a serious discussion about building a movement rooted in the experience of ordinary people, and not the one of a Marxist or anarchist “professoriat,” a movement that refuses to “seize” or be seized by the power of the State, a movement that is horizontal and organized from below.

Back to Staughton Lynd’s Author Page | Back to Andrej Grubacic’s Author Page