By Moira Birss

Fellowship of Reconciliation

November 2014

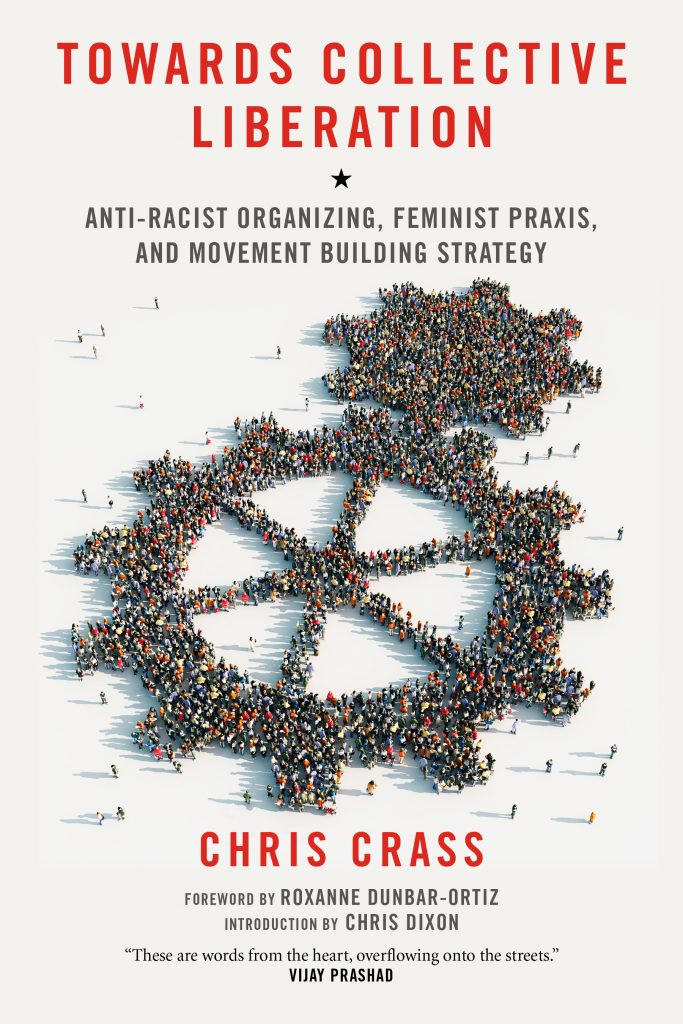

For those of us participating in the struggle to bring about systemic change, but who come from places of gender, racial, or economic privilege, Chris Crass’ Towards Collective Liberation provides a guide, based on the author’s years of experience as an organizer and activist plus interviews with others.

I first met Crass nine years ago, when I had just moved to San Francisco after college and was looking to plug into the activist world there. Our paths only crossed occasionally, but I remember Chris would always engage me in challenging yet gentle conversations about my activism and how I was learning and growing from it.

So it came as no surprise in the book that Chris’ organizing philosophy is based on praxis – and not just with relation to feminism, as the subtitle might suggest. He writes, “I believe in a praxis-based organizing approach in which we develop our analysis and strategy through a process that combines education, practice, reflection, and synthesis, so that our ideas and practices are evolving.” By learning from others, admitting and analyzing our mistakes, and incorporating those lessons back into our work, we as individuals and as collectives transform ourselves and the world. And Chris regularly reminds us of the importance of this constant transformation, because, “If systems of domination are interconnected, then systems of liberation are also interconnected.”

Part of what makes the book so special and accessible is how honest and vulnerable Chris gets about the development of his praxis-based approach – and all the stumbling and mistakes he has made along the way. This particularly struck me in the chapters on feminism and anti-racism. Chris openly admits his personal struggle in recognizing, admitting, and learning to deal with his own sexism and racism. “It was terrifying,” he describes, “because I could handle denouncing patriarchy and calling out other men from time to time, but to be honest about my own sexism, to connect political analysis/practice to my own emotional/psychological process, and to be vulnerable is scary.”

Similarly, he writes about confronting the ways he has benefited from white privilege. But Chris doesn’t just leave us despairing about these systems of oppression; he gives us ideas and tools for transformation. He offers ways white radicals can talk about and work on racism with each other, and dedicates a chapter to tools for men to confront patriarchy.

Chris also charts his experiences in collectives, like Food Not Bombs in San Francisco in the ‘90s. We see the tensions, contradictions, and learning that happened, which can inform future organizing and activism. His interviews at the book’s end serve a similar purpose, providing concrete examples of how activists and collectives have faced such challenges.

In addition to the personal insights, Chris bases his analysis on the long history of radical thinking, with a particular focus on writings by women and people of color. One thing I wished for is an annotated bibliography or reading list of the cited works. After all, we need all the tools we can get for the massive work of collectively transforming ourselves and the world.

But despite the obstacles, Chris leaves us with hope. As he writes: “I have hope because there is a radical vision of love at the heart of our movement and it is growing.”

Moira Birss serves as the Colombia project representative in North America for Peace Brigades International. She previously served for two years on the Fellowship of Reconciliation’s Colombia Peace Presence team (now FOR Peace Presence), and earlier as a FOR Freeman Fellow. She lives in Washington, D.C.