by Lesley Wood

Interface: a journal for and about social movements

Volume 5

November 2013

In her piece, “Love as the Practice of Freedom”, U.S.-based writer bell hooks (1994, 244) argues, “until we are all able to accept the interlocking, interdependent nature of systems of domination and recognize specific ways each system is maintained, we will continue to act in ways that undermine our individual quest for freedom and collective liberation struggle.” In Chris Crass’s new book, he works to show how our movements can understand and counter such internalized and systemic oppressive systems and can move toward these goals of freedom and collective liberation.

The book isn’t a roadmap. Indeed, it is a set of stories and essays of attempts, disasters, and victories of twenty years of organizing in the U.S. within projects including Food not Bombs, the global justice movement, feminist collectives, anti-racist, and queer campaigns. It argues that to organize more effective, revolutionary movements, those of us who are most privileged by the system in terms of our race, class, gender, sexuality or ability need to listen better, to be more humble, and will need to prove ourselves worthy of the trust of organizers from more marginalized communities. But unlike some discussions of the ways that privilege and power operate in movements, Crass’ book doesn’t keep the argument at the level of ethics, but instead grounds it in a reading of history that says that the most transformative, sustainable movements are those that are grounded in the experience of marginalized communities. Crass argues that without keeping this analysis of power and praxis central to our work, organizers that are white, male, cis, straight and able-bodied will be likely to re-enact hierarchical and oppressive relationships, taking us further from the goal of building the relationships necessary for a more democratic, socialist society.

This book is divided into distinct sections, each with a number of pieces ordered roughly chronologically. It begins with a broad agenda–building an anarchist left. The theme of the second section is anti-racist feminist practice, which includes widely read pieces like “Against Patriarchy: Tools for Men to Help Further Feminist Revolution.” This is followed up with a section called; “Because good ideas are not enough: Lessons for vision-based, strategic, liberation organizing praxis,’ with pieces on leadership and the U.S. civil rights movement. The fourth section is described as “collective wisdom” and it brings together lessons from five different and diverse anti-racist organizing projects through interviews and essays.

While a few of the pieces in the collection were previously distributed on the Colors of Resistance listserv and website, and through a collection of essays put out by Kersplebedeb distribution, bringing them together and framing them so cogently gives them additional power. It is Crass’ book, but he is at pains to emphasize that both the book and the organizing behind it are part of an ongoing collective effort to make more strategic, transformative movements.

The first pages of the book are jam packed with a who’s who of endorsements by some of today’s most skilled organizers in the U.S., and the book itself contains many voices, including a forward by Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, author of Red Dirt Woman and The Great Sioux Nation: Oral History of the Sioux-United States Treaty of l868; an introduction by Chris Dixon, author of a forthcoming book on anarchist organizers, and the interviews with five different anti-racist organizing projects.

Personally, this is a book I’ve waited a long time for. Crass is a white U.S. anarchist who became politically active in the 1990s via suburban punk rock.The book articulates the evolution of an anarchist politics that some of us came to in the 1990s and 2000s, out of a recognition that hierarchy couldn’t be reduced to race, class, gender and sexuality. It is a politics that took into account the idea that the personal was political, and the feeling that large, ritualized protests were not creating a more just and fulfilling world. While such anarchist work is widespread in a wide range of contemporary organizing, including immigrant rights, Occupy, police brutality, and student movements–it is more visible in workshops than in publications. Crass puts this ‘small a’ anarchist approach into historical context.

This is not just a book for anarchists, and indeed many anarchists won’t see themselves within it. But it is a book for those interested in the challenges and gifts of grassroots organizing, whether they see themselves as communists, anarchists, revolutionary sovereigntists, feminists, queer activists–or some combination of the above. Indeed, he’s been certified by some of the most powerful grassroots organizers in the U.S. today.

This book is meant for those engaged in, wanting to be engaged in, or burned out from being engaged in, deep, transformative social justice work. It should be read and discussed by organizers interested in building multi-racial, anti-capitalist, feminist movements. It is written from the perspective of white organizers in a U.S. context, and will be particularly relatable for audiences sharing that space and identity. However, it offers accessible, strategic thinking about the intersection of different forms of inequality and the dynamics of alliance building that should offer insight to those in other contexts and positions.

Rich with stories that will make you laugh and groan, it is full of solid, earnest, loving advice that will push you to think more strategically and patiently about the work that social justice requires. Unlike some discussions of organizing, Crass doesn’t suggest that this work will be easy. He recounts the stories of awkward meetings, angry confrontations and bad strategy. He clearly shows us why challenging power inequalities within our organizing can be far more emotionally draining than occupying a government office or marching on Washington. Nonetheless, Crass concludes with a hopeful essay entitled, “We can do this.” He doesn’t want our movements to get stuck, to get depressed and for our activists to eat each other, and the next generation of organizers, alive.

He tackles the tendency for organizers, activists and

radical academics to spend much of our time critiquing our movements and

our politics. Crass rightly points out that while critique is a crucial

part of rethinking and rebuilding existing practices, the trap of

right/wrong, solid/fucked up can trap us, steal our energy, and stop us

from thinking creatively and strategically for the long haul. Instead he

suggests that in order to be strategic, and to keep our momentum up, we

need to combine critical reflexivity with a focus on the opportunities

and assets we have, and work to build a just world.

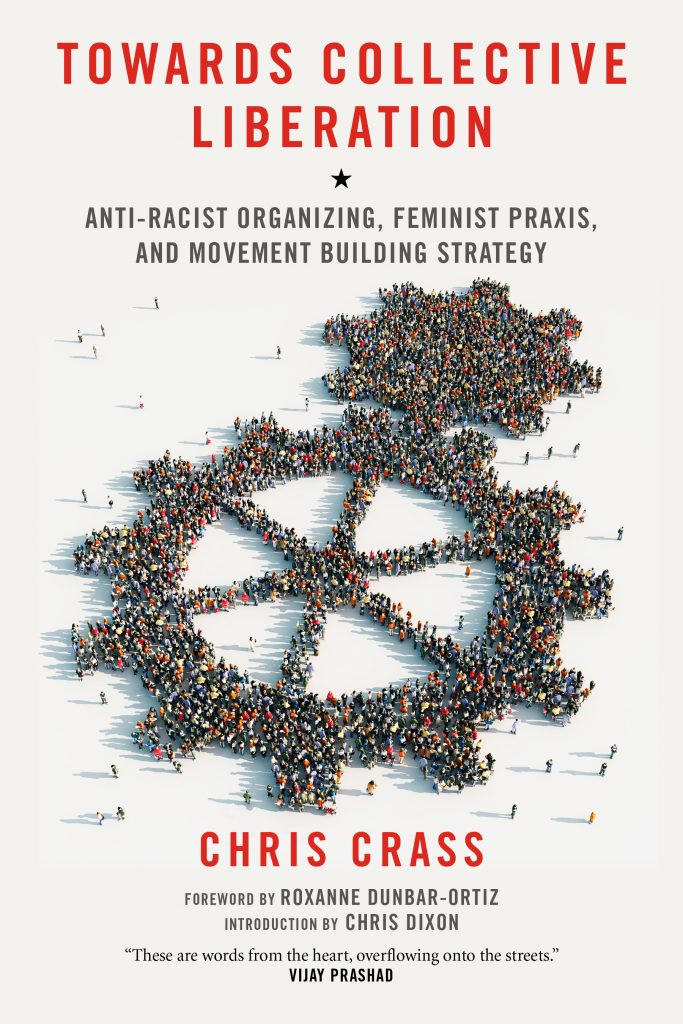

Towards Collective Liberation

is the sort of book you want to hand to your comrades and friends, read

passages from, and head into the streets. With a book like this, it

feels like yes indeed, we can do this.

References

Hooks, bell. 1994. Outlaw Culture: Resisting Representations.

New York City: Routledge.

About the review author Lesley Wood is an organizer and scholar in Toronto, Canada.