By Erik Wecks

Wired.com

May 8, 2012

Does Cory Doctorow Think The Matrix Got It Wrong?

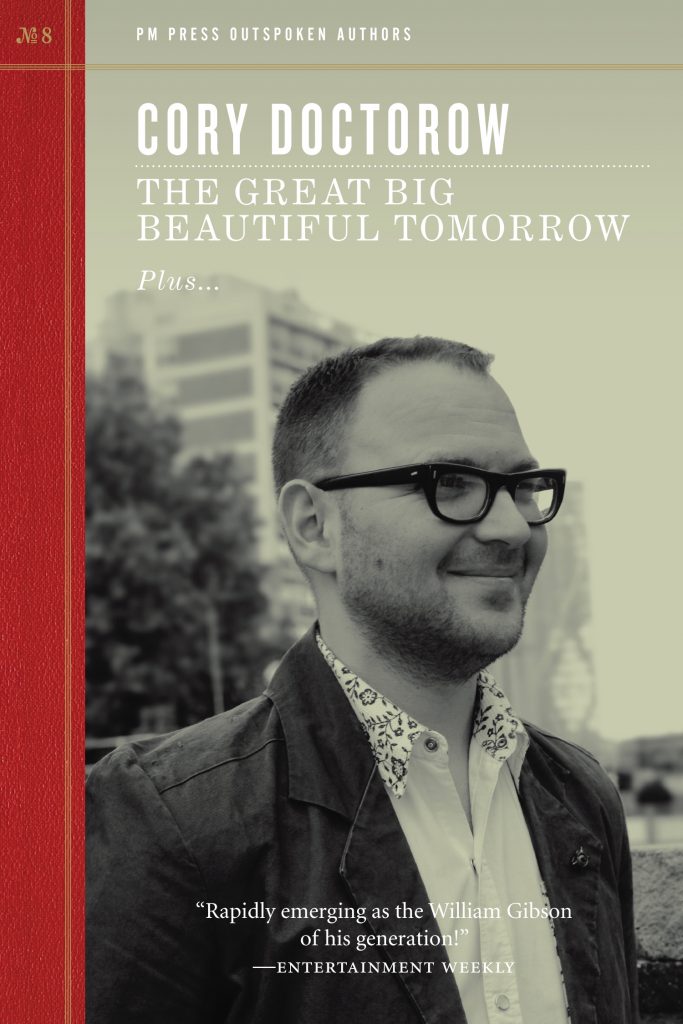

Cory Doctorow’s The Great Big Beautiful Tomorrow is a little book divided into three parts. The first part is a novella by Doctorow. The second is a transcript of his address to the 2010 World Science Fiction Convention titled “Creativity vs. Copyright” in which Doctorow argues that DRM technologies are bad for content creators. The final section is a wonderful interview with Doctorow on his thinking and the writing process.

At first it may not seem that these three different pieces of writing would fit together very well in a single volume. A closer reading, though, shows they provide a surprisingly coherent view into Doctorow’s thought and work. The address and the interview are more easily understood, but without a careful reading the novella can seem to contradict them. Placing it in context with the other two pieces will require some spoilers. If you are interested in reading the novella before you finish this review, you can read an electronic copy from the publisher and then come back. (You can also purchase a paperback copy on Amazon. The publisher’s site is the only way to get a digital version.) It should only take you a couple of hours to read the novella. Just a note, as the back cover of the book states the story revolves around “a transhuman teenager in a toxic post-Disney dystopia, who is forced to choose between immortality and sex.” So there is one explicit sex scene in the book. This isn’t part of Doctorow’s YA fiction. It is for adults. Warning: there are spoilers ahead.

As the cover blurb indicates, the hero, Jimmy Yensid (spell that backwards), is a trans-human child created to be nearly immortal. He will die someday, but that is in a future in which it is said you wouldn’t recognize the continents because of the tectonic drift. Jimmy and his father live in a post-technology world where any desired change is possible. At one point in the book Jimmy Yensid says that his world has “outgrown progress” and what was left was only “change.” Changes either became popular or they fade away. Yet from Jimmy’s perspective change no longer brings with it growth. Jimmy and his father long for a time when the growth from technology was clearer, linear and easy. The angst created by this post technology environment has caused Jimmy’s father to reject both change and progress. He has spent his life trying to preserve Detroit, the last remaining American city, from Wumpuses. Wumpuses are robots which eat inorganic matter and turn it back into arable soil. The two of them live there alone, mostly isolated from other human beings. Jimmy’s father’s prize possession is the Carousel of Progress created by Walt Disney for the 1964 New York World’s Fair which he has painstakingly restored. Early in the story, Jimmy’s father disappears in an attack on Detroit by eco-terrorists. Jimmy escapes and spends the next couple of decades of his life preserving the carousel and giving out rides to a group of cult members who share an emotional consciousness.

The multi-layered ironies in Doctorow’s writing are rich and wonderful particularly when it comes to Jimmy’s father. Here is a man who has dedicated his life to preserving an artifact which declares that humans should embrace change and accept progress. Yet even the ride itself is a kind of irony. It is a carousel which spins in a circle doing the same thing over and over again. It never moves and it never changes, even as it speaks about the wonders of the future, a future which is long past. Jimmy’s father is certainly not afraid of technology. After all he built a child who for all intents and purposes is immortal. However Jimmy’s father only uses technology in the service of preservation. Before his father disappears, change only happens in Jimmy’s world in order to preserve the existing order. This is truly a world in which the vision of Walt Disney runs in reverse. Technology is used to preserve the status quo, to entomb the present in the past, rather than to bring humans into The Great Big Beautiful Tomorrow.

The Carousel of Progress. Credit: Wikimedia CC

My favorite exposition of this irony comes from Jimmy himself who spends much of the story fulfilling his father’s vision. He criticizes his only friend Lacey for creating a transgenic goat that gives spider silk rather than milk. “You think she enjoys giving silk? Somewhere in her head she knows she is supposed to be giving milk.” Goats should be left alone the way nature intended them, argues Jimmy. The rich irony of those words coming from the mouth of the first trans-human are just wonderful. Yet at the time he says it Jimmy doesn’t even perceive the irony. He is technology used to preserve the past. He has no vision for the future. His existence is merely a “change,” not “progress.”

This scene is about as sharp a scalpel as an author can create. But this only becomes apparent if the reader understands that trans-genetic goats who give spider silk protein in their milk already exist. (Watch New York Times reporter David Pogue’s Nova series Making Stuff to see these goats in action.) The reader is forced by Doctorow to ask how they view technology. Do we see technology as a means to preserve the status quo or as a means to better human existence, as progress? Even more than that, Doctorow challenges us to recognize that we are products of technology ourselves. We cannot oppose progress through technology without irony, because we are products of medical science, information technology and the industrial revolution. (In some sense, I think Doctorow seems to be saying that we are already trans-human.)

According to Doctorow, to use technology to preserve the status quo is to deny something about what we are as human beings and this powerful observation is the thread which ties the novella to the other essays in the book and to the rest of Doctorow’s work. It explains his distaste for DRM technologies—the subject of the address in the book—and guides all his fiction —the subject of the interview which closes the book.

Throughout his life Jimmy Yensid remains unhappy. Jimmy eventually tires of his body’s glacial pace of change. The catalyst for his decision to alter his future is a run-in with the only girl—now woman—for whom he has felt sexual attraction. Lacey returns mid-way through the book as a thirty-something woman of the world. Jimmy remains an early pubescent forever trapped in the body his father made for him. Their love affair acts as a catalyst for Jimmy to seek a way to grow older more quickly so that he can be with Lacey. No more will Jimmy seek to use technology to stop progress.

Doctorow’s ending to Jimmy’s hero’s journey is fascinating. For the last third of the story Jimmy fights off clones himself who want to “mind rape” him and place his consciousness in a computer. After a great chase scene, Jimmy is defeated and ironically achieves his hero’s victory. Inside this Matrixesque world Jimmy finds both his girl and his father waiting for him. Jimmy and Lacey are able to age together through the power of technology and are free to love each other as they have desired. While not perfect, their existence is portrayed as idyllic. Jimmy only finds peace with himself and the life he desires when he embraces the possibilities and progress technology offers, when he becomes literally part of the machine.

What makes Doctorow’s story so unique is that in almost every science fiction story meat-space is privileged over cyber-space. The hero wins when they successfully resist technology and establish their humanity as an opposing force against the tyranny of the machine. Doctorow and other techno-positive thinkers like him argue forcefully that such thinking can only lead to dystopia and suffering. In a world of ever-quickening technological upheaval the question remains important for us: Change or Progress?