By Jo Walton

Tor.com

April 22nd, 2009

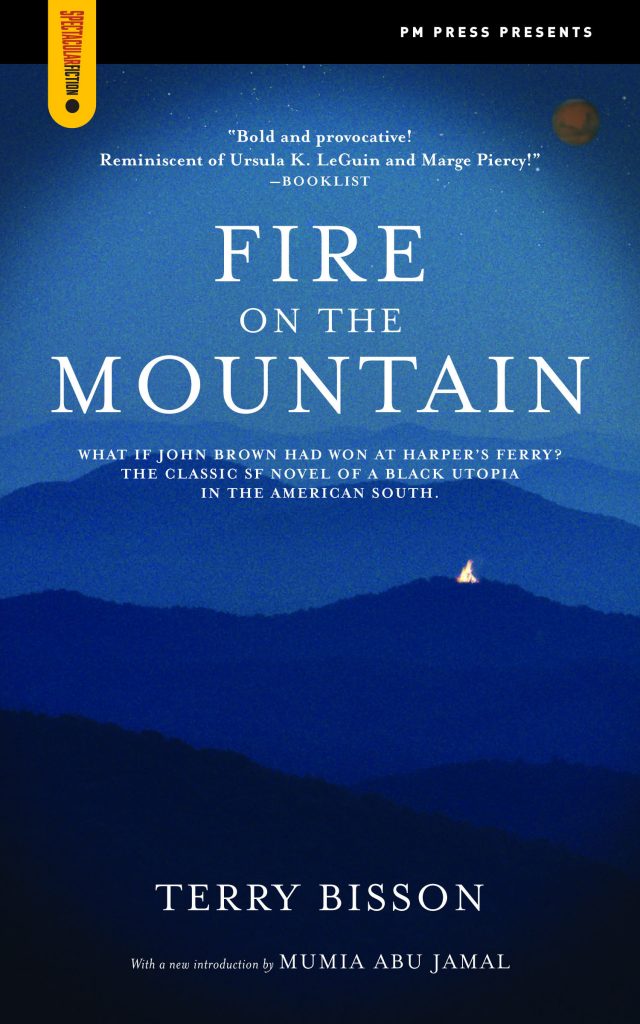

After reading Kindred, I wanted to read something where the slaves were freed, and not just freed a bit, but freed a lot. So that would be Terry Bisson’s Fire on the Mountain (1988). It’s an alternate history, and an alternate US Civil War where John Brown’s raid on Harper’s Ferry is successful. The book is set a hundred years later in 1959 on the eve of the first manned Mars landing, but it also contains letters and a diary from 1859.

Terry Bisson is one of those brilliant writers who is inexplicably uncommercial. He has the gift of writing things that make me miss my stop on the metro because I’m so absorbed, but I almost never meet anyone who reads him. My very favourite book of his is Talking Man, an American fantasy, which I will no doubt talk about here in due course. A Fire on the Mountain runs it a close second. It got wonderful reviews—they’re all over this Ace paperback I bought new in 1990. His short work wins awards, and I’ll buy SF magazines if he has a story in them. I think he’s one of the best living stylists. But all he has in print are a three admittedly excellent collections.

It’s hard to write stories in Utopia, because by definition story-type things don’t happen. In Fire on the Mountain Bisson

makes it work by the method Delany and Kim Stanley Robinson have also

used, of having a central character who isn’t happy. (You can convey

dystopias well by the opposite method of having characters who are

perfectly cheerful about them. But dystopias are easier anyway.)

Yasmin’s husband died on the first Mars fly-by mission five years ago.

He’s a hero to the world, but she can’t get over not having his body to

bury. The new Mars mission, which is taking his name on a plaque, is

breaking her heart every time she hears about it on the news. She’s an

archaeologist who has been recently working at Olduvai. She’s now going

to Harper’s Ferry with her daughter Harriet to take her

great-grandfather’s diary to the museum there. The book alternates

between her trip, her great-grandfather’s diary of how he escaped

slavery and joined the rebellion, and the 1859 letters of a white

liberal abolitionist.

This is, like all Bisson’s work, a very

American book. It’s not just the history, it’s the wonderful sense of

place. I found myself thinking of it when I went on the Capitol Limited

train down through Harper’s Ferry last summer, the geography of the

novel informed the geography out of the train window. At one point I

realised I’d just crossed the bridge that is destroyed in the book—but

which wasn’t in real life. That was the turning point of history—in

Bisson’s novel, Tubman was with Brown and they burned the bridge, and

everything was different afterwards. In Bisson’s 1959, the south, Nova

Africa, with it’s N’African inhabitants, black and white, and the north,

the United Socialist States of America, are at peace, the border seems a

lot like the way the border between the US and Canada used to be.

(Speaking of Canada, Quebec is mentioned separately from Canada and must

have gained independence somehow, or maybe Confederation happened

differently. Unsurprisingly, Bisson doesn’t go into detail.)

I like

the characters, all of them, the 1859 and the 1959 ones. The minor

characters are done very expressively with just a little description

going a long way:

Harriet was at the Center, Pearl said, working on Sunday, was that what socialism was all about, come on in? Not that Harriet would ever consider going to church, she was like her Daddy that way, God Rest His Soul, sit down. This was the week for the Mars landing, and Pearl found it hard to listen to on the radio until they had their feet on the ground, if ground was what they called it there, even though she wished them well and prayed for them every night. God didn’t care what planet you were on, have some iced tea? Or even if you weren’t on one at all. Sugar? So Pearl hoped Yasmin didn’t mind if the radio was off.

and the book’s style moves seamlessly from that kind of thing to:

Dear Emily, I am writing to tell you that my plans changed, I went to Bethel Church last night and saw the great Frederick Douglass. Instead of a funeral, I attended a Birth. Instead of a rain of tears, the Thunder of Righteousness.

I like the way the history seems to fit together without all being explained. I like the shoes from space that learn your feet, and the way they are thematic all the way through. I like the way the people in 1959 have their own lives and don’t think about the historical past any more than people really do, despite what Abraham thought when he wrote for his great-grandson, not guessing it might be a great-grand-daughter. I like the buffalo having right of way across highways and causing occasional delays. I like the coinage N’African, and I like that almost all the characters in the book are black but nobody makes any fuss about it. (They didn’t put any of them on the cover, though.)

There’s one heavyhanded moment, when a white supremacist (the descendant of the white abolitionist doctor) gives Yasmin a copy of a 1920s alternate history “John Brown’s Body,” a book describing our world. They don’t think much of it, and you can understand why. Their world is socialist, green, more technologically advanced—it’s 1959 and they have space manufacturing and a Mars mission, as well as airships (of course!) and green cars—and still has herds of buffalo and nations of first nations people. Texas and California rejoined Mexico. Ireland won independence in 1885. It’s been a struggle, and it feels complicated, like history, but not many people would prefer the racism, class problems and injustice of our world. Yet it isn’t preachy, except for that one moment.

I’ve heard it said that the US obsession with their Civil War, and the large number of alternate histories featuring it as a turning point, arises out of a desire to have slavery back. I think even the South Triumphant novels are more often Awful Warnings than slaver panegyrics, and A Fire on the Mountain puts the whole thing in a different light. People want to do the Civil War again and get it right this time. The book may be a little utopian, a little naive, but it’s a beautifully written story about a nicer world, where, in the background, people are landing on Mars. In 1959.