By Sam J. Miller

GuysLitWire

August 13th, 2014

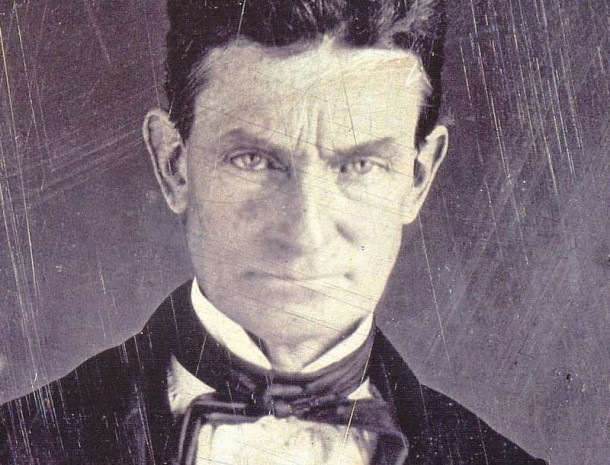

Maybe you remember John Brown from your history class. An abolitionist, he believed that peaceful reform of slavery was impossible, and only a violent disruption of the slaveholding status quo would end this massive, brutal injustice. In 1859 he attempted to start a slave revolt by seizing the US arsenal at Harper’s Ferry in Virginia, but the assault went wrong and he and his comrades were caught and executed for treason.

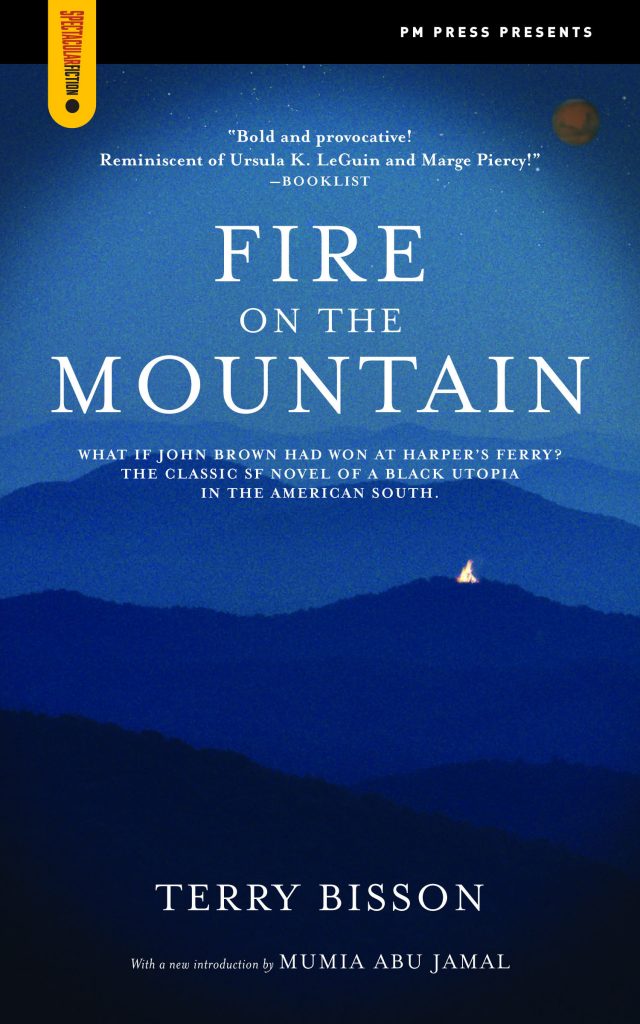

Terry Bisson’s Fire on the Mountain is an alternate history that asks the question – what if the assault had succeeded? What if instead of a civil war started by slaveholders who wanted to continue exploiting human beings, America had a revolution started by people who believed that all human beings should be free? In real life, John Brown worked closely with Harriet Tubman, and many scholars believe that if she hadn’t been prevented by illness from traveling south to help him plan the attack, he would have succeeded. Fire on the Mountain takes a simple change – she didn’t get sick, she helped the rebels, the attack was successful and started a revolution – and extrapolates a whole complicated marvelous utopian future from that. It opens 100 years later, as the prosperous state of Nova Africa is about to put a man on Mars, and pieces together the history through letters and testimonials.

Bisson’s John Brown is no white savior, coming to rescue helpless people of color. Harriet Tubman is as important a force of liberation, and the book is full of strong compelling characters (including slaves) who make active decisions that drive the plot forward. Nor does Bisson skimp on the nuanced details of how, exactly, the Harper’s Ferry raid leads to such massive historic changes. It’s also remarkable for how, without seeming boring or didactic or ideological, it captures the diverse opinions of abolitionists (ranging from people who oppose slavery but refuse to DO anything about it, to people who take up arms and are willing to kill and die for the cause).

Alternate history is like candy-coated medicine. We love it, because it’s fun and wacky and imaginative and

isn’t bound by some of the things that can make real history range from

boring (like memorizing dates) to upsetting (like the fact that

history is full of oppression and suffering and massacres and

exploitation).

But under the candy shell of crazy what-ifs and shiny rocketships, alternate history is history.

It gives us a new and deeper perspective and insight into history as a

real thing, a vibrant and compelling story, as opposed to numbers in a

book. For example: Scott Westerfeld’s “Leviathan” trilogy takes place

in an alternate-history World War One where 19th century scientific

advances filled the world up with giant robots and flying whales… and

yet it brings the spirit of the actual period to life, giving young

readers a sense of the issues at play in that conflict.

Fire on the Mountain is

a brilliant book, deeply moving for the strength of its imagination

and the warm-hearted generosity of its spirit, for the audacity of an

author who dares to propose a history less horrible. I suspect it would

work as well on a young man who is excited about issues of history

& race & activism, as it would on a guy who doesn’t care about

any of that, but likes a good science fiction story.